You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

What if Jerusalem had assented to the 1538 Sanhedrin.

- Thread starter jacob ningen

- Start date

ENCORE 1807

ENCORE

1807

1807

The second Grand Sanhedrin of Paris, thought Rabbi David Sinzheim, had gone much more smoothly than the first.

There had been none of the hasty planning and haphazard selection of delegates that had happened the first time – the Emperor had instructed Sinzheim to begin preparing months before the peace of Tilsit was signed, and the delegates from France and what was now the Kingdom of Italy had been proposed by the new consistories and vetted by the Central Consistory in the Marais. And the foreign delegates, those from the German states, the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, and the few from the Kingdom of Naples, had been picked by the Emperor’s intendants in those countries, and those officials had chosen men who wouldn’t cause trouble.

Nor had there been any contentious debate this time around – in truth, the second Paris Sanhedrin hadn’t been called to debate, only to ratify. The resolutions of the 1805 Sanhedrin had, by acclamation recorded as a unanimous vote, been made applicable throughout Warsaw, the German Confederation, and all of Italy save the papal territories. And the delegates in France and Italy had ratified a constitution that included the institutions that the Interior Ministry and Sinzheim’s advisory committee had built – the consistories, a nationwide system of Jewish primary schools, a rabbinical academy in Paris, and a tax to pay for them all.

“And now it’s done,” he said to Abraham Furtado, who hadn’t been a member of the Sanhedrin this time but who had followed the proceedings in his new post at the Interior Ministry. The two were on the bank of the Seine, enjoying the last evening of what both expected to be their last Sanhedrin. The delegates would be dismissed on the morrow with the Emperor’s thanks, and there wouldn’t be another Sanhedrin in Paris unless the Emperor or a unanimous vote of the consistories summoned one.

“Except in Holland,” Furtado answered, and both men responded with something that was part laugh and part grimace. The Dutch Jews hadn’t come to Paris; instead, Carel Asser had secured an opinion from a panel of Amsterdam judges holding that, since the Dutch Jews had progressed longest and farthest toward emancipation, they didn’t need the supervision of a Sanhedrin and were capable of observing the duties of citizens out of their own conscience. Had this happened in France, Bonaparte would have quashed it soon enough, but even though the Batavian Republic had become the Kingdom of Holland, it retained enough independence that doing so would be more trouble than it was worth.

“Asser found a pen mightier than his sword – not that this was a difficult task.”

“The Emperor isn’t what anyone would call happy about it, but he won’t interfere as long as the Dutch Jews are loyal. And they are.”

Sinzheim nodded in agreement. Bonaparte certainly had his ideas of what the Jews were to become, but he was nothing if not a pragmatist, and he valued loyalty above all else. Even in France, he’d shown a far lighter hand toward the patriotic Bonapartist Jews of Aquitaine – of which Furtado was one – than those of the Bas-Rhin and Alsace. And the Alsatian Jews’ loyalty, too, had been rewarded; was not Sinzheim now Chief Rabbi of France, and would the new taxes and subsidies not enable them to build their synagogues and schools beyond anything they’d been able to do before?

Some, he knew – and he thought of Rabbi Shneur Zalman, far away in Russia – thought the Jews of France had made a bargain with the devil. It was a bargain, true. But Sinzheim would make it serve God.

_______

Sukkot came late to Lyady in 5568, and it came with freezing winds and rain from the north. Rabbi Shneur Zalman had met it bravely, wearing a scarf and gloves with his heavy coat and leading his people to the festive meal. But long before midnight, as the rain turned to sleet and the cold bit harder, even he had to invoke the Shulhan Arukh and return to the synagogue where the walls kept out the wind and there was a welcoming fire.

Inside, the women gathered in the kitchen where it was warmest; the men went to the sanctuary, spread their coats out to dry, and crowded close to the fire to pray and tell stories. Many of the stories this year were of war. The men who attended Shneur Zalman’s court at Lyady had been the core of the Hasidic regiment he’d recruited, and they spoke of distant towns, battles, the hardships of the march, their sorrow for the dead.

These were new stories for them and Shneur Zalman both. There had been war and massacre in plenty in this part of the world, and there had been many martyrs among the Jews in the Deluge and its aftermath, but it had been a very long time since the Jews of these lands had taken part in a war as soldiers. War hadn’t come to these men in the form of raiders descending on a village to kill and burn; they’d gone to it, and they’d held the guns.

Rabbi Shneur Zalman had rarely thought of war. What was it to him – the poetry of Samuel ha-Nagid, who’d led armies in long-ago Spain,, or ibn Gabirol, who had said that valor was a virtue of the hands? The sefira of Netzach, eternity, which also meant victory – was war a thing eternal? Or was it Gevurah – strength and discipline, the strong arm of Adam Kadmon? Or was it simply the grim rule of necessity?

From the stories the men told, he suspected it was mostly the last. Perhaps there was a reason why, though many stories were told of the ancient Jewish wars, few of them spoke of what happened during the battles.

He had learned about battles, this first night of Sukkot. And he would learn more of them, because he had received a letter from St. Petersburg that morning.

He’d known that something like it would come – he’d known since Prince Gorchakov had visited in late summer, uncomfortable at being among Christ-killing Zhids but man enough to pay respect to those who’d saved his life on the battlefield. The prince had said he would speak for the Chabad regiment at court, that he would see they were suitably rewarded. That hadn’t happened immediately, but it seemed that Napoleon’s second Sanhedrin had made the matter more urgent; if Napoleon intended to mobilize the Jews of all Europe, then the Tsar needed to reward those who’d mobilized for him instead.

Shneur Zalman had the letter in his hand now, and he let his eyes fall to it as the men, drowsy with wine and reluctant to face the cold, began finding space on the synagogue floor to sleep. He read the terms again: ownership of the village of Lyady, the rank of podporuchik, the right to raise a regiment, the right to bear arms in Lyady and within two versts in any direction, taxes to be remitted by one third in peacetime and altogether when the regiment was under arms for war…

Not what is given to the Cossacks, or even the Tatars of Kazan when they serve in the Tsar’s wars. But Cossacks and Tatars weren’t condemned as Christ-killers by the Church, and it was extraordinary for the Tsar to concede even this much to those who were.

He could still refuse, and some of the stories his men had told made him wonder if he should. But the Rambam had said that wars of self-defense must be fought, and surely a war against Napoleon’s godlessness was a war in defense of Judaism. He imagined the doctrines of the Paris Sanhedrin being imposed on the Jews of Russia by a victorious Bonaparte – yes, it was necessary to fight against that.

As the Jews of the Galilee had fought Napoleon, so too would the Hasidim.

_______

Chanukah, too, came late – so late that the first candles were lit on Christmas day, and so late that the seventh night, the beginning of the month of Tevet, fell on the eve of the Christians’ new year. And in Tzfat, Rosh Hodesh Tevet was also Eid al-Banat, the holiday of the daughters.

A family from Djerba had come to Tzfat thirty years before, bringing Eid al-Banat with them, and that family’s older daughter had become the childhood nurse of Dalia Zemach. The Zemach women – Dalia, her mother and grandmother, her sisters and aunts and cousins – had made Rosh Hodesh Tevet into a family celebration, and when Dalia had become nagidah of the Galilee, she’d made the celebration public.

It had been a show of strength that year, when she was just twenty, new to the governorship, and her authority was uncertain. Judith and Hannah and the high priest’s daughter were honored at Eid al-Banat, so that night was a chance for the nagidah to associate herself with their stories, to remind the people that a woman could protect the nation and the faith.

That had been seven years ago; now, Dalia was twenty-seven, three times a mother, and the unquestioned civil ruler of the Galilee. She still made Eid al-Banat a public event; if anything, it had grown to include many Muslim women and even some of the Christians. The point she had made that first year was still worth making; some had taken to calling the seventh night of Chanukah yom ha-nagidah, and strangely enough, she didn’t discourage them.

December in Tzfat this year was unseasonably mild and Eid al-Banat had grown beyond the old Zemach house by the east market, so it was held instead amid the ruins of Joseph Nasi’s palazzo. The nagidah made the announcement at midday, and at dusk, she led a procession of women up the hill to the open courtyard which was lit by a thousand eight-branched oil lamps. It was the first public meeting in that place since the tumultuous session the Sanhedrin had held after Napoleon took Jerusalem, and it was a gathering that broke tradition as much as that one had. When men met at the palazzo, it was called yarchei kallah – the months of the bride, as the ancient meetings at the Babylonian academies had been called; Dalia called this one the yarchei kallot, the gathering of all the brides.

By nightfall, there were thousands in the courtyard – from Tzfat and Tiberias, from the villages, from the outlying vineyards and farms, even from Wadi Ara and Jezreel and Acre. There was food and wine; there was singing of piyyutim, there was dancing. In Djerba, the women would have gone to the synagogue and touched the Torah, but that wasn’t the custom here, and Dalia thought it was unwise to provoke the Sanhedrin over trifles. But troupes of women did re-enact the Judith and Hannah stories – Holofernes played by a woman in men’s clothes, itself something that wouldn’t have pleased the Sanhedrin were they present – and two of the nagidah’s Muslim maids of honor told the story of Aisha. And Dalia herself climbed the ruined tower and recited from the thirty-first chapter of Proverbs before coming down to dance.

The mothers with young girls went home first, carrying their sleepy daughters down the hillside or leading them by the hand. The matrons were next, paying their respects to the nagidah and making their way home in threes and fours. The young women – the kallot and those not yet married – lasted longest, but as the church bells tolled at midnight to mark the beginning of 1808, even they departed, and Dalia and her closest companions were the only ones remaining as the lamplight guttered out and the winter stars hung overhead.

“They call this the women’s Sanhedrin,” said Naomi, the youngest of Dalia’s sisters and the only one still unmarried. “Some of the people in the city – the students, the men in the coffeehouses.”

“We lay down no law here,” answered Dalia.

“We’re making a custom. Some of the rabbis think that’s only for them to do.”

“The people make custom.” And it was true – Eid al-Banat, like Mimouna, had tested the Sanhedrin’s rules about when it was permissible for Jews in one place to follow the custom of another, and some had inveighed against both until forced to yield to their overwhelming popularity. “I think, sometimes, the Sanhedrin is afraid of it.”

“They have to live with what they fear,” said Leah Karo, a childhood friend of the nagidah and now a recording secretary at court. “Anyway, it’s the other Sanhedrin that people are talking about – the one in Paris.”

“In Paris?” asked Naomi. “They laid down no new law either…”

“But there were laymen in it.”

“There were laymen in the first one too,” said Dalia, but then it became clear to her: the presence of laymen in the first Paris Sanhedrin had gone unnoticed amid all the disputes over doctrine and Jews’ relationship with the state, but with the second one so quiescent, that had suddenly become the main thing the Galileans noticed.

“Do they want laymen in our Sanhedrin too?” Naomi said. “The rabbis would never accept that…”

“Nor the Rambam. But there have always been other councils.”

“We call it shura,” said Sahar Zuabi, another childhood friend turned court lady. “Consultation with the people.”

Dalia had read of shura. Maybe she had been part of it, the times she’d been summoned with the other vassals and governors to sit in council with the emir. There was no equivalent single concept in Jewish jurisprudence, but there were notions of consent and covenant from which it might be derived – hadn’t Rabbi Natan, for instance, described how the Exilarch was formally elected by the people and the academies even though, in practice, the office was passed from father to son? Netanel would surely know others.

The idea intrigued her – an appointed civil council, or an elected one, might form another foundation for the state, and one that might even say yes when the Sanhedrin said no. Maybe not now, but if the talk of a laymen’s tribunal continued, or could be encouraged to continue…

“I think we may want to start preparing a brief on this,” she said. “For later, of course. For later.”

Last edited:

For the record, I’m not sure whether Eid al-Banat was celebrated in the 18th century – there don’t seem to be any definitive sources about how old it is. However, there are rabbinical sources for Rosh Hodesh being a women’s holiday even in much earlier times, and Sapir Shans argues persuasively (at least I think it’s persuasive) that there are reasons for Rosh Hodesh Tevet, where a full Hallel is recited and which falls during a holiday that features several prominent women, to become the most important one. The holiday having a Judeo-Arabic name (the Hebraization “Chag ha-Banot” came later) also points to it being older. So I’m assuming that Eid al-Banat did exist in 18th-century Tunisia and that immigrants from Djerba could indeed have brought it to the Galilee Yishuv.

Anyway, the Sanhedrins of Paris and the Tsar’s concordat with Chabad have now solidified the last two of the models which will shape the relationship ITTL between Jews and the modern state. There are six in total: full-on assimilationism (espoused by radical reformers such as Friedländer); co-optation by the state in exchange for emancipation (Napoleonic Europe); loosely-organized communities with citizenship based on individual liberty (UK, US, Netherlands, Acre); a more privileged ghetto of the sort that Salo Baron thought we should have gone for (the Hasidim of Russia); autonomy within a semi-independent national home (the Galilee Yishuv); and the feudal “moshavim” of the Wadi Ara, which have by now spread to the Jezreel Valley and parts of the coastal plain. And on the seventh model, they rested.

The Napoleonic arc will now jump to 1810, and the final part of it will show these models evolving and playing out.

Anyway, the Sanhedrins of Paris and the Tsar’s concordat with Chabad have now solidified the last two of the models which will shape the relationship ITTL between Jews and the modern state. There are six in total: full-on assimilationism (espoused by radical reformers such as Friedländer); co-optation by the state in exchange for emancipation (Napoleonic Europe); loosely-organized communities with citizenship based on individual liberty (UK, US, Netherlands, Acre); a more privileged ghetto of the sort that Salo Baron thought we should have gone for (the Hasidim of Russia); autonomy within a semi-independent national home (the Galilee Yishuv); and the feudal “moshavim” of the Wadi Ara, which have by now spread to the Jezreel Valley and parts of the coastal plain. And on the seventh model, they rested.

The Napoleonic arc will now jump to 1810, and the final part of it will show these models evolving and playing out.

Last edited:

Fantastic episode! The Galilee Haskalah is shaping up to be incredibly interesting with this idea of using rule-by-consensus and consultation to bypass the Galilee Sanhedrin.

Question: what does education look like in the Yishuv? IIRC, Judaism mandates universal male literacy - is this upheld in the Yishuv? Are there formal schools beyond the religious academies? And how does education differ between the three legs of the Yishuv - Acre, the eastern Galilee autonomy and the pseudo-Moshavim?

Question: what does education look like in the Yishuv? IIRC, Judaism mandates universal male literacy - is this upheld in the Yishuv? Are there formal schools beyond the religious academies? And how does education differ between the three legs of the Yishuv - Acre, the eastern Galilee autonomy and the pseudo-Moshavim?

the perennial question in cultural history how old outside references is a custom holiday interpretation or trope. I think yiftachs daughter fits better with tu b'av but thats a minor quibble and is falsified by maghrebi practiceFor the record, I’m not sure whether Eid al-Banat was celebrated in the 18th century – there don’t seem to be any definitive sources about how old it is. However, there are rabbinical sources for Rosh Hodesh being a women’s holiday even in much earlier times, and Sapir Shans argues persuasively (at least I think it’s persuasive) that there are reasons for Rosh Hodesh Tevet, where a full Hallel is recited and which falls during a holiday that features several prominent women, to become the most important one. The holiday having a Judeo-Arabic name (the Hebraization “Chag ha-Banot” came later) also points to it being older. So I’m assuming that Eid ha-Banot did exist in 18th-century Tunisia and that immigr.

love thisAnd on the seventh model, they rested.

Last edited:

Not to bypass so much as to create a counterweight - the Sanhedrin has legitimacy of its own and can't simply be ignored, but an advisory council (which is what it would be at first) would be a source of civil policy that doesn't depend on the nagid's personal authority. The past generations of Zemachs didn't worry much about that, but a young woman suddenly exercising what is traditionally a man's power certainly would. She's not dumb and she realizes that such a council could eventually be a counterweight to her office, but right now, strengthening the civil state is more important.Fantastic episode! The Galilee Haskalah is shaping up to be incredibly interesting with this idea of using rule-by-consensus and consultation to bypass the Galilee Sanhedrin.

The Yishuv does honor the mandate - early in this thread, I mentioned that one of the first things the Sanhedrin did was set up primary schools. They're Talmud Torah-type schools, but they've resulted in a great majority of males being literate (about half the women too, but they're usually taught at home). There are also a few schools not run by the Sanhedrin that give more attention to secular subjects; these schools are influenced by the Haskalah and the kollel katan of Acre, which has its own school system in that city. The pseudo-moshavim are smaller communities of under a thousand, so each maintains a village school.Question: what does education look like in the Yishuv? IIRC, Judaism mandates universal male literacy - is this upheld in the Yishuv? Are there formal schools beyond the religious academies? And how does education differ between the three legs of the Yishuv - Acre, the eastern Galilee autonomy and the pseudo-Moshavim?

Especially where the custom exists among people who the chroniclers see as beneath their notice, in this case women. OTOH, that isn't likely to happen ITTL now that Eid al-Banat has become an opportune public holiday that some people travel two days to attend.the perennial question in cultural history how old outside references is a custom holiday interpretation or trope.

Also, Yiftach's daughter probably isn't a story that a reigning nagidah (as you can see, the dynasty of beys/nagids has steadily adopted more of the trappings of monarchy) would want to associate with herself.I think yiftachs daughter fits better with tu b'av but thats a minor quibble and is falsified by maghrebi practice

Last edited:

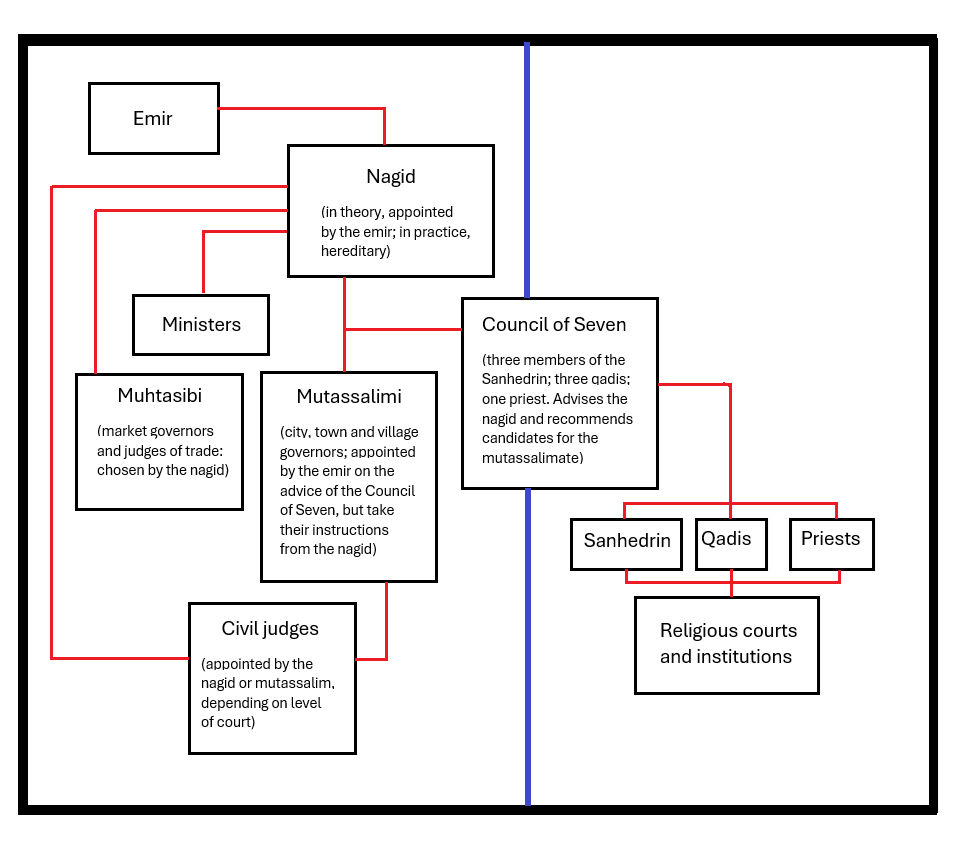

Also, since we're talking about government, the below is more or less how the eastern Galilee works in the early 19th century. Left side of the blue line is civil, right side is religious. Again, you can't expect any governmental arrangements in this time and place to be neat and tidy, especially since these institutions developed on an ad hoc basis over a period of more than 250 years. Rank in the chart isn't necessarily indicative of how much power an institution has; the Sanhedrin is more powerful on a day-to-day basis than the Council of Seven, which meets only once or twice a year and which has no courts or other institutions that report directly to it.

how are the members of the council selected? and has it always had the same composition?Also, since we're talking about government, the below is more or less how the eastern Galilee works in the early 19th century. Left side of the blue line is civil, right side is religious. Again, you can't expect any governmental arrangements in this time and place to be neat and tidy, especially since these institutions developed on an ad hoc basis over a period of more than 250 years. Rank in the chart isn't necessarily indicative of how much power an institution has; the Sanhedrin is more powerful on a day-to-day basis than the Council of Seven, which meets only once or twice a year and which has no courts or other institutions that report directly to it.

It's descended from the emergency council that took over after Reina Nasi died childless and that was the highest local authority between the fall of Fakhr al-Din II and the rise of Zahir al-Umar. It has always had three rabbis, three qadis and a priest, but the composition hasn't always been the same. Currently, and for the past hundred years or so, the rabbinical members are the Nasi, the Av Bet Din, and the oldest member of the Sanhedrin (although a proxy is sometimes appointed if the last-named is physically or cognitively incapable); the qadis include the Chief Qadi of Tzfat, the Chief Qadi of Tiberias, and a third one chosen by them who has nearly always been a qualified mufti; and the priest is agreed on by the rabbis and qadis.how are the members of the council selected? and has it always had the same composition?

The priest is where it gets tricky - the rabbis and qadis try to appoint one who all the churches respect, but that isn't always possible, and they need to rotate between sects every few sessions to avoid the appearance of favoritism. There are also issues with the Druze being left out. They're a small minority and it made sense to not include them when Fakhr al-Din was the regional overlord, but without him as patron, many of them feel they don't have a voice. The informal way this has been dealt with is that the nagid always has at least one Druze cabinet minister - usually the sheikh who controls Nabi Shuʿayb - who then acts as "court Druze," but there's a push to include them more formally. This may another problem the nagidah hopes to rectify with an advisory council; we'll see more in one of the forthcoming updates.

i presume you mean the oldest besides the av bet din or nasi if they are the oldest.It's descended from the emergency council that took over after Reina Nasi died childless and that was the highest local authority between the fall of Fakhr al-Din II and the rise of Zahir al-Umar. It has always had three rabbis, three qadis and a priest, but the composition hasn't always been the same. Currently, and for the past hundred years or so, the rabbinical members are the Nasi, the Av Bet Din, and the oldest member of the Sanhedrin (although a proxy is sometimes appointed if the last-named is physically or cognitively incapable); the qadis include the Chief Qadi of Tzfat, the Chief Qadi of Tiberias, and a third one chosen by them who has nearly always been a qualified mufti; and the priest is agreed on by the rabbis and qadis.

The priest is where it gets tricky - the rabbis and qadis try to appoint one who all the churches respect, but that isn't always possible, and they need to rotate between sects every few sessions to avoid the appearance of favoritism. There are also issues with the Druze being left out. They're a small minority and it made sense to not include them when Fakhr al-Din was the regional overlord, but without him as patron, many of them feel they don't have a voice. The informal way this has been dealt with is that the nagid always has at least one Druze cabinet minister - usually the sheikh who controls Nabi Shuʿayb - who then acts as "court Druze," but there's a push to include them more formally. This may another problem the nagidah hopes to rectify with an advisory council; we'll see more in one of the forthcoming updates.

Yes, if the Nasi and/or the Av Bet Din are the oldest members of the Sanhedrin at any given time, then the next oldest after them is chosen. You'd expect a lot of turnover in the oldest-member slot, and there often is, but a remarkable number of rabbis in Ottoman Palestine IOTL seem to have lived into their eighties or even nineties.i presume you mean the oldest besides the av bet din or nasi if they are the oldest.

For those who've asked about America, here's the main character of the forthcoming 1810 story, and here's a member of the supporting cast.

Last edited:

The question is... will these measures that are apparently improving the status of Jews vis-à-vis their host nations remain permanent IITL?Anyway, the Sanhedrins of Paris and the Tsar’s concordat with Chabad have now solidified the last two of the models which will shape the relationship ITTL between Jews and the modern state. There are six in total: full-on assimilationism (espoused by radical reformers such as Friedländer); co-optation by the state in exchange for emancipation (Napoleonic Europe); loosely-organized communities with citizenship based on individual liberty (UK, US, Netherlands, Acre); a more privileged ghetto of the sort that Salo Baron thought we should have gone for (the Hasidim of Russia); autonomy within a semi-independent national home (the Galilee Yishuv); and the feudal “moshavim” of the Wadi Ara, which have by now spread to the Jezreel Valley and parts of the coastal plain. And on the seventh model, they rested.

Or, on the contrary, will Napoleonic emancipation in non-French lands and the tsarist "Cossackization" of the Chabadniks be reversed after the ultimate defeat of the Corsican?

I have doubts about how long this sudden fondness for Zhids can last at the Russian court ( it'll probably last until they are no longer considered usefull). If all these gains are erased overnight... well, there is a place where many Jews now disenfranchised and deprived of semi-statehood would fit...

Last edited:

OTL many of the Germans states rolled back the Napoleonic emancipation.The question is... will these measures that are apparently improving the status of Jews vis-à-vis their host nations remain permanent IITL?

Or, on the contrary, will Napoleonic emancipation in non-French lands and the tsarist "Cossackization" of the Chabadniks be reversed after the ultimate defeat of the Corsican?

I have doubts about how long this sudden fondness for Zhids can last at the Russian court (well, it'll last until they are no longer considered usefull). If all these gains are erased overnight... well, there is a place where many Jews now disenfranchised and deprived of semi-statehood would fit...

Or, on the contrary, will Napoleonic emancipation in non-French lands and the tsarist "Cossackization" of the Chabadniks be reversed after the ultimate defeat of the Corsican?

I believe some of the Italian states did too - certainly Rome. And in the German states that didn't roll back emancipation, there was a backlash that led to incidents like the Hep Hep riots. The post-Napoleonic period ITTL will be similar, maybe even more so, given that the Duchy of Warsaw wasn't part of the Napoleonic emancipation IOTL but is more so ITTL - emancipation of Jews in Poland at this time was unpopular, and the postwar reaction to even partial reforms will be strong.OTL many of the Germans states rolled back the Napoleonic emancipation.

In Russia - well, at this point in the story, the Tsar's court distinguishes between good and bad Jews, and that rarely ends well. It's possible that Jews might end up fleeing from other Jews, which isn't unprecedented IOTL but could happen at scale. And as you say, the favor shown to the Tsarist Hasidic sects may not last forever, especially in an absolute monarchy where a change of Tsar means a change of policy. "Now a new Tsar arose over Russia, who knew not Rabbi Shneur Zalman..."

The flip side is that, should a pogrom occur, the Hasidim will be much better armed to resist it. But they're heavily outnumbered, so that would only go so far.

There are several such places, but yes, that's one of them.I have doubts about how long this sudden fondness for Zhids can last at the Russian court ( it'll probably last until they are no longer considered usefull). If all these gains are erased overnight... well, there is a place where many Jews now disenfranchised and deprived of semi-statehood would fit...

Last edited:

And, as you mentioned before, there is a war around the corner that could make additional manpower (especially in the form of well-trained war veterans) very useful for the Banu Zaydan....

and we're seeing martial jews a century before Jabotinsky and arising not out of romanticized notions of warriors and the Hasmoneans but sheer emancipation and being drafted.And, as you mentioned before, there is a war around the corner that could make additional manpower (especially in the form of well-trained war veterans) very useful for the Banu Zaydan....

And, as you mentioned before, there is a war around the corner that could make additional manpower (especially in the form of well-trained war veterans) very useful for the Banu Zaydan....

That, plus 250 years of the Galilee Yishuv having to defend its towns and fight in the regional overlords' wars. But what you said about romanticism is an important point - these Jews are martial, but as Aharon Zemach mentioned in his inner monologue at Mount Tabor, they don't have a warrior culture like Jabotinsky tried to inculcate. They have their war stories and heroes, and they might end up with a concept of "patriotic war" similar to Russia's, but they still think of war fundamentally as something they do when they have to. Romanticism leads to glorification of war; service in conscript armies and fighting wars of necessity generally doesn't.and we're seeing martial jews a century before Jabotinsky and arising not out of romanticized notions of warriors and the Hasmoneans but sheer emancipation and being drafted.

One historical precedent I don't think I've mentioned yet is the Jewish community of Finland, which was founded IOTL (and possibly ITTL) by cantonist soldiers who were drafted as young boys and settled in Helsinki after serving long hitches there. Helsinki was outside the Pale, so only those who had the privileges of military veterans could live there, meaning that AFAIK it's the only modern Jewish community whose origin was primarily military. And the Finnish Jews' participation in both WW1 and WW2 was high [1], but when I was there in the 1990s and met several WW2 veterans as part of the advance work for an article that never got published [2], they all had a very matter-of-fact view of war. Being descended from conscripts drafted at age 12 will do that. I suspect the Yishuv will have a similar outlook.

[1] Not to mention historically ironic, given that Stalin's invasion of Finland put the Finnish army, including the Jewish soldiers, on the same side of the war as Nazi Germany. I personally met a Jewish army nurse in Turku who was awarded the Iron Cross. Yes, that Iron Cross.

[2] I also visited the old Russian fort in Helsinki harbor the day after I had one of the meetings, and I had the place to myself. It's in ruins now, but I could imagine walking those ramparts as a cantonist, counting the months until I could muster out, and thinking that whatever shetl I was born in, this was home now. Yeah, some of the ideas that are going into this story have been in my mind for a very long time.

Its also related to my theory of why Tolkien and Disney are popular in America or the royals because the US doesnt have a monarchy.That, plus 250 years of the Galilee Yishuv having to defend its towns and fight in the regional overlords' wars. But what you said about romanticism is an important point - these Jews are martial, but as Aharon Zemach mentioned in his inner monologue at Mount Tabor, they don't have a warrior culture like Jabotinsky tried to inculcate. They have their war stories and heroes, and they might end up with a concept of "patriotic war" similar to Russia's, but they still think of war fundamentally as something they do when they have to. Romanticism leads to glorification of war; service in conscript armies and fighting wars of necessity generally doesn't.

PHILADELPHIA FREEDOM NOVEMBER 1810

PHILADELPHIA FREEDOM

NOVEMBER 1810

NOVEMBER 1810

There were times when Rebecca Gratz needed an escape from charity work and assembly balls and a houseful of family – she loved all these things, but there were times. And at those times, the chambers of the Port Folio magazine were a good place to go. There were books in those chambers, and people who liked to talk about books. There was usually tea on the boil. There were tables where Rebecca could sit and read or listen to one of the regulars read from a work in progress – on rare occasions, she’d shared her own poetry, although she’d never been so daring as to publish any. And there was a sense of a wider world than the cobblestone streets outside.

It was ten o’clock on a mild November morning, an Indian-summer morning with a breeze stirring the fallen leaves, and several of the regulars were already there. Dennie, the editor, who’d finally abandoned his ridiculous Oliver Oldschool pen name, was at the desk by the far wall; Saunter and Biddle, two of his stable of writers, were deep in conversation at one of the tables, tea forgotten as Biddle shook a bundle of papers at Saunter and ran down all the reasons why he should tear up his story. Charles Ingersoll, a year younger than Rebecca and back from Europe, looked on in amusement; then he saw Rebecca, smiled in greeting, and tapped his fingers on another bundle.

That was another thing about the Port Folio – it was a place where Rebecca could get mail without the risk that her sisters would read it first. And it seemed that today, she had quite a bit of it.

“We’d have known these were yours even if your name hadn’t been on them,” said Ingersoll, and one look at the stack of letters told Rebecca why. The envelopes bearing addresses in London and Paris and Frankfurt weren’t unusual, but under them was a month-old copy of The Israelite magazine and two-month-old newspapers from Acre and Tzfat, and all of them were in Hebrew.

Rebecca sat across from Ingersoll and began to read. Five years ago, she hadn’t known Hebrew; it wasn’t commonly taught to girls in Philadelphia, and the rabbi at Congregation Mikveh Israel continued his predecessor’s practice of delivering sermons in English. But one of her correspondents in London, the salon-keeper Rachel Levien Cohen, had told her she needed to learn it if she wanted to appreciate what was happening in the Jewish literature of the Holy Land and Europe. It had taken her long to learn, and the Hebrew of Acre and Tzfat, with its borrowings from Arabic and Syriac and Yiddish and Spanish and its spelling conventions expanded to include sounds that existed in those languages but not in biblical Hebrew, could still sometimes confound her. But Cohen had been right; the language had opened a world.

By now, Dennie had noticed her presence and looked up from his desk with interest. “Anything good?” he asked. He sometimes asked Rebecca to translate Hebrew stories for the magazine – they were something different, he said, something that his more jaded readers would find entertaining. If the letters that came in from New York and Boston were anything to go by, some of them did.

“Not this,” Rebecca answered. “One of the contractors digging sewers in Tzfat stole two thousand piasters, and both the civil courts and the Sanhedrin have brought charges…”

“No shortage of stories like that here,” said Ingersoll, “though I don’t think I’d be welcome practicing before your Sanhedrin.” He was a lawyer and diplomat, well-traveled, with years at the Philadelphia bar despite his youth, but from what he’d gleaned of the Sanhedrin, he thought them passing strange. Rebecca wasn’t sure she disagreed.

“This, though,” she said – her eyes had fallen on another article in the Acre newspaper, this one a work of fiction. “A Mahometan who venerates a Jewish holy man and his Jewish neighbor who admires a saintly imam – in a hard winter, they pray for miracles for each other.”

“Do they do that over there?” asked Saunter, his attention drawn. “Venerate each other’s saints?”

“I’ve read of such things before. The Sanhedrin takes a dim view of it and, I suspect, so do the Mahometans’ judges. But I wouldn’t discount anything.” She raised her teacup to her lips and, echoing her thought of a moment before, added, “they’re strange over there.”

Now that she’d thought of it, she realized that she’d heard versions of that quite often. Her correspondents had told her that there had been an upturn recently in traffic between Europe and the Holy Land; with Europe at peace outside the battlefields of Spain and Portugal, the Jews of Napoleon’s empire – the well-off ones, at any rate – had created their own version of the Grand Tour. Visit Rashi’s grave (or at least the place where it was reputed to be), attend a lecture at the new Hebrew Academy in Paris, see the old synagogues of Provence and Italy – and thence to Salonika and Konstantiniyye and Acre and Tzfat and Tiberias before finishing in Jerusalem. And many of those who’d taken the tour had described the Jews of Palestine the same way – they’re strange over there.

And, she’d seen, the feeling was often mutual. Another of the stories in the Acre paper was a lampoon of a Dutch Jew taking exactly that tour and doing outrageous things at each way-station. He was obviously intended to be a caricature of someone – Rebecca didn’t know who – but it might not be far off how the Acre Jews looked on many of his compatriots.

That story would be too esoteric by far for an American audience. But the one about the Jewish and Muslim saints might amuse them. “Should I translate it?” she asked.

“I think so, yes,” said Dennie. “Can you have it done next week? I’ll have space for it the week after, if so.”

Rebecca mentally ran though a list of social engagements and nodded. She put the Acre newspaper down and opened The Israelite – printed in Bordeaux by the maskilim of Aquitaine, and in a pure Hebrew that Rebecca recognized from the songs the men sang at Mikveh Israel – but Ingersoll, who’d come with the teapot to refill her cup, put his other hand on the magazine before hers reached it.

“Always translating, Rebecca,” he said. “I like hearing those stories, but you have your own to tell, no? It’s been too long since we’ve heard one of your poems. They belong here. Maybe they belong more in an American magazine than the work of someone half a world away.”

“My poems are just scribblings,” said Rebecca, embarrassed. “They aren’t any good…”

“Neither are Saunter’s stories, and our Mr. Oldschool publishes at least one of them a month. And your work is better than you give it credit for.”

“Who would be interested in a woman’s scratchings?”

“Should someone have told that to Miss Wheatley?” Ingersoll said. Damn it, he knows me too well; it had been the volume of Wheatley’s poems, read when she was fifteen, that had turned Rebecca decisively against slavery.

“Say you’ll think about it,” he said; she agreed, put more honey in her tea, and began translating.

_______

That afternoon belonged to the Female Association for the Relief of Women and Children in Reduced Circumstances, delivering food and necessities to impoverished widows of the Revolution. As she often did, Rebecca made her rounds with Hannah Levy, a childhood friend and a co-founder of the society, walking out of the city to the shanties on the outskirts where many of the widows lived and the farms along the Schuylkill where others did. Later, at sunset, Hannah came home with her for supper.

Rebecca’s father wasn’t well enough to join the family table; that happened about half the time now, and though it had become a familiar pain, it was a pain nevertheless. Her mother was there, though, and her unmarried sisters and brothers; so were Hannah’s father Moses, who’d been elected city recorder, and Jacob Cohen, the rabbi at Mikveh Israel.

It was an American meal – a roast from the kosher butcher on Sterling Alley, bread from the oven, roasted carrots and parsnips, apple preserves from some of the very farms Rebecca had visited earlier in the day. The conversation around the table, too, was American – maritime trade, the Gratzes’ growing business interests in the West, the affairs of the city and nation. But inevitably it turned to other matters, and long before the meal was done, Rebecca regaled the others with the stories she’d read in the Acre newspaper.

Cohen, to her surprise, found the Grand Tour story the funnier of the two. “That’s Asser to the life, and it’s about time someone took him down a peg,” he said. “But I doubt he’d ever take that tour. Amsterdam is his Jerusalem; he doesn’t need the other one.”

“Do you think more of us should?” Rebecca asked. She’d never thought of going to the Holy Land before, but some of her thoughts that morning returned to her. “It seems sometimes that Jews in different places are becoming strangers to each other.”

“We always were,” answered Levy, “or do you think you’d have found Turkey or Yemen familiar a hundred years ago? It’s the opposite that’s happening – all of us scattered across the world are getting to know each other again, making something new of it all. In Palestine, in Europe, in America… we should worry less about becoming strangers to each other than becoming strangers to ourselves.”

“What does that mean?” asked Hannah, and Rebecca echoed the thought; Levy’s words themselves seemed strange at a table crowded with family and with friends who were almost as close.

“I think I may know,” said Rebecca’s mother Miriam. “There are just a few of us here, and we’re free, which is a good thing, but it means we’re free to be as Jewish as we want to be…”

“As much,” said Levy, “or as little.”

For a moment, Rebecca resisted the thought – she knew, from her correspondence, that there were no shortage of assimilated Jews in other countries – but she also understood; there was no Sanhedrin here, no consistories, no kehillot, none of the things that ensured that even Jews who were lax in their observance would remain part of the community.

Surely a grand tour wasn’t the answer to that – how many in America could even make such a long and perilous journey? A school, maybe? That was certainly a thought for later, but for now… an American Jewish magazine? A place to share learning and stories, to prevent those stories from becoming strange, maybe to make something new as the Jews of Europe and the Holy Land were doing? One or another of the Port Folio regulars – Ingersoll’s image came to mind, and she flushed – would know how to get that started.

And maybe it would also help if we shared some of those stories with our neighbors, she thought. After supper, she’d have to search through the desk drawers upstairs and find where that poem was.

Last edited:

Share: