Devvy

Donor

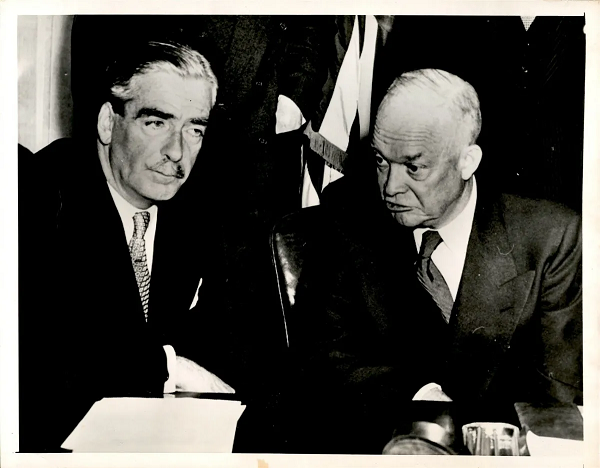

Anthony Eden

Conservative Premiership, 1953-1960, won election 1955

Eden and Eisenhower oversaw a souring of the US-British relationship following the Second World War.

The United Kingdom today owes a significant part of it's heritage to the efforts of Anthony Eden. Taking over from Churchill as party leader and Prime Minister in 1953 following Churchill's rapidly failing health (and following his own successful surgery that year), Eden had to tackle a rapidly evolving global stage with the British Empire in decline, the ascendency of the United States and Soviet Union and a divided Europe.

In 1956, Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal - as legally allowed, if controversial - and set in to play a series of events for the United Kingdom. This led to an almost quick-fire set of international discussion on how to handle it; for France and Britain (although for slightly different reasons) the Suez Canal was a critical piece of global infrastructure, allowing freight to transit between Asia/Pacific and Europe far quicker then circumventing the entire continent of Africa. Eden was incensed by the Egyptian move, despite the fact that the 1954 Treaty required Britain to draw down it's troops in the Suez Canal Zone anyhow. Franco-Israeli desires to hit Nasser hard and quickly were also therefore shared by Eden in Britain, who saw Nasser as potentially the next Hitler, but ideas of Britain taking action against Nasser were quickly stymied by American opposition. The US was deeply involved in the British economy, and could make or break the country in the 1950s, and discussions between Eden and Eisenhower highlighted the deep opposition of the Americans to any action in Egypt which could jeopardise their attempts to keep Egypt out of the Soviet camp, and avoid any notion of backing a colonialist power move. Despite the United Kingdom awarding India and Pakistan independence in the late 1940s, it was still a heavily empire-led nation at the time - an increasing contradiction between the world's foremost imperial power and the world's foremost presidential republic at the time. This set off a chain of events leading to Britain's "Allied Approaches" foreign policy strategy to the United States, recognising it as a crucial ally, but a nation who Britain would routinely have different strategies, aims and processes to even if pursuing the same end goal.

Although acknowledging Egypt's actions to nationalise the canal, as long as the flow of traffic was not interfered with and the charging process remained reasonable, Eden was wary of Nasser. In to this mix were the Malta integration talks, headed by the Maltese Dom Mintoff, who was frequently unpredictable. Much of the discussions were financial & economic in subject; Mintoff's desire for economic parity with the UK met with British hesitance over writing a blank cheque every year to Malta. Social programmes would be expensive to fund in Malta due to demographics, whilst the tax earned would be far smaller. However, in light of nationalisation of the Suez Canal, as well as rejection of the "international status" of the Suez (implicit in efforts to cut Israel off), there was a greater requirement for British security in the Mediterranean, and towards Egypt. The British, despite not taking part directly, did quietly allow the French to use British air bases in Cyprus in transit.

