You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Darkness before Dawn - Purple Phoenix 1416

- Thread starter elerosse

- Start date

CHAPTER 14 – A FINE CATCH AT ACROCORINTH

CHAPTER 14 – A FINE CATCH AT ACROCORINTH

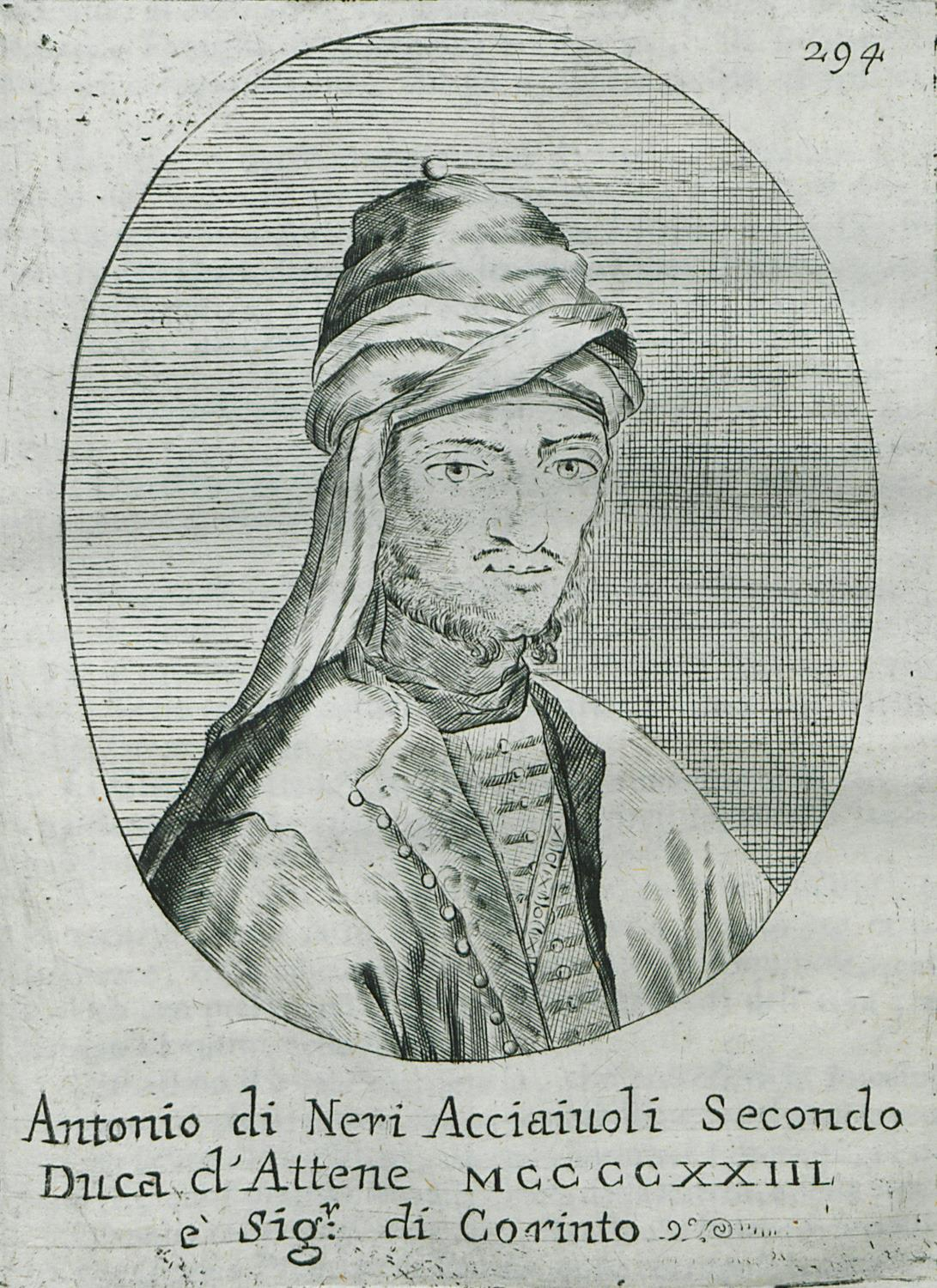

Antonio was the illegitimate son of Nerio I Acciaioli. Nerio conquered of the Duchy of Athens in practice 1388, and formally acknowledged by King Ladislaus of Naples who granted the Duchy of Athens to Nerio and his legitimate male heirs on 11 January 1394.

Nerio I Acciaioli made his last will on 17 September 1394. He bequeathed two important castles in Boeotia, Livadeia and Thebes, to Antonio, but willed most of his domains to his daughter Francesca and left the town of Athens to the Church of Saint Mary on the Acropolis of Athens. When he died on 25 September, his daughters and son soon fought for control over Athens.

During the turmoil, a small Ottoman Turk force attacked the Acropolis of Athens and Nerio's brother, Donato, who had inherited the title of Duke of Athens, was in no position to defend the town. The locals sought assistance from the Venetians in Negroponte, and the Senate of Venice approved the annexation of Athens on 18 March 1395. Antonio sided with the Ottomans during the ensuring skirmishes between the them and the Venetians.

In Antonio led his forces and penetrated deep into Athens, forcing the defenders of the Acropolis to surrender in February 1403 and taking the city. On 1405, a compromise was then reached at the mediation of King Ladislaus of Naples with Venice. Antonio agreed to compensate Venice for the munitions seized in the Acropolis and to send a silk robe to St Mark's Basilica every Christmas. He also pledged to return the goods of the last Venetian governor of Athens, Nicholas Vitturi, to his heirs. In return, Venice recognized Antonio's right to rule Athens and removed a price from his head. As the new duke, Antonio made no effort to honor his part of the deal, and when Venice and Ottomans went to war in 1416, Antonio happily joined his suzerain and raided the Venetian coastal holdings.

****************************************

Using the same marching route as the Achaea campaign year before, the Army of Thessaloniki forced marched for three days to reach Neopatras, the southernmost territory of Roman Thessaly, then boarded upon ships sailing towards Peloponnese.

The situation in Morea seemed desperate to Romans, and Antonio was on major advance across the front.

Antonio had been engaged in constant raiding for the past decade, mostly against the Venetians, but sometimes also intrude Roman lands. His men were well-customed to the hit and run tactics and pillaging methods. So, when Sultan Mehmed sent his envoy to demand a large raid into Roman territory in Peloponnese, Antonio did not hesitate to assemble his men and answer his Sultan. To further increase his strength, Sultan Mehmed provided Antonio with two ‘orta’s to assist his raid in Peloponnese. An orta is a regiment of around 1000 Ottoman soldiers, led by a Chorbaji.

The decision of Sultan Mehmed to encourage and support Antonio to attack the Romans was in part a result of the unexpected Roman result in Achaea, and in part the consequence of Andronikos’ visit to Konstanz and getting tangled in a whispered preparation of a Crusade. Mehmed aimed for Antonio to disrupt the Roman economy by raiding fields and markets, distracting Roman attention towards reconstruction, and sending a warning to the Romans against hostile actions against the Ottomans.

However, what Mehmed wished wasn’t necessarily what Antonio wants. For Antonio, he saw the aid of the Ottomans as an opportune chance to expand his holding into Morea, which he saw was rightfully his. Antonio had his eyes set on the strategically and commercially important city of Corinth, which he had held for extensive period before losing it to the Romans a decade ago.

Antonio crossed the lightly defended Hexamillion Wall on 12 April 1418, and on the same day conquered Corinth by a surprise assault, completing his initial goal. While the Ottoman contingents plundered and pillaged across the undefended Morea lands, Antonio utilized the situation where the Ottomans raiding party would distract many Roman defenders to expand his area of control, gather valuable loot in the rich cities and towns, and prop up his defense against a potential Roman counterattack. To this end, Antonio set his eyes on the next target of his, the city of Polyphengos, which situated along the mountain pass that would open the rest of Morea to Antonio.

Relying on his swiftness and assuming that the fall of Corinth hadn't yet roused the city's defenders, Antonio hastened towards the city gate with his fleetest knights. However, fate was not kind to him, as he arrived just a hair's breadth too late. The defenders had received the news an hour prior from fugitives fleeing Corinth and had successfully shut the gate in time.

Forced to bide his time while his infantry met up and prepared the siege, Antonio sent his knights rampaging through nearby markets and villages, plundering treasures and seizing provisions.

Unfortunately, as Antonio reunited with his infantry and just about to set up camp, and commence preparations for the siege, he received startling news - the Despot of Thessaloniki, Andronikos Palaiologos, had marshaled a force worth attention of 2000 men from Thessaloniki to bolster Morea's defenses.

Antonio had always anticipated Roman reinforcements, but he never anticipated their ability to assemble an army so swiftly. Typically, it took at least a month for a medieval levy-based army to assemble, so he had assumed he would enjoy a six-week window of operational freedom, during which he could loot and besiege without much interference, before the combined forces of Morea and Thessaloniki could mobilize against him. By then, he intended to withdraw his men, treasure, and provisions to Corinth and its surrounding castles, preparing for a protracted defensive siege that would eventually wear down the Romans and force them to concede - or so he had thought.

However, Andronikos's rapid mobilization and advance threw Antonio's plans into disarray, forcing him to make hasty adjustments. As Andronikos was likely to take the route through Thessaly and cross the Corinthian Strait into Peloponnese, Antonio realized the precarious position he would be in if he didn't retreat from his current location. Remaining there would mean being trapped between the Romans landing near Corinth and the Roman forces converging in Mystras. Furthermore, Antonio was uncertain about the defense of Corinