I know this is a Greek centric alternate history but I gotta admit to a bias/preference for France , I also would like to give a large thanks for the happier fate you’ve given Napoleon II SO FAR…Thank you!

The next 12ish chapters will focus mainly on Greece and the Balkans, but after that I fully intend to cover what has been happening in other parts of the world since we last saw them

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Pride Goes Before a Fall: A Revolutionary Greece Timeline

- Thread starter Earl Marshal

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan LeagueI know this is a Greek centric alternate history but I gotta admit to a bias/preference for France , I also would like to give a large thanks for the happier fate you’ve given Napoleon II SO FAR…

And I, for one, am very interested in seeing Geoge Washington Adams dealing with the American Civil War (having three generations of Adams presidents, and one of them being the one who - hopefully - saves the Union, is just too cool!). But I also don't want this to drift into Amero-centrism either.

To be honest, I did consider abandoning this timeline and either redoing it from the beginning or starting on my next timeline which I've been teasing here and there for a while now. Ultimately I decided to continue this since I'm finally past what I consider to be the most difficult part of the timeline and I owe you all a definitive ending to this story.I’m late to the party but I’ll add my voice to those welcoming you back. I was worried you’d decided to drop the timeline so it was a welcome surprise to see the notification. I don’t have much to say about the last chapter as it’s obviously laying the groundwork for this government I the coming chapters. It was a fun read though.

I agree wholeheartedly. Napoleon II's life was rather unfortunate in OTL and whilst TTL's definitely won't be perfect for him, it will still be much better.I know this is a Greek centric alternate history but I gotta admit to a bias/preference for France , I also would like to give a large thanks for the happier fate you’ve given Napoleon II SO FAR…

Wait who said anything about him saving the Union!And I, for one, am very interested in seeing Geoge Washington Adams dealing with the American Civil War (having three generations of Adams presidents, and one of them being the one who - hopefully - saves the Union, is just too cool!). But I also don't want this to drift into Amero-centrism either.

Thanks! Glad to be back! I'll have the next update up a little later today.Happy to see you back and to hear a dozen updates await!

Hearing this is slightly disheartening but unsurprising. I've been hit by month long writers block before, or life just getting too busy, and it takes a lot to go back to a project that has been on the back burner.To be honest, I did consider abandoning this timeline and either redoing it from the beginning or starting on my next timeline which I've been teasing here and there for a while now. Ultimately I decided to continue this since I'm finally past what I consider to be the most difficult part of the timeline and I owe you all a definitive ending to this story.

On the other hand the idea of redoing this timeline from the beginning is interesting. What would you change? Personally, I consider the first 30 chapters to be very strong, and I greatly enjoyed reading about the battles in the Morea, the daring blockade runs, and the sieges of Missilonghi. The abundance of larger than life characters really gave a lot of character to the story as well.

Wait who said anything about him saving the Union!

Whoa, whoa, whoa! Don't you be doing the son of my hero JQA dirty like that!

The chapter "The New Order" has both the most recent map of Greece and the most recent World Map.Is there a official map for this timeline?

Chapter 86: The New Order

Thanks!The chapter "The New Order" has both the most recent map of Greece and the most recent World Map.

Chapter 86: The New Order

So I got distracted and ended up forgetting to post the next chapter yesterday.  This time, though I will be posting it right after this!

This time, though I will be posting it right after this!

Aside from that, I thought about changing up some of the events elsewhere in the world so they were less similar to OTL. I also feel like my writing is better now than it was 6 years ago when I first started writing this timeline, so I'd mostly be adding more details and artistic flourishes to the text so its more engaging for you all.

I've considered changing the POD from the Battle of Dervenakia and Theodoros Kolokotronis' death to the Battle of Karpenisi and averting Markos Botsaris' death. While I originally felt like Koloktronis was a destabilizing influence in the OTL War of Independence, I realize that killing him off deprived me of a great character that could add some much needed tension and intrigue to early post war Greece. I've also thought about adding more detail to the War for Independence, featuring some episodes from other regions of the conflict like the Pelion Peninsula and some mountainous regions of Macedon which both held out against Ottoman invasions for several months and were only put down well after TTL's POD.Hearing this is slightly disheartening but unsurprising. I've been hit by month long writers block before, or life just getting too busy, and it takes a lot to go back to a project that has been on the back burner.

On the other hand the idea of redoing this timeline from the beginning is interesting. What would you change? Personally, I consider the first 30 chapters to be very strong, and I greatly enjoyed reading about the battles in the Morea, the daring blockade runs, and the sieges of Missilonghi. The abundance of larger than life characters really gave a lot of character to the story as well.

Aside from that, I thought about changing up some of the events elsewhere in the world so they were less similar to OTL. I also feel like my writing is better now than it was 6 years ago when I first started writing this timeline, so I'd mostly be adding more details and artistic flourishes to the text so its more engaging for you all.

Don't worry I have plans in store for him!Whoa, whoa, whoa! Don't you be doing the son of my hero JQA dirty like that!

Couldnt you just write some chapters to fill what you wanted to describe ?So I got distracted and ended up forgetting to post the next chapter yesterday.This time, though I will be posting it right after this!

I've considered changing the POD from the Battle of Dervenakia and Theodoros Kolokotronis' death to the Battle of Karpenisi and averting Markos Botsaris' death. While I originally felt like Koloktronis was a destabilizing influence in the OTL War of Independence, I realize that killing him off deprived me of a great character that could add some much needed tension and intrigue to early post war Greece. I've also thought about adding more detail to the War for Independence, featuring some episodes from other regions of the conflict like the Pelion Peninsula and some mountainous regions of Macedon which both held out against Ottoman invasions for several months and were only put down well after TTL's POD.

Aside from that, I thought about changing up some of the events elsewhere in the world so they were less similar to OTL. I also feel like my writing is better now than it was 6 years ago when I first started writing this timeline, so I'd mostly be adding more details and artistic flourishes to the text so its more engaging for you all.

Don't worry I have plans in store for him!