Outline agreement with Malta was therefore found in late 1956, and the Maltese national referendum on the matter backed the proposal; just roughly 75% of voters did so to join the UK. In terms of the electorate, just over 51% voted to join the UK, 15% voted against integration, and just over 34% didn't vote - either not caring or abstaining. Integration would see Malta become part of the UK along similar lines to Northern Ireland; a full part of the country, electing MPs to Westminster and a local "Maltese Assembly" taking care of local affairs. In light of the experiences of Northern Ireland, several powers were reserved to Westminster, primarily around the economy given the expected expense of Maltese integration. The Maltese pound would be technically withdrawn and replaced by UK Pound Sterling directly, although an sub-agreement between the Maltese and British Government enabled a new "Royal Bank of Malta" to print their own bank notes under the same terms as the Scottish and Northern Irish banks. In lieu of this and the possible expense of Malta, British Rail saw it's requested budget for modernisation slashed, forcing it to concentrate on a limited amount of new traction and electrification, as well as further closures of unproductive routes, whilst reconsideration of British air force projects brought about a reconsideration of future interceptor aircraft to utilising Avro for their connections with the Canadian Arrow project and cost savings. Reductions in the air force industry had been long expected due to the overly large amount of small manufacturers, but the choice for Avro put many smaller manufacturers out of business or forced to merge.

Although Eden had been forced to not take military action in Egypt regarding the Suez Canal, the affair had laid clear the separate interests of the United States and the United Kingdom, the former of whom had made abundantly clear it's rejection of any military action and hinted at counter-action if Britain did so. The failure to back the United Kingdom, in the view of the British Government, was perceived as yet another split following the failure to share the fruits of nuclear weapons research, taking the relationship between the wartime "closest allies" to a new low, despite the public image as close allies within the NATO alliance.

The events of the Suez, now known as the Suez Affair in Britain, highlighted the requirement to be prepared for conflict either in the Atlantic or in the Mediterranean as needed. This would see the imperial presence East of Suez maintained to secure use of the canal and force it open if needed, as well as maintaining a US-friendly but more independent international stance. A home base in Malta, outright owned and operated by the Royal Navy would tie in with this objective well, whilst also sitting not far from Egypt where a conflict could quickly arise over transit rights in the canal. This set of a series of steps which would transform the British armed forces over time, with a greater focus on an independent power projecting force and dovetailing in to NATO where Eden retained Britain's role within the integrated command despite the French partial withdrawal - remaining in the core of NATO continued to be perceived as essential for the defence of Europe and implicitly Britain.

And so in 1959, Malta acceded to the United Kingdom - then a historic event, and unparalleled since 1801 when Ireland was merged in to the United Kingdom alongside Great Britain for better or worse. Over the next 15 years, Malta would be gradually invested in and economic parity targeted with at least the lower UK regions. The 1958 Act of Union, passed in both Westminster and Valetta merged Malta in to the United Kingdom, although for the first time since the English-Welsh legal union in the 16th century, the flag would remain unchanged. Malta was assigned three constituencies for the sake of elections to Westminster; Gozo, Malta West and Valletta, and a 12 year transition period (having begun in 1958 with the Acts of Union) would work to economically integrate Malta in to the United Kingdom and achieve rough equivalence with Great Britain (in terms of purchasing power parity).

The 1960 election would be the first to elect 3 MPs from the Maltese constituencies. Eden had recognised early on that Malta would likely be Labour leaning, and the alliance of the Maltese Labour Party with the UK-wide Labour party did little to temper this. The electoral fight was for Eden's successor, Macmillan, to conduct however, and the booming economy in the late 1950s led the electorate to return the Conservative Government - but with a far reduced majority, with 3 Labour MPs elected from all three Maltese constituencies as expected. Harold Macmillan duly retained the role of Prime Minister, but with a very slim majority in Parliament, an unwelcome hark back to Attlee's Premiership following the 1950 election.

------------

Notes:

Welcome back to a hopefully more thorough telling of the UK overseas regions timeline I did a few years ago, with more detail in it and consideration of other butterflies. What started out for me as a rewrite of the Overseas Regions timeline I did, spun out quickly in to the UK pursuing a somewhat more independent foreign policy aim and becoming increasingly close to France to replace it's US Special Relationship.

The PoD is here is Eden not having botched surgery; here he has had successful surgery which hasn't left him addicted to a cocktail of drugs and the inevitable irritability. He's been able to approach Suez with a better mindset, and this time correctly read the US feeling over potential Suez action. The Israeli invasion has still gone ahead with French support; an Israeli-Nasser showdown was on the cards anyway, but this time it's with tacit British support rather then explicit support. This has led to the integration of Malta, as a close major naval base for projecting power towards the Suez and keeping the canal open for British interests, and a far more "Frenchy" - or in the end European - United Kingdom is on the cards.

Conservative Premiership, 1953-1960, won election 1955

Eden and Eisenhower oversaw a souring of the US-British relationship following the Second World War.

The United Kingdom today owes a significant part of it's heritage to the efforts of Anthony Eden. Taking over from Churchill as party leader and Prime Minister in 1953 following Churchill's rapidly failing health (and following his own successful surgery that year), Eden had to tackle a rapidly evolving global stage with the British Empire in decline, the ascendency of the United States and Soviet Union and a divided Europe.

In 1956, Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal - as legally allowed, if controversial - and set in to play a series of events for the United Kingdom. This led to an almost quick-fire set of international discussion on how to handle it; for France and Britain (although for slightly different reasons) the Suez Canal was a critical piece of global infrastructure, allowing freight to transit between Asia/Pacific and Europe far quicker then circumventing the entire continent of Africa. Eden was incensed by the Egyptian move, despite the fact that the 1954 Treaty required Britain to draw down it's troops in the Suez Canal Zone anyhow. Franco-Israeli desires to hit Nasser hard and quickly were also therefore shared by Eden in Britain, who saw Nasser as potentially the next Hitler, but ideas of Britain taking action against Nasser were quickly stymied by American opposition. The US was deeply involved in the British economy, and could make or break the country in the 1950s, and discussions between Eden and Eisenhower highlighted the deep opposition of the Americans to any action in Egypt which could jeopardise their attempts to keep Egypt out of the Soviet camp, and avoid any notion of backing a colonialist power move. Despite the United Kingdom awarding India and Pakistan independence in the late 1940s, it was still a heavily empire-led nation at the time - an increasing contradiction between the world's foremost imperial power and the world's foremost presidential republic at the time. This set off a chain of events leading to Britain's "Allied Approaches" foreign policy strategy to the United States, recognising it as a crucial ally, but a nation who Britain would routinely have different strategies, aims and processes to even if pursuing the same end goal.

Although acknowledging Egypt's actions to nationalise the canal, as long as the flow of traffic was not interfered with and the charging process remained reasonable, Eden was wary of Nasser. In to this mix were the Malta integration talks, headed by the Maltese Dom Mintoff, who was frequently unpredictable. Much of the discussions were financial & economic in subject; Mintoff's desire for economic parity with the UK met with British hesitance over writing a blank cheque every year to Malta. Social programmes would be expensive to fund in Malta due to demographics, whilst the tax earned would be far smaller. However, in light of nationalisation of the Suez Canal, as well as rejection of the "international status" of the Suez (implicit in efforts to cut Israel off), there was a greater requirement for British security in the Mediterranean, and towards Egypt. The British, despite not taking part directly, did quietly allow the French to use British air bases in Cyprus in transit.

Outline agreement with Malta was therefore found in late 1956, and the Maltese national referendum on the matter backed the proposal; just roughly 75% of voters did so to join the UK. In terms of the electorate, just over 51% voted to join the UK, 15% voted against integration, and just over 34% didn't vote - either not caring or abstaining. Integration would see Malta become part of the UK along similar lines to Northern Ireland; a full part of the country, electing MPs to Westminster and a local "Maltese Assembly" taking care of local affairs. In light of the experiences of Northern Ireland, several powers were reserved to Westminster, primarily around the economy given the expected expense of Maltese integration. The Maltese pound would be technically withdrawn and replaced by UK Pound Sterling directly, although an sub-agreement between the Maltese and British Government enabled a new "Royal Bank of Malta" to print their own bank notes under the same terms as the Scottish and Northern Irish banks. In lieu of this and the possible expense of Malta, British Rail saw it's requested budget for modernisation slashed, forcing it to concentrate on a limited amount of new traction and electrification, as well as further closures of unproductive routes, whilst reconsideration of British air force projects brought about a reconsideration of future interceptor aircraft to utilising Avro for their connections with the Canadian Arrow project and cost savings. Reductions in the air force industry had been long expected due to the overly large amount of small manufacturers, but the choice for Avro put many smaller manufacturers out of business or forced to merge.

Although Eden had been forced to not take military action in Egypt regarding the Suez Canal, the affair had laid clear the separate interests of the United States and the United Kingdom, the former of whom had made abundantly clear it's rejection of any military action and hinted at counter-action if Britain did so. The failure to back the United Kingdom, in the view of the British Government, was perceived as yet another split following the failure to share the fruits of nuclear weapons research, taking the relationship between the wartime "closest allies" to a new low, despite the public image as close allies within the NATO alliance.

The events of the Suez, now known as the Suez Affair in Britain, highlighted the requirement to be prepared for conflict either in the Atlantic or in the Mediterranean as needed. This would see the imperial presence East of Suez maintained to secure use of the canal and force it open if needed, as well as maintaining a US-friendly but more independent international stance. A home base in Malta, outright owned and operated by the Royal Navy would tie in with this objective well, whilst also sitting not far from Egypt where a conflict could quickly arise over transit rights in the canal. This set of a series of steps which would transform the British armed forces over time, with a greater focus on an independent power projecting force and dovetailing in to NATO where Eden retained Britain's role within the integrated command despite the French partial withdrawal - remaining in the core of NATO continued to be perceived as essential for the defence of Europe and implicitly Britain.

And so in 1959, Malta acceded to the United Kingdom - then a historic event, and unparalleled since 1801 when Ireland was merged in to the United Kingdom alongside Great Britain for better or worse. Over the next 15 years, Malta would be gradually invested in and economic parity targeted with at least the lower UK regions. The 1958 Act of Union, passed in both Westminster and Valetta merged Malta in to the United Kingdom, although for the first time since the English-Welsh legal union in the 16th century, the flag would remain unchanged. Malta was assigned three constituencies for the sake of elections to Westminster; Gozo, Malta West and Valletta, and a 12 year transition period (having begun in 1958 with the Acts of Union) would work to economically integrate Malta in to the United Kingdom and achieve rough equivalence with Great Britain (in terms of purchasing power parity).

The 1960 election would be the first to elect 3 MPs from the Maltese constituencies. Eden had recognised early on that Malta would likely be Labour leaning, and the alliance of the Maltese Labour Party with the UK-wide Labour party did little to temper this. The electoral fight was for Eden's successor, Macmillan, to conduct however, and the booming economy in the late 1950s led the electorate to return the Conservative Government - but with a far reduced majority, with 3 Labour MPs elected from all three Maltese constituencies as expected. Harold Macmillan duly retained the role of Prime Minister, but with a very slim majority in Parliament, an unwelcome hark back to Attlee's Premiership following the 1950 election.

------------

Notes:

Welcome back to a hopefully more thorough telling of the UK overseas regions timeline I did a few years ago, with more detail in it and consideration of other butterflies. What started out for me as a rewrite of the Overseas Regions timeline I did, spun out quickly in to the UK pursuing a somewhat more independent foreign policy aim and becoming increasingly close to France to replace it's US Special Relationship.

The PoD is here is Eden not having botched surgery; here he has had successful surgery which hasn't left him addicted to a cocktail of drugs and the inevitable irritability. He's been able to approach Suez with a better mindset, and this time correctly read the US feeling over potential Suez action. The Israeli invasion has still gone ahead with French support; an Israeli-Nasser showdown was on the cards anyway, but this time it's with tacit British support rather then explicit support. This has led to the integration of Malta, as a close major naval base for projecting power towards the Suez and keeping the canal open for British interests, and a far more "Frenchy" - or in the end European - United Kingdom is on the cards.