Despite the difficult winter, 1862 seemed to be a bright year for the Union cause. The news of Grant’s great victory over Forts Henry and Donelson had raised Union morale. Everyone believed that a final push was all that was needed for the Confederates to be driven out of Washington. Afterwards, “it’s just a question of marching and licking the rebels”, as an overconfident soldier said. Many recognized that the war would not be over even if McDowell’s campaign succeeded beyond their greatest expectations. But a “sanguine trust in victory” had taken hold of the people. Singing battle songs and cheering, McDowell’s troops marched forward in January 30th, hoping to equal and surpass Grant’s achievements in the west.

On the Confederate side, gloom and despair seemed to rule the day. Breckinridge, known for his oratory, tried to rally his people. Before a Richmond crowd, he talked of the gallant Southern soldiers and his trust in eventual victory. A man shouted then: “Liar! The truth will prevail!” “The truth will prevail,” Breckinridge agreed, “You may smother it for a time beneath the passions and prejudices of men, but those passions and prejudices will subside; and the truth will reappear as the rock reappears above the receding tide. I believe this cruel war will end, and our Confederacy will walk by the light of the sacred principles upon which she was founded. Bright and fixed, as the rock-built lighthouse in the stormy sea, they will abide, a perpetual beacon, to attract the political mariner to the harbor of liberty and peace."

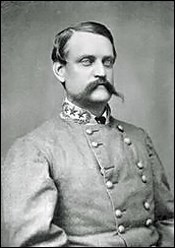

But privately, Breckinridge was also expressing doubts about the future of his Confederacy. In many ways, Breckinridge led a life similar to Lincoln’s, but in each crucial crossroads they had chosen opposite paths. Both came from immigrant families that sought Virginia for a new life, and later migrated to the bluegrass of Kentucky. But while Lincoln felt disinterested on and perhaps a little shamed for the history of his plebian family, Breckinridge was proud to come from a legacy of important men. Lincoln’s father had led Kentucky for Indiana, and later Lincoln himself made a life for himself in Illinois. Breckinridge’s family remained one of Kentucky’s most important ones, and though he also lived for some time in Iowa, Breckinridge eventually returned home. Lincoln was largely a self-made man who gravitated towards the Whigs; Breckinridge had the help of his family, and he was a “glorious Democrat.”

Lincoln achieved relatively scarce success before his nomination as a dark-horse. Breckinridge was a very prominent Democrat, and his nomination was assured from the start. Lastly, Lincoln had chosen to fight for the Union, while Breckinridge chose to side with the South, with rebellion, and slavery. The choice was a painful one, and like with many other Confederates, Breckinridge was ultimately compelled due to personal honor and a sense of duty.

He did not believe secession to be justified, but sincerely thought that states had a right to secede because “the election of a foe to a state’s rights ends the Federative system; all the delegated powers revert.” He was a true moderate, and he fervently wanted to preserve the Union. Just like many Northern moderates voted for Lincoln because there was no better option, many Southern fire-eaters voted for Breckinridge because he was the only option. Though Breckinridge was the candidate of the South, he was not the candidate of the Slavocrats.

Just like moderates had accused him of being a secessionist previous to the actual secession crisis, Southerners accused Breckinridge of being a free-soiler who did not care about protecting slavery. Many were having second thought about his election as the President of the Confederate States. His expertise, fame, moderation, and popularity were the main reasons behind his nomination and eventual victory. But it seemed that he had outlived his usefulness. Most of the Upper South was in the Confederacy, while the Border States were contested. A far cry from the promise that Breckinridge secured them for the Confederacy. Likewise, many were alienated over his handling of the war.

Breckenridge remained clean shaved before the war. After it started, he grew an impressive mustache. Here he's depicted in a Confederate general's uniform.

Like Lincoln, Breckinridge had to face a staunch opposition. Some even whispered that a challenge should be mounted for the elections of November 1861. None did, and at the end those elections only ratified Breckinridge’s position, which officially changed from provisional president to a regular one. Breckinridge’s position was not altogether disastrous. There were still high hopes on the diplomatic front, and the Confederate economy seemed to hold just fine for the moment. But nothing would matter if McDowell’s campaign was successful.

The “Western disaster” had caused “the President to lose the confidence of the country,” declared a newspaper. Many were doubtful that the young man, who didn’t even come from a state under effective Confederate control, could meet the challenge. Thomas Bragg noted that Breckinridge “seems a good deal depressed—and though he holds up bravely, it is but too evident that he is greatly troubled.”

Breckinridge was, luckily for the Confederacy, a man of administrative talent who was able to endure long work-hours and harsh criticism for the cause. His greatest sin was his love of the bottle, but he was mostly able to set it aside. He unhealthily worked until he was completely exhausted, then would sleep for long hours until some important affair demanded his attention. If left unchecked, he could sleep entire days.

When it came to criticism, he said to “the venomous men who attack me – pour on, I can endure.” Despite the lack of arms and food, Breckinridge did his best to supply the troops, who in turn started to gain affection for “Johnny Breck.” A charismatic man, Breckinridge was adept when it came to balancing the inflated egos of many Confederate politicians and military men, but he was not afraid to replace incapable officials, such as Lucius B. Northrop, though that action wounded the sensibilities of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis.

Breckinridge’s relation with Davis, not always the easiest man to get along with, is perhaps proof of his talents as a statesman. Davis was proud, humorless, and stubborn, though he also could be attentive and cordial. He did not suffer fools gladly, and lacked the tact to hide this. “In his manner and language there was just an indescribable something which offended their self-esteem and left their judgments room to find fault with him,” commented Secretary of the Navy Mallory. But Davis was also capable, and he formed a friendship with Breckinridge based on mutual respect. Similarly to Lincoln and Stanton, Davis often was tasked with rejecting the demands of politicians and generals, thus saving Breckinridge from their animosity.

Breckinridge’s trust on his generals was not as unwavering. He was really disappointed with the cautious Joe Johnston, and though he liked Beauregard better, he also had his doubts. When Albert Sydney Johnston offered to resign over his failures, Breckinridge almost accepted, but decided against it in part thanks to Davis, who told the President that “if Sidney Johnston is not a general, we had better give up the war, for we have no general.” Davis was not willing to come out to defend the other Johnston and Beauregard, and the tensions between the “triumvirate of petticoats” only served to harm the Confederate cause.

Nonetheless, just like Lincoln was developing a strategy to win the war, Breckinridge also started to rethink his own plans. Together with Secretary Davis, he concluded that it was a mistake “to attempt to defend all of the frontier, seaboard and inland.” Instead, the Confederate army would be concentrated in strategic points, the two most important theaters being, of course, Maryland and the Mississippi. Though he acknowledged that it “brings great pain to me and the country”, Breckinridge also decided that retaking Kentucky would not be a priority until “the perfidious invader is expulsed from the vital regions of the Confederacy.” He also listened attentively to the demands for action. “The people demand an advance into the enemy’s territory. Will the voice of the people again be denied?”, asked the

Richmond Enquirer.

The offensive-defensive strategy having finally crystallized into a rational doctrine, Breckinridge started to look for generals who could apply it and achieve victories. He found two officials, both from Virginia. One was a promising man, who he decided to send to North Carolina. The other had seemed to be promising, but he had failed thus far; nonetheless, Breckinridge still saw talent within him. The President, however, did not call Longstreet and Lee to Richmond yet, but he kept his eyes over them, should he need to replace Johnston and Beauregard.

The pressing issue was how to meet McDowell’s advance. Happily for Breckinridge, the Confederate Congress had followed its Union counterpart and required three-year enlistments. Otherwise, the army may have melted away. But the rebels still desperately needed men and arms. Breckinridge appealed for those resources from the states “to meet the vast accumulation of the enemy before him.” At one point, he even accepted the knives and pickets offered by Governor Brown of Georgia.

These shortcomings probably resulted in Breckinridge changing his personal convictions. He had always been a friend of internal improvements and reform, rare opinions for a Southern Democrat. But he also believed in small government and states rights. However, he started to believe that a powerful central government would be necessary if the Confederacy wanted to survive, paradoxical as that may be. Donning “the mantle of Hamilton to achieve the goals of Jefferson”, Breckinridge became the leader of a Confederate faction that supported measures such as conscription and the suspension of habeas corpus.

This last point was very contemptuous. Breckinridge had denounced Lincoln’s actions "to impair personal liberty or the freedom of speech, of thought, or of the press" by throwing people in “vile Bastilles.” But the actions of Unionist partisans in Eastern Tennessee and Texas had forced Breckinridge to throw people into Southern Bastilles as well. Worried about Unionist spies and other potential dangers to the defense of Maryland, Breckinridge suspended the writ of habeas corpus on his own authority, much like Lincoln did.

Just like in that case, there were grumblings about “military despotism” and how “it’s impossible to retain our cherished liberty if our President acts like the Philadelphia tyrant.” Breckinridge dismissed these complains, and although Congress tried to assert its authority, Breckinridge successfully convinced them that the suspension of habeas corpus was a “necessary measure to preserve the security and liberty of our country.” Fiery debate followed, until the imposing Texas Senator Louis Wigfall demanded retroactive approval of Breckinridge’s actions. “No man has any individual rights, which come into conflict with the welfare of the country,” Wigfall thundered. It was the beginning of a close relation with the administration, but also the birth of antagonistic political parties within the Confederacy.

Breckinridge, thus, also took the necessary political and military maneuvers to be ready for the next battle. As winter gave way to spring, he realized that the hour for that battle was fast coming. He accompanied Davis, who went through a religious revival as a result of the war, to Church. Breckinridge highly respected the Lord and the Church, but he was not a devout follower. Nevertheless, he prayed for victory.

On January 30th, McDowell and the Army of the Susquehanna set forth in the campaign. Their objective was Sweetser’s Bridge, near Baltimore. After Beauregard’s main force was distracted, McClellan would break out of Annapolis, forcing the rebels there to either retreat to Washington or join Beauregard, who would be trapped between McDowell’s and McClellan’s forces. If successful, the campaign would be a deadly blow to the rebellion.

Beauregard’s scouts reported the movement just hours after it had started. One of the few advantages the rebels possessed was a superior cavalry. While Union cavalry was divided in small regiments assigned to each unit, Confederate cavalry was consolidated into a unique division that was tasked with reconnaissance and protecting the flanks of the armies. They also possessed great human talent, most Southrons being able to ride better than the urban Yankees could.

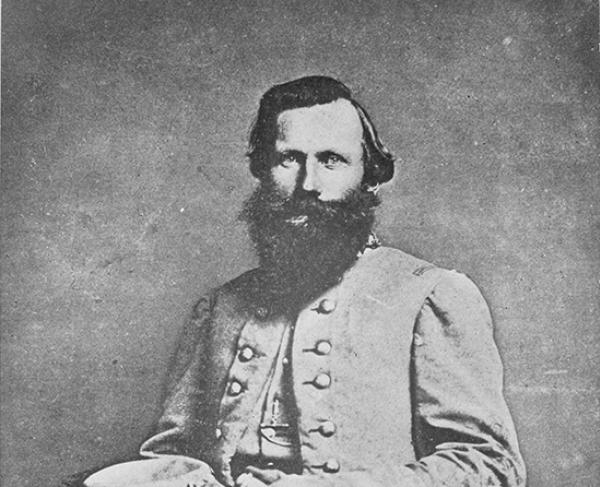

The leader of the cavalry corps was the best example of this superiority. Jeb Stuart was a gifted leader with the airs of a dashing cavalier. Clad in a shining uniform with knee-high boots and a hat with an ostrich feather, Stuart craved fame and martial glory despite his young age of 28 years. Breckinridge, whose competence was similarly questioned due to his youth, took a liking to Stuart. While most rebels were probably apprentice about facing the enemy once again, Stuart and his troopers were eager.

Johnston and Beauregard formed an informal war council to discuss the course of action. “The Bold Beauregard”, as friendly press called him, wanted to seize the initiative and cross Ellicott’s Mills. Though risky, the action could potentially force McDowell to go back to stop the enemy from invading

his territory. But the cautious Johnston was not convinced by the proposal. At the end, and after some considerable bickering, both Generals decided to simply defend until McDowell’s purpose became apparent. Their greatest fear was what McClellan could do, since he would be in their rear if he managed to break out of Annapolis.

Stonewall Jackson was tasked with stopping McDowell’s advance. A harsh disciplinarian who pushed his men as hard as he pushed himself, Jackson was also a very eccentric man. A religious fanatic who believed Yankees were the devil, Jackson was humorless and secretive. “His rule of strategy—"always mystify, mislead, and surprise the enemy"—seemed to apply to his own officers as well”, comments historian James M. McPherson. Some of his own soldiers doubted that “Old Tom Fool” could beat back the Northerners, but he proved them wrong.

Jackson contested the crossing as he was ordered, his greybacks fighting against the bluecoats valiantly. Both sides were rather sluggish in their actions at first, but eventually the Union troops started to gain enthusiasm. The edge of their attack was blunted by Jackson’s effective defense, but the Federals had a greater number of men. McDowell, however, was reluctant to commit them all to the battle until the crossing was successful. The choice was not irrational – built in a marshy area with heavy forests, the bridge was thin, and thus sending the entire force at once would not help, but cause confusion and bottlenecks. McDowell, nonetheless, can be faulted for fixating on taking the bridge, instead of fording the Patapsco elsewhere.

James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart

In any case, it seemed like the rebels would soon be forced back. Another part of the Army of the Susquehanna was further to the west, pinning down the other half of Beauregard’s force. But the burning question was one: what was McClellan doing? Indeed, though McDowell had provided a diversion, the troops at Annapolis hadn’t moved yet to escape their “corking.” The reason McClellan gave was the “overwhelming numerical superiority of the foe.”

This kind of wild exaggeration of the enemy’s strength became a consistent flaw in McClellan’s generalship. Some have blamed the head of his intelligence service, Allan Pinkerton, who often assumed that Confederate regiments were all in the same place at full strength, which obviously never happened. But McClellan’s own timidity and fear of failure also played a part. In this particular case, rebel wits also served to stall him. John B. Magruder, left with only 15,000 men to face McClellan’s 25,000, decided to stage a theater show. He had his soldiers march in circles and loudly move artillery cannons, giving the impression that he had a much larger force. McClellan took the bait, and refused to move until he could be assured that he had greater numbers than the rebels.

A distraught McDowell agreed to send some 5,000 soldiers more to McClellan, bringing his force down to 60,000, of whom half were engaged with Jackson’s 25,000 and the other half were pinning Beauregard’s 30,000 down. Dissatisfied with his inability to make McClellan act, McDowell decided to take the initiative again. But the Federal and rebel forces were almost completely equal now, and Jackson still resisted admirably. Decided to breakthrough no matter what, McDowell recalled most of the force at Ellicott’s Mills, to attack again at early the next day. The result was that Beauregard actually outnumbered the Federals there.

During the night, Jackson conferred with Beauregard. Jackson proposed a bold plan that seemed crazy, but promised a great victory if executed correctly. Believing that McClellan was bound to see through Magruder’s theatrics eventually, and that Jackson would be unable to resist much longer at the bridge, Beauregard approved the plan. Knowing that Johnston would not agree to it, he hid it from his General in-chief.

In the middle of the night, Beauregard quietly sent fresh troops towards the bridge, while Jackson and his men moved towards Ellicott’s Mills. For Jackson’s tired men, the forced march was torture, but their commander had no tolerance for human weakness. The men slept for a few hours, while the better rested Federals woke up, ready to finish the rebels. They were surprised when instead of Jackson’s equally tired Southerners, they found Beauregard’s fresh brigades. McDowell had lured Beauregard and his reinforcements out of Ellicott’s Mills, but there were no Federals there to advance and attack his flank. There weren’t any Federals to keep an eye on Jackson either.

While McDowell and Beauregard faced each other for the second time, Jackson’s Brigade, guided by a Confederate Marylander, crossed Ellicott’s Mills. After a daring forced march, these men suddenly appeared on McDowell’s right flank. At first it seemed like they were going to the village of Catonsville. McDowell detached 20,000 men to wait for the 15,000 Jackson had. But some 7,000 thousand rebels suddenly changed direction and went North to Franklin. Splitting on the face of a superior enemy so far away from their base of operations seemed insane, so the Union commander believed it was a trap and sent only 10,000 men to go for them. The other half of the force remained in Catonsville like a sitting duck.

At Franklin, Jackson quickly forded the small stream and waited for the Federals, who launched piecemeal attacks that he repealed easily. Then his rebels went forward with a mighty yell, scattering the Federals, who retreated back to Baltimore. Then he returned to Catonsville, reunited his force, and defeated the Union force there, which in turn fled

west toward Frederick. Thus, Jackson managed to defeat a superior force by splitting his force, and took some 20,000 soldiers out from McDowell’s force. After this magnificent performance, Jackson and his men wearily crossed the Patapsco further west and returned to their comrades.

While Jackson was maneuvering behind him, McDowell and his 60,000 men battled Beauregard’s 40,000. Towards the end of the day, the Federals imposed themselves and forced Beauregard back in chaotic retreat behind the Little Patuxent. McDowell’s tired men were barely able to continue, and Jackson’s stunt had reduced them to 40,000, equal to Beauregard’s force. But they pressed on, and on the third day they again came to blows. By then, frantic telegrams from Halleck and Lincoln forced McClellan to finally go forward. Magruder’s theatrics, which included several Quaker cannons, were discovered. Rather than try to resist on the unsuitable terrain of the little peninsula, Magruder retreated and joined Beauregard. For his part, McClellan decided not to pursue the Confederates, but instead went North to join McDowell, much to his superiors’ displeasure.

The Second Maryland Campaign

After two days of brutal and bloody fighting, the Confederate and Union forces were finally consolidated in a single place, the Little Patuxent separating them. From his initial 70,000 men, Beauregard was down to 55,000; McDowell had gone from 100,000 to 60,000, having lost 20,000 men in battle and also counting the 20,000 Jackson had managed to mislead and mystify. The result was deadly frustrating to Lincoln, and also to the people, who anxiously waited for results. But now it seemed like victory was within their grasp. With the addition of McClellan’s fresh troops, the Yankees seemed to be in better shape as well. Even though McDowell complained of his subordinate’s timidity, and was miffed when newspapers praised him for escaping the “corking” without really fighting, the Union commander was ready to put that aside and work together for to give the final coup to the rebellion.

But the rebels once again got the drop on the Federals. As soon as dawn broke, they went forward with a chilling rebel yell that took the Yankees by surprise. Tired Union soldiers scattered, until McDowell himself came forward and tried to rally them back. In that moment, a stray shot hit him in the leg. The general was rushed to the medical station and had his leg amputated, but he would not survive the operation, dying the next day. The Confederate side was also struck by disgrace, Beauregard being also hit. Unlike McDowell, he survived, but his wounds still left the Confederates without a commander.

With McDowell unable to command, McClellan took the reigns of the operation. The rebels had decided to retreat all the way to Washington. Seeing the sorry state of the men, and still believing that the many outnumbered him, McClellan decided to not pursue. The Second Maryland Campaign, which included the Battles of Sweetser’s Bridge, Ellicott’s Mills, Catonsville, Franklin, and Little Patuxent, had come to an end.

The results of those three bloody days were 17,000 casualties on the Confederate side, which included almost 3,000 deaths, and 25,000 casualties on the Union side, including 4,000 deaths. The victory wasn’t as great as expected – Washington remained on the hands of the enemy, after all. But, despite the high prize, the rebellion had been dealt a hard blow. It seemed now that just one effort more was needed to destroy what remained of Beauregard’s force, retake Washington, and then march on to Richmond.

Time would prove that these expectations were too sanguine. The greatest and most direct effect of the Second Maryland Campaign was how it changed the goals and methods of both sides. Now firmly convinced that this was going to be a hard and long war, both the Confederate and Union government took new measures that some months ago would seem unthinkable. Breckinridge would increase the power of his government to pursue the war effectively, and he called Longstreet and Lee to Richmond, to replace the ineffective Johnston and the wounded Beauregard, respectively. For his part, Lincoln became more willing to adopt radical measures to end the war, and his thoughts turned towards an Emancipation Proclamation as the best way to do so. The Second Maryland Campaign had not been the decisive battle; rather, it set the stage for the Battle of Washington, which would indeed have much greater effects upon the war and the country.