Chapter 99: Captains of Industry

Chapter 99: Captains of Industry

The Port of Laurium; Greece's burgeoning industrial center (circa 1870)

Aiding with the transition of the previous Kanaris Government with the new Kolokotronis Administration was the continuation of many policies and directives established during the previous administration. This would be seen most clearly in regards to foreign policy which maintained close relations with the United Kingdom, France and Russia. Religious and cultural policy would also see little changes under the Kolokotronis Regime, with a similar impetus dedicated to preserving ancient sites across the land and Hellenization of the various minorities in the Country. Finally, the Kolokotronis Government’s views on the prerogatives of the State differed little if at all between the two regimes, with both enjoying a strong working relationship with the King and both maintaining a healthy respect for the prerogatives of the Monarchy so long as the Monarchy continued to cooperate with and respect the Legislature. Yet, that is not to say that there were not differences between the two; there most certainly were. Kolokotronis’ stances on other issues such as the military and economy featured distinct differences that would become more apparent within a few months.

The Kanaris Governments had generally favored a hands off or laissez faire approach to the economy, only choosing to intervene directly to further develop Greece’s maritime infrastructure or in the event of emergencies that threatened the stability of the Greek State. The former was seen primarily through his development of numerous ports and maritime infrastructure across the country, culminating in the construction of the Corinth Canal in 1862. Meanwhile, the latter was seen through his implementation of the 1859 Land Reform Act, abolishing the dreaded Chiflik system in Thessaly and Epirus following the infamous Farmer’s March. Whilst this decision was certainly a step in the right direction there were still some problems that became evident, it was also heavy handed in some respects regarding larger landowners and overly inadequate in others.

Upon assuming Office in March of 1864, the Panos Kolokotronis Administration would improve upon the previous the 1859 Land Reform Act, by extending its effects to all of Greece. Due to certain technicalities and loopholes hidden within the text of the law, the protections afforded to small landholders were only guaranteed to farmers in Thessaly and Epirus, not all of Greece. On the surface this wasn’t a major concern in Athens as the Chiflik system was long dead in the Old Provinces[1]. However, digging deeper, one could find a fair degree of absentee landlordism across the country along with several cases of exploitation of gullible planters being swindled out of their properties at below market rates. This was amended under the amended Land Reform Act in 1865, as land holders in Greece were formally divided into two categories for administrative purposes; small landowners who owned 25 acres or less and large landowners who owned more than 25 acres with various protections afforded to each.[2]

To aid smaller planters, interest rates for government loans were set at a standard rate of 6% nationwide, whilst larger plantation owners were charged nearly double at an interest rate of 10%. The 1865 Land Reform Act would once more condemn the practice of slavery, serfdom, and indentured servitude as unjust, inhumane, and illegal in the lands of Greece. However, it would permit the establishment of contract laborers and tenant farmers so long as a third party (usually a government official or public notary) was present at the contract signing to ensure that the tenants were not taken advantage of by the prospective employer. Additionally, these same officials would be required to make random inspections of the property to ensure that the situation remained favorable to all parties. Finally, the provision preventing the selling of property was reduced from 5 years to 3 so long as neighboring small landowners were given an opportunity to purchase the property.

There was also a slight revision in this new Act which benefited larger landowners. Whereas before, absenteeism of eight months would be automatically punished with the forfeiture of the entire farmstead to the Government, now large landholders were now permitted to retain their properties provided they paid a small fine to the Hellenic Government, with the amount paid dependent upon the size of the plantation in question. However, should the landholder in question continue their absenteeism from the property, then an additional fine would be assessed for every month thereafter up to 12 months in total. At this time, the original penalty would be reimposed, and the property would be deemed vacant. Should the landholder wish to contest this decision, they would be required to make an appeal to a court of law, with the resulting ruling being made on a case-by-case basis.

Several Orchards near Agios Vasileios, Crete

Whilst land reform was certainly helpful to many Greek farmers, this wasn’t the only aspect of the Greek economy that the Kolokotronis Administration would touch upon as Greece’s heavier industries also received some much-needed attention and investment. Much of this renewed focus would go towards the Mines of Laurium which was quickly developing into Greece’s industrial epicenter. With its proven deposits of silver, lead, iron and zinc it had the potential to pull the Greek Economy into the Modern era and yet, since its reopening in 1839 its production had been rather disappointing.

Much of this can be blamed on the poor management of the Laurium Metallurgical Company whose primary focus up to this point had been the mining of silver and lead owing to their higher value. Yet, even with 25 years of continuous operations at Laurium, the Company had only succeeded in producing a meager 12 imperial tons of silver and a little over 8,000 tons of lead in 1861, with lower totals reported in every year before and since.[3] Moreover, the continued neglect of Laurium’s iron and zinc deposits was also baffling for the Hellenic Government who sought to exploit the site’s resources to the fullest. It would soon become clear what was happening at Laurium, as discrepancies with its recorded production and actual production.

Unbeknownst to the Hellenic Government, either through a lack of oversight or ignorance, the Laurium Metallurgical Company – a joint French-Hellenic Mining syndicate, had been making up the shortfalls in its silver production through the selling of ancient lead and silver tailings found at the site, known as ekvolades in Greece. As this product was not mined from the earth, but rather picked off the ground it wasn’t subject to mining regulations regarding the taxing of the company’s findings. No one knows when exactly this practice began at the site, but upon the discovery of this practice in early 1865, the Kolokotronis Government would swiftly move to strip the Laurium Metallurgy Company of their permits, inciting a long and arduous legal battle and diplomatic confrontation with France who came to the defense of the Company.

Tensions nearly boiled over as the Kolokotronis Government threatened to nationalize the Company and all their assets without compensation. In response, the French Ambassador Arthur de Gobineau promised to call upon the French Mediterranean Squadron and blockade Piraeus, Laurium and other ports in Attica if such an act were carried out. This state of affairs would continue off and on for months, until finally a breakthrough emerged when the Hellenic Government offered to buy back the mining rights at Laurium, to which the Company agreed. Meanwhile, to sooth relations with France, the Greek Government would agree to a new trade deal selling excess ore to Paris in exchange for various French made commodities like munitions and machinery. Finally, new regulations would be put in place taxing the sale of ancient tailings in Greece, closing this loophole once and for all.[4]

Under the management of a new company, the appropriately named Hellenic Minerals and Metals Extraction Syndicate (later renamed to the much simpler Hellenic Minerals), the miners of Laurium would finally begin extracting zinc and iron ore from the site. Thus, over the ensuing months, half a dozen new mines would open across the southern tip of Attica in pursuit of these precious metals. One last development at Laurium would be carried out in early 1869, when the Kolokotronis Government issued a permit for the construction of a new blast furnace smelting facility at Laurium to test the viability of the Bessemer Process. Although it wouldn’t be complete until the end of the start of the 1870’s, it would eventually confirm that the Bessemer Process was within the means of the Greek State, albeit on a moderate scale.

A map depicting various mines in the Laurium region of Attica (circa 1900)

There were also several other mining developments elsewhere in Greece during this time as a primitive new iron ore mining facility would be opened at Larymna in early 1868, bolstering Greece’s meager iron ore production. A new marble mining facility would be opened on the north slope of Mount Pantelicus to help supply Pentelic marble for the refurbishment of Athens’ ancient structures in preparation for the 1866 Olympic Games. Finally, several companies in the Peloponnese were given permission to explore for additional coal deposits in the hills surrounding the city of Megalopolis.

Whilst these were all certainly important economic developments for Greece; commerce and trade remained Greece’s the lifeblood of the Greek Economy and Panos’ largest contribution to this sector of the Hellenic Economy would be through his expansion of Greece’s landward infrastructure. Beginning in the Autumn of 1864, the Kolokotronis Administration would authorize the construction of over 200 miles of new paved roads in Crete and the Peloponnese, a new bridge spanning the Euripus Strait, a bridge over the Arachthos River near Arta, a dozen new lighthouses such as those at Santorini and Rhodes, and new aqueducts for Athens, Patras and Heraklion among several other less noteworthy projects. Similarly, Athens’ sewer system was renovated and expanded for the first time in centuries as the city was rapidly approaching 100,000 inhabitants and was suffering from increasing issues with health and cleanliness. However, the cornerstone of Panos’ economic investment programs would be his infamous Hellenic Rail Act of 1865 which approved contracts and government funding for a dozen new railways across the Country.

The Lighthouse of Akrotini - located on the isle of Santorini (constructed circa 1869).

At the start of his term in 1864, Greece’s railroad network stood at less than 90 miles or roughly 145 kilometers divided between five active railroads and a smattering of other projects that were in varying stages of development.[5] By the end of Panos Kolokotronis’ Premiership this number would more than triple with the completion of 9 new railroads and two more finishing soon after. Most of these new railways were smaller lines that connected various ports to other population centers further in land such as the Chalcis-Dirfys line that was completed in 1867, the Missolonghi-Agrinio Line opened in 1870, or the Diakopto-Kalavryta line which began operating in 1873. Yet, there was one that was much more ambitious and perhaps more strategically important than any of these minor railways. This was a single rail line running from Athens to Larissa, tying the richer and more developed South of Greece with the more rural and less integrated North of Greece.

At nearly 400km (~250 miles); the Athens-Larissa Railway would be the longest line yet in Greece. Traversing through several mountainous passes and crossing multiple rivers, it was a colossal undertaking for any country at the time, let alone little Greece. Complicating planning even further were later additions for two auxiliary lines that connected the Aegean entrepot of Demetrias, and the Western Thessalian population centers of Trikala, Karditsa, and Kalambaka to this main line adding another 150 kms (93 miles) to the project. Despite the immense challenges involved, several competitors would emerge for the contract to build and manage the new railway. Eventually a contract would be reached leading numerous surveyors to chart a safe course from the Capital city of Athens to Larissa. By the beginning of Spring 1865, a general route had been established, prompting the government to dispatch a company of engineers and laborers to begin clearing the path. As this was taking place, orders for nearly 550 kilometers of rail were placed with various distributors across the country. However, several issues would soon emerge for the project.

First and foremost, producing this much rail would take time, a lot of time as Greece’s rail production industry was practically non-existent in 1865. Part of this was due to the relative inexpensiveness of sea travel in Greece which disincentivized railroad construction and by effect, rail production over the past few decades. Given their infrequent construction, railroads were viewed as a rather niche venture by most metal smiths in the country and were only produced on a case-by-case basis in the past and usually for marked up rates. As there wasn’t exactly a strong or profitable market for making this much rail in Greece, only a handful of smithies scattered across Greece even had the experience or know-how to construct railway tracks, let alone the tools or techniques.

Perhaps more important to the issue of limited rail production was the relatively small iron working industry in Greece which only totaled about 200,000 tons per annum. This sum was in turn divided between the production of tools, ships, and ornaments or was refined further into steel.[6] Some of this ore was even exported abroad given Greece’s limited manufacturing and refinery capabilities. The opening of iron mines at Laurium and Larymna in 1865 and 1868 respectively, would help alleviate this issue boosting Greek iron production to nearly 400,000 tons by the end of the century, but it would take time before they were producing any meaningful supplies of iron ore.

There was also another problem, as those smithy companies that did possess the means to refine the ore had their own differing standards for rail quality and rail fastening systems. Often times, the type of iron used in rails often differed between smithy and furnaces, with some making cast iron rails, whilst others created wrought iron. Generally, most lines were comprised entirely of one or the other, but in the odd case of the Laurium-Athens railroad it used both given its (at the time) rather extensive length. Naturally, this resulted in segments made of cast iron eventually cracking under continued usage, culminating in the costly derailment of a freight train in September 1861 and the death of its four operators. Other common issues were the wide variety of fastener systems which ranged from stakes or spikes of varying quality, shapes and sizes which either provided too little flexibility to the rails causing them to break under pressure, or too much flexibility, causing them to gradually shift their course and completely breaking free of their fasteners in some instances.

One last issue was the differing gauges of the various tracks in Greece. Some railroads, particularly those in the Peloponnese used Meter Gauge - tracks that were spaced one meter apart. Meter Gauge was particularly popular with the French at the time and had proven quite receptive in parts of the Morea, specifically those regions where French business interests were largely focused. In contrast other railways, primarily those in Attica had generally used what is now known as Narrow Gauge with most being around 600mm. As the new line was supposed to tie into the Athens-Piraeus line, many supported making it Narrow Gauge as well. However, some championed the use of 1435 mm, or what is now referred to as Standard Gauge. Standard Gauge had become increasingly popular amongst the British, who cited its greater efficiency compared to narrower gauge railways which couldn’t carry heavier freight and broader gauge railways which had trouble in rugged terrain.

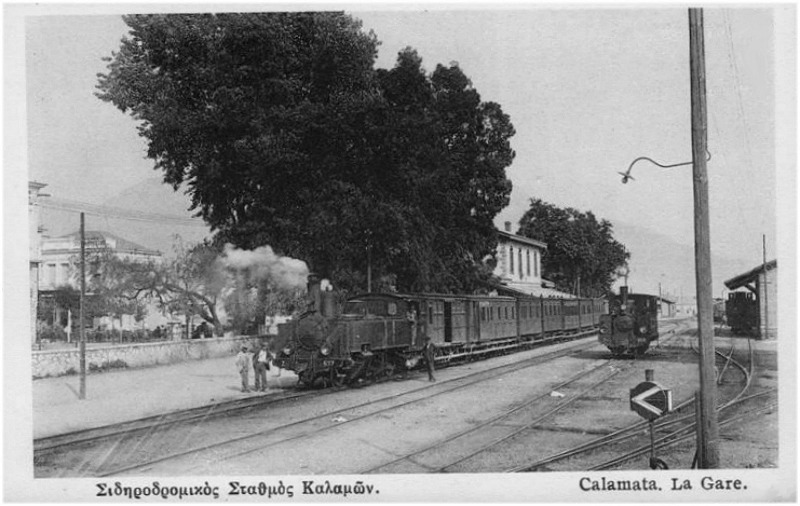

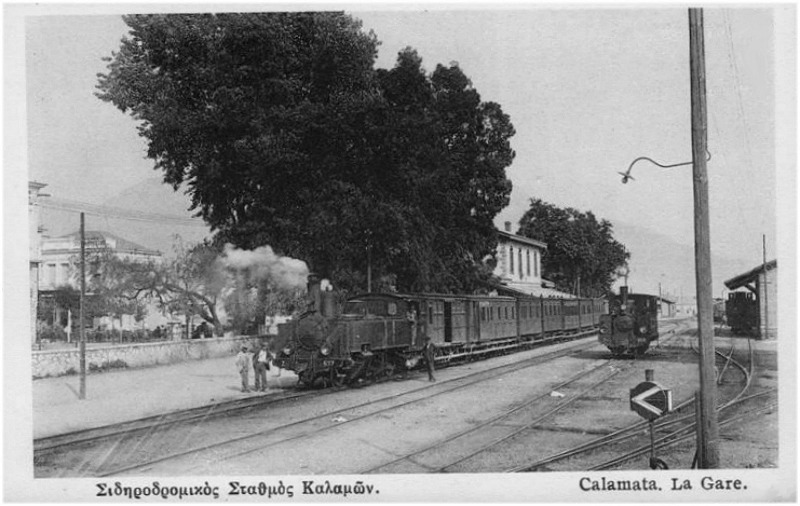

A Train in Kalamata using Meter Gauge

To resolve these many issues and provide a continuing regulatory body to oversee all future infrastructure projects; the Hellenic Government would split the Departments of Infrastructure and Development from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and establish a new Agency; the Ministry of Infrastructure, Transportation, and Economic Development, or simply the Ministry of Infrastructure for short. It’s first Minister would be the talented Representative from Messinia Alexandros Koumoundouros who had spent time as both the Deputy Minister of Finance for Economic Development and the Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs for Infrastructure before being elevated to a full Minister in his own right in late 1865. Koumoundouros’ Ministry would be charged with standardizing rail production and construction across the country in accordance with the norms of the times throughout Europe; that being wrought iron rails with timber sleepers and tie plate fasteners. They would sit upon a bedding of rock and gravel ballast, providing a porous, yet relatively even surface for the ties to sit within securely. Finally, the gauge of the rails would be set at the Stephenson Gauge of 1435 millimeters (Standard Gauge).

The latter decision proved quite divisive as many Representatives from the Peloponnese and Attica opposed the shift to British Standard Gauge as it would force preexisting Railroads to change their gauges in accordance with this new standard. However, as the United Kingdom was the chief supplier of rail cars for the Hellenic Kingdom - almost all of which were now being produced with Standard Gauge wheelsets - this argument carried less weight than it might have otherwise. It also cannot be denied that Panos Kolokotronis likely forced this decision given he had been one of the original proponents of 1435mm gauge only months prior. As such, all new lines would be constructed in Standard Gauge. Yet, in the spirit of compromise it was decided that preexisting lines utilizing Meter or Narrow Gauges would be allowed to continue operating whilst being gradually replaced with Standard Gauge lines.

With the necessary prep work complete by the end of 1865, construction was officially set to begin the following year in early 1866. The first leg of the line would see the mainland port of Chalcis connected to Athens by the end of 1866. However, despite this early success, wrought iron supply shortages hampered construction efforts considerably. More than that, the project was incredibly expensive, with the estimated total of the 1865 Hellenic Rail Act (all 900kms of it) costing around 80 million Drachma (~3.5 million Pounds Sterling), or roughly 1.5 times the annual revenue stream of the entire Hellenic Government in 1865, prompting the acceptance of a number of loans to help finance the project in a timely manner. This combined with the collapse of the bridge over the Sperchios River following a particularly wet Winter in 1869 effectively halted construction just shy of the city of Lamia as more funds needed to be appropriated to fund a new bridge. Thus, by the start of the One Year War in 1871, only half of the main railway was complete; still an impressive feat for Greece, but nevertheless, disappointing after the considerable resources invested in the project.

Whilst there were certainly economic benefits to these endeavors, the real boon of this project would be the strategic ramifications it would bring to Greece as troops and supplies could be more easily shifted from the South to the North in the event of War with the Turks. And War with the Turks was the true goal of Panos Kolokotronis. Although he had come to terms with the fact that Greece needed cordial relations with its Northern neighbor, he himself despised the Ottoman Empire for having murdered his father and despoiling his homeland. Thus, the remainder of his life would be dedicated to the complete destruction of the Turk. However, Panos Kolokotronis was no longer a young man who was easily blinded by rage. He knew full well that Greece stood little chance against the Ottoman Empire as it was now and to that end he made preparations to bring about its destruction.

Next Time: The Balkan League

[1] Old Provinces is a reference to the territories of Pre-1855 Greece which include the Peloponnese, Attica-Boeotia, Aetolia-Acarnania, Phthiotis-Phocis, Crete, the Cyclades, and Chios-Samos.

[2] 15-20 acres is generally defined as the minimum required for self-sustenance, whilst 25 acres provides these farmers with some margin for crops failing and something they can sell and make a minor profit from. Obviously, this is not a perfect system, but it is a step in the right direction.

[3] According to the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica, Greece in 1905 produced roughly 165,000 tons of dressed lead with about 14,000 tons being silver pig lead. This in turn produced about 1600 to 1900 grams of silver ore per ton, which range anywhere from 807881 ounces to 931233 ounces of silver, or 22 to 26 tons of silver ore. For simplicity, I averaged the two together for 24 tons of silver and then halved this number to account for the lacking technological innovations in the intervening 40 years and for story reasonings listed above. If the mines hadn’t been operational for nearly 25 years by now ITTL, then I’d consider making it even lower but I feel as if 12 tons is good enough.

[4] A reference to the OTL Lavrion issue. For those unfamiliar, the Laurium Mines were opened in the 1860s in OTL and were operated by a French-Italian company named Roux - Serpieri - Fressynet CIE. The Company would utilize a loophole in Greek Tax law by selling the Evkolades – tailings from the ancient mining activity, which were unfortunately overlooked in the original contract negotiations.

[5] These railroads are, in no particular order: Athens-Piraeus, Laurium-Athens, Kalamata-Messini, Pyrgos-Katakolo, and Lamia-Stilis.

[6] Greek iron ore production in 1905 was listed at around 460,000 tons according to the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica. Given technological differences between the early 1900’s and 1860’s, I’ve adjusted this downward somewhat.

The Port of Laurium; Greece's burgeoning industrial center (circa 1870)

Aiding with the transition of the previous Kanaris Government with the new Kolokotronis Administration was the continuation of many policies and directives established during the previous administration. This would be seen most clearly in regards to foreign policy which maintained close relations with the United Kingdom, France and Russia. Religious and cultural policy would also see little changes under the Kolokotronis Regime, with a similar impetus dedicated to preserving ancient sites across the land and Hellenization of the various minorities in the Country. Finally, the Kolokotronis Government’s views on the prerogatives of the State differed little if at all between the two regimes, with both enjoying a strong working relationship with the King and both maintaining a healthy respect for the prerogatives of the Monarchy so long as the Monarchy continued to cooperate with and respect the Legislature. Yet, that is not to say that there were not differences between the two; there most certainly were. Kolokotronis’ stances on other issues such as the military and economy featured distinct differences that would become more apparent within a few months.

The Kanaris Governments had generally favored a hands off or laissez faire approach to the economy, only choosing to intervene directly to further develop Greece’s maritime infrastructure or in the event of emergencies that threatened the stability of the Greek State. The former was seen primarily through his development of numerous ports and maritime infrastructure across the country, culminating in the construction of the Corinth Canal in 1862. Meanwhile, the latter was seen through his implementation of the 1859 Land Reform Act, abolishing the dreaded Chiflik system in Thessaly and Epirus following the infamous Farmer’s March. Whilst this decision was certainly a step in the right direction there were still some problems that became evident, it was also heavy handed in some respects regarding larger landowners and overly inadequate in others.

Upon assuming Office in March of 1864, the Panos Kolokotronis Administration would improve upon the previous the 1859 Land Reform Act, by extending its effects to all of Greece. Due to certain technicalities and loopholes hidden within the text of the law, the protections afforded to small landholders were only guaranteed to farmers in Thessaly and Epirus, not all of Greece. On the surface this wasn’t a major concern in Athens as the Chiflik system was long dead in the Old Provinces[1]. However, digging deeper, one could find a fair degree of absentee landlordism across the country along with several cases of exploitation of gullible planters being swindled out of their properties at below market rates. This was amended under the amended Land Reform Act in 1865, as land holders in Greece were formally divided into two categories for administrative purposes; small landowners who owned 25 acres or less and large landowners who owned more than 25 acres with various protections afforded to each.[2]

To aid smaller planters, interest rates for government loans were set at a standard rate of 6% nationwide, whilst larger plantation owners were charged nearly double at an interest rate of 10%. The 1865 Land Reform Act would once more condemn the practice of slavery, serfdom, and indentured servitude as unjust, inhumane, and illegal in the lands of Greece. However, it would permit the establishment of contract laborers and tenant farmers so long as a third party (usually a government official or public notary) was present at the contract signing to ensure that the tenants were not taken advantage of by the prospective employer. Additionally, these same officials would be required to make random inspections of the property to ensure that the situation remained favorable to all parties. Finally, the provision preventing the selling of property was reduced from 5 years to 3 so long as neighboring small landowners were given an opportunity to purchase the property.

There was also a slight revision in this new Act which benefited larger landowners. Whereas before, absenteeism of eight months would be automatically punished with the forfeiture of the entire farmstead to the Government, now large landholders were now permitted to retain their properties provided they paid a small fine to the Hellenic Government, with the amount paid dependent upon the size of the plantation in question. However, should the landholder in question continue their absenteeism from the property, then an additional fine would be assessed for every month thereafter up to 12 months in total. At this time, the original penalty would be reimposed, and the property would be deemed vacant. Should the landholder wish to contest this decision, they would be required to make an appeal to a court of law, with the resulting ruling being made on a case-by-case basis.

Several Orchards near Agios Vasileios, Crete

Whilst land reform was certainly helpful to many Greek farmers, this wasn’t the only aspect of the Greek economy that the Kolokotronis Administration would touch upon as Greece’s heavier industries also received some much-needed attention and investment. Much of this renewed focus would go towards the Mines of Laurium which was quickly developing into Greece’s industrial epicenter. With its proven deposits of silver, lead, iron and zinc it had the potential to pull the Greek Economy into the Modern era and yet, since its reopening in 1839 its production had been rather disappointing.

Much of this can be blamed on the poor management of the Laurium Metallurgical Company whose primary focus up to this point had been the mining of silver and lead owing to their higher value. Yet, even with 25 years of continuous operations at Laurium, the Company had only succeeded in producing a meager 12 imperial tons of silver and a little over 8,000 tons of lead in 1861, with lower totals reported in every year before and since.[3] Moreover, the continued neglect of Laurium’s iron and zinc deposits was also baffling for the Hellenic Government who sought to exploit the site’s resources to the fullest. It would soon become clear what was happening at Laurium, as discrepancies with its recorded production and actual production.

Unbeknownst to the Hellenic Government, either through a lack of oversight or ignorance, the Laurium Metallurgical Company – a joint French-Hellenic Mining syndicate, had been making up the shortfalls in its silver production through the selling of ancient lead and silver tailings found at the site, known as ekvolades in Greece. As this product was not mined from the earth, but rather picked off the ground it wasn’t subject to mining regulations regarding the taxing of the company’s findings. No one knows when exactly this practice began at the site, but upon the discovery of this practice in early 1865, the Kolokotronis Government would swiftly move to strip the Laurium Metallurgy Company of their permits, inciting a long and arduous legal battle and diplomatic confrontation with France who came to the defense of the Company.

Tensions nearly boiled over as the Kolokotronis Government threatened to nationalize the Company and all their assets without compensation. In response, the French Ambassador Arthur de Gobineau promised to call upon the French Mediterranean Squadron and blockade Piraeus, Laurium and other ports in Attica if such an act were carried out. This state of affairs would continue off and on for months, until finally a breakthrough emerged when the Hellenic Government offered to buy back the mining rights at Laurium, to which the Company agreed. Meanwhile, to sooth relations with France, the Greek Government would agree to a new trade deal selling excess ore to Paris in exchange for various French made commodities like munitions and machinery. Finally, new regulations would be put in place taxing the sale of ancient tailings in Greece, closing this loophole once and for all.[4]

Under the management of a new company, the appropriately named Hellenic Minerals and Metals Extraction Syndicate (later renamed to the much simpler Hellenic Minerals), the miners of Laurium would finally begin extracting zinc and iron ore from the site. Thus, over the ensuing months, half a dozen new mines would open across the southern tip of Attica in pursuit of these precious metals. One last development at Laurium would be carried out in early 1869, when the Kolokotronis Government issued a permit for the construction of a new blast furnace smelting facility at Laurium to test the viability of the Bessemer Process. Although it wouldn’t be complete until the end of the start of the 1870’s, it would eventually confirm that the Bessemer Process was within the means of the Greek State, albeit on a moderate scale.

A map depicting various mines in the Laurium region of Attica (circa 1900)

There were also several other mining developments elsewhere in Greece during this time as a primitive new iron ore mining facility would be opened at Larymna in early 1868, bolstering Greece’s meager iron ore production. A new marble mining facility would be opened on the north slope of Mount Pantelicus to help supply Pentelic marble for the refurbishment of Athens’ ancient structures in preparation for the 1866 Olympic Games. Finally, several companies in the Peloponnese were given permission to explore for additional coal deposits in the hills surrounding the city of Megalopolis.

Whilst these were all certainly important economic developments for Greece; commerce and trade remained Greece’s the lifeblood of the Greek Economy and Panos’ largest contribution to this sector of the Hellenic Economy would be through his expansion of Greece’s landward infrastructure. Beginning in the Autumn of 1864, the Kolokotronis Administration would authorize the construction of over 200 miles of new paved roads in Crete and the Peloponnese, a new bridge spanning the Euripus Strait, a bridge over the Arachthos River near Arta, a dozen new lighthouses such as those at Santorini and Rhodes, and new aqueducts for Athens, Patras and Heraklion among several other less noteworthy projects. Similarly, Athens’ sewer system was renovated and expanded for the first time in centuries as the city was rapidly approaching 100,000 inhabitants and was suffering from increasing issues with health and cleanliness. However, the cornerstone of Panos’ economic investment programs would be his infamous Hellenic Rail Act of 1865 which approved contracts and government funding for a dozen new railways across the Country.

The Lighthouse of Akrotini - located on the isle of Santorini (constructed circa 1869).

At the start of his term in 1864, Greece’s railroad network stood at less than 90 miles or roughly 145 kilometers divided between five active railroads and a smattering of other projects that were in varying stages of development.[5] By the end of Panos Kolokotronis’ Premiership this number would more than triple with the completion of 9 new railroads and two more finishing soon after. Most of these new railways were smaller lines that connected various ports to other population centers further in land such as the Chalcis-Dirfys line that was completed in 1867, the Missolonghi-Agrinio Line opened in 1870, or the Diakopto-Kalavryta line which began operating in 1873. Yet, there was one that was much more ambitious and perhaps more strategically important than any of these minor railways. This was a single rail line running from Athens to Larissa, tying the richer and more developed South of Greece with the more rural and less integrated North of Greece.

At nearly 400km (~250 miles); the Athens-Larissa Railway would be the longest line yet in Greece. Traversing through several mountainous passes and crossing multiple rivers, it was a colossal undertaking for any country at the time, let alone little Greece. Complicating planning even further were later additions for two auxiliary lines that connected the Aegean entrepot of Demetrias, and the Western Thessalian population centers of Trikala, Karditsa, and Kalambaka to this main line adding another 150 kms (93 miles) to the project. Despite the immense challenges involved, several competitors would emerge for the contract to build and manage the new railway. Eventually a contract would be reached leading numerous surveyors to chart a safe course from the Capital city of Athens to Larissa. By the beginning of Spring 1865, a general route had been established, prompting the government to dispatch a company of engineers and laborers to begin clearing the path. As this was taking place, orders for nearly 550 kilometers of rail were placed with various distributors across the country. However, several issues would soon emerge for the project.

First and foremost, producing this much rail would take time, a lot of time as Greece’s rail production industry was practically non-existent in 1865. Part of this was due to the relative inexpensiveness of sea travel in Greece which disincentivized railroad construction and by effect, rail production over the past few decades. Given their infrequent construction, railroads were viewed as a rather niche venture by most metal smiths in the country and were only produced on a case-by-case basis in the past and usually for marked up rates. As there wasn’t exactly a strong or profitable market for making this much rail in Greece, only a handful of smithies scattered across Greece even had the experience or know-how to construct railway tracks, let alone the tools or techniques.

Perhaps more important to the issue of limited rail production was the relatively small iron working industry in Greece which only totaled about 200,000 tons per annum. This sum was in turn divided between the production of tools, ships, and ornaments or was refined further into steel.[6] Some of this ore was even exported abroad given Greece’s limited manufacturing and refinery capabilities. The opening of iron mines at Laurium and Larymna in 1865 and 1868 respectively, would help alleviate this issue boosting Greek iron production to nearly 400,000 tons by the end of the century, but it would take time before they were producing any meaningful supplies of iron ore.

There was also another problem, as those smithy companies that did possess the means to refine the ore had their own differing standards for rail quality and rail fastening systems. Often times, the type of iron used in rails often differed between smithy and furnaces, with some making cast iron rails, whilst others created wrought iron. Generally, most lines were comprised entirely of one or the other, but in the odd case of the Laurium-Athens railroad it used both given its (at the time) rather extensive length. Naturally, this resulted in segments made of cast iron eventually cracking under continued usage, culminating in the costly derailment of a freight train in September 1861 and the death of its four operators. Other common issues were the wide variety of fastener systems which ranged from stakes or spikes of varying quality, shapes and sizes which either provided too little flexibility to the rails causing them to break under pressure, or too much flexibility, causing them to gradually shift their course and completely breaking free of their fasteners in some instances.

One last issue was the differing gauges of the various tracks in Greece. Some railroads, particularly those in the Peloponnese used Meter Gauge - tracks that were spaced one meter apart. Meter Gauge was particularly popular with the French at the time and had proven quite receptive in parts of the Morea, specifically those regions where French business interests were largely focused. In contrast other railways, primarily those in Attica had generally used what is now known as Narrow Gauge with most being around 600mm. As the new line was supposed to tie into the Athens-Piraeus line, many supported making it Narrow Gauge as well. However, some championed the use of 1435 mm, or what is now referred to as Standard Gauge. Standard Gauge had become increasingly popular amongst the British, who cited its greater efficiency compared to narrower gauge railways which couldn’t carry heavier freight and broader gauge railways which had trouble in rugged terrain.

A Train in Kalamata using Meter Gauge

To resolve these many issues and provide a continuing regulatory body to oversee all future infrastructure projects; the Hellenic Government would split the Departments of Infrastructure and Development from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and establish a new Agency; the Ministry of Infrastructure, Transportation, and Economic Development, or simply the Ministry of Infrastructure for short. It’s first Minister would be the talented Representative from Messinia Alexandros Koumoundouros who had spent time as both the Deputy Minister of Finance for Economic Development and the Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs for Infrastructure before being elevated to a full Minister in his own right in late 1865. Koumoundouros’ Ministry would be charged with standardizing rail production and construction across the country in accordance with the norms of the times throughout Europe; that being wrought iron rails with timber sleepers and tie plate fasteners. They would sit upon a bedding of rock and gravel ballast, providing a porous, yet relatively even surface for the ties to sit within securely. Finally, the gauge of the rails would be set at the Stephenson Gauge of 1435 millimeters (Standard Gauge).

The latter decision proved quite divisive as many Representatives from the Peloponnese and Attica opposed the shift to British Standard Gauge as it would force preexisting Railroads to change their gauges in accordance with this new standard. However, as the United Kingdom was the chief supplier of rail cars for the Hellenic Kingdom - almost all of which were now being produced with Standard Gauge wheelsets - this argument carried less weight than it might have otherwise. It also cannot be denied that Panos Kolokotronis likely forced this decision given he had been one of the original proponents of 1435mm gauge only months prior. As such, all new lines would be constructed in Standard Gauge. Yet, in the spirit of compromise it was decided that preexisting lines utilizing Meter or Narrow Gauges would be allowed to continue operating whilst being gradually replaced with Standard Gauge lines.

With the necessary prep work complete by the end of 1865, construction was officially set to begin the following year in early 1866. The first leg of the line would see the mainland port of Chalcis connected to Athens by the end of 1866. However, despite this early success, wrought iron supply shortages hampered construction efforts considerably. More than that, the project was incredibly expensive, with the estimated total of the 1865 Hellenic Rail Act (all 900kms of it) costing around 80 million Drachma (~3.5 million Pounds Sterling), or roughly 1.5 times the annual revenue stream of the entire Hellenic Government in 1865, prompting the acceptance of a number of loans to help finance the project in a timely manner. This combined with the collapse of the bridge over the Sperchios River following a particularly wet Winter in 1869 effectively halted construction just shy of the city of Lamia as more funds needed to be appropriated to fund a new bridge. Thus, by the start of the One Year War in 1871, only half of the main railway was complete; still an impressive feat for Greece, but nevertheless, disappointing after the considerable resources invested in the project.

Whilst there were certainly economic benefits to these endeavors, the real boon of this project would be the strategic ramifications it would bring to Greece as troops and supplies could be more easily shifted from the South to the North in the event of War with the Turks. And War with the Turks was the true goal of Panos Kolokotronis. Although he had come to terms with the fact that Greece needed cordial relations with its Northern neighbor, he himself despised the Ottoman Empire for having murdered his father and despoiling his homeland. Thus, the remainder of his life would be dedicated to the complete destruction of the Turk. However, Panos Kolokotronis was no longer a young man who was easily blinded by rage. He knew full well that Greece stood little chance against the Ottoman Empire as it was now and to that end he made preparations to bring about its destruction.

Next Time: The Balkan League

[1] Old Provinces is a reference to the territories of Pre-1855 Greece which include the Peloponnese, Attica-Boeotia, Aetolia-Acarnania, Phthiotis-Phocis, Crete, the Cyclades, and Chios-Samos.

[2] 15-20 acres is generally defined as the minimum required for self-sustenance, whilst 25 acres provides these farmers with some margin for crops failing and something they can sell and make a minor profit from. Obviously, this is not a perfect system, but it is a step in the right direction.

[3] According to the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica, Greece in 1905 produced roughly 165,000 tons of dressed lead with about 14,000 tons being silver pig lead. This in turn produced about 1600 to 1900 grams of silver ore per ton, which range anywhere from 807881 ounces to 931233 ounces of silver, or 22 to 26 tons of silver ore. For simplicity, I averaged the two together for 24 tons of silver and then halved this number to account for the lacking technological innovations in the intervening 40 years and for story reasonings listed above. If the mines hadn’t been operational for nearly 25 years by now ITTL, then I’d consider making it even lower but I feel as if 12 tons is good enough.

[4] A reference to the OTL Lavrion issue. For those unfamiliar, the Laurium Mines were opened in the 1860s in OTL and were operated by a French-Italian company named Roux - Serpieri - Fressynet CIE. The Company would utilize a loophole in Greek Tax law by selling the Evkolades – tailings from the ancient mining activity, which were unfortunately overlooked in the original contract negotiations.

[5] These railroads are, in no particular order: Athens-Piraeus, Laurium-Athens, Kalamata-Messini, Pyrgos-Katakolo, and Lamia-Stilis.

[6] Greek iron ore production in 1905 was listed at around 460,000 tons according to the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica. Given technological differences between the early 1900’s and 1860’s, I’ve adjusted this downward somewhat.

Now this sounds ominous... who would be the potential members of a league against the Ottomans? Because I very much doubt Panos Kolokotronis of all people, can't count the balance of power or would ignore it. Serbia obviously, Montenegro but just an alliance of Greece, Serbia and Montenegro against even an Ottoman empire that is probably way more weaken than OTL at that time? As long as the Greek navy can control the Aegean the numbers may work, just like 1912 it makes moving troops from Asia to Europe very problematic while tying troops to protect the straits area. And to make things worse for the Ottomans they almost have no railroads in 1871.Thus, by the start of the One Year War in 1871, only half of the main railway was complete; still an impressive feat for Greece, but nevertheless, disappointing after the considerable resources invested in the project.

Whilst there were certainly economic benefits to these endeavors, the real boon of this project would be the strategic ramifications it would bring to Greece as troops and supplies could be more easily shifted from the South to the North in the event of War with the Turks. And War with the Turks was the true goal of Panos Kolokotronis. Although he had come to terms with the fact that Greece needed cordial relations with its Northern neighbor, he himself despised the Ottoman Empire for having murdered his father and despoiling his homeland. Thus, the remainder of his life would be dedicated to the complete destruction of the Turk. However, Panos Kolokotronis was no longer a young man who was easily blinded by rage. He knew full well that Greece stood little chance against the Ottoman Empire as it was now and to that end he made preparations to bring about its destruction.

But it still looks to me like a rather more hairy affair than OTL so where else would Kolokotronis be looking for allies and he most assuredly looking for more? Revolts in Bulgaria, Macedonia, Bosnia and possibly even Albania? This looks an obvious one, not just to tie down Ottoman troops but also as an excuse for war and to generate political support. Wallachia and Moldavia are likely out of the question, for the league to work it needs to be western leaning not look like Russian puppets. Which leaves as the other obvious member for Athens to seek as an ally... Egypt. If Egyptian armies are marching into Syria tying down the Anatolian ordus.

Will have to see who is actually in the war and how it goes on land... but no matter what happens in Macedonia, there are two obvious places for the Greeks to make permanent gains even if they lose the general war. The remaining North Aegean islands and Cyprus. And yes I'm making the assumption Kolokotronis has not gotten a case of the stupids to go to war without the Greek navy being superior. Which means in 1871 ironclads from British yards and we have not heard anything about it yet. In OTL the Ottomans in 1871 had 13 ironclads or various sizes 9 of them completed in 1870. But of these 4 were Egyptian ships denied to the Egyptians and delivered instead to the Ottomans. So you are down to 9, TTL Egypt will be getting their ships. The rest are something of a mixed bag, the 4 Osmaniye's are broadside ironclads already getting obsolescent (their artillery at least) despite being only 5 years old, Asar-I-Tevfik is likely the best one, the last 4 smallish casemate ironclads. And TTL the Ottomans have rather more severe economic issues to go into a shopping spree while also needing to rebuild their army from scratch...

The One Year War? Is that the equivalent of the OTL Balkan Wars of 1912-13?Thus, by the start of the One Year War in 1871, only half of the main railway was complete;

Suffice to say, the next chapter will detail the states and non state actors involved in this Balkan League. I'll also make sure to cover the state of the Ottoman Empire and what events serve as the casus belli for this conflict. Finally, I'll do a chapter on the Hellenic Army and Navy prior to the war as well so we can see how strong they are at the start of the conflict.Now this sounds ominous... who would be the potential members of a league against the Ottomans? Because I very much doubt Panos Kolokotronis of all people, can't count the balance of power or would ignore it. Serbia obviously, Montenegro but just an alliance of Greece, Serbia and Montenegro against even an Ottoman empire that is probably way more weaken than OTL at that time? As long as the Greek navy can control the Aegean the numbers may work, just like 1912 it makes moving troops from Asia to Europe very problematic while tying troops to protect the straits area. And to make things worse for the Ottomans they almost have no railroads in 1871.

But it still looks to me like a rather more hairy affair than OTL so where else would Kolokotronis be looking for allies and he most assuredly looking for more? Revolts in Bulgaria, Macedonia, Bosnia and possibly even Albania? This looks an obvious one, not just to tie down Ottoman troops but also as an excuse for war and to generate political support. Wallachia and Moldavia are likely out of the question, for the league to work it needs to be western leaning not look like Russian puppets. Which leaves as the other obvious member for Athens to seek as an ally... Egypt. If Egyptian armies are marching into Syria tying down the Anatolian ordus.

Will have to see who is actually in the war and how it goes on land... but no matter what happens in Macedonia, there are two obvious places for the Greeks to make permanent gains even if they lose the general war. The remaining North Aegean islands and Cyprus. And yes I'm making the assumption Kolokotronis has not gotten a case of the stupids to go to war without the Greek navy being superior. Which means in 1871 ironclads from British yards and we have not heard anything about it yet. In OTL the Ottomans in 1871 had 13 ironclads or various sizes 9 of them completed in 1870. But of these 4 were Egyptian ships denied to the Egyptians and delivered instead to the Ottomans. So you are down to 9, TTL Egypt will be getting their ships. The rest are something of a mixed bag, the 4 Osmaniye's are broadside ironclads already getting obsolescent (their artillery at least) despite being only 5 years old, Asar-I-Tevfik is likely the best one, the last 4 smallish casemate ironclads. And TTL the Ottomans have rather more severe economic issues to go into a shopping spree while also needing to rebuild their army from scratch...

Maybe, maybe not, but its definitely modeled after one of the Wars between the Ottomans and the Greeks.The One Year War? Is that the equivalent of the OTL Balkan Wars of 1912-13?

I short of have my opinions on what a 1871 Greek army and navy would look like... which for now will keep to myself.Suffice to say, the next chapter will detail the states and non state actors involved in this Balkan League. I'll also make sure to cover the state of the Ottoman Empire and what events serve as the casus belli for this conflict. Finally, I'll do a chapter on the Hellenic Army and Navy prior to the war as well so we can see how strong they are at the start of the conflict.

1897 is out because the Greek army is not an untrained mess as it was in OTL. Just sayingMaybe, maybe not, but its definitely modeled after one of the Wars between the Ottomans and the Greeks.

Threadmarks

View all 100 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 93: Mr. Smith goes to Athens Part 94: Twilight of the Lion King Part 95: The Coburg Love Affair Chapter 96: The End of the Beginning Chapter 97: A King of Marble Chapter 98: Kleptocracy Chapter 99: Captains of Industry Chapter 100: The Balkan League

Share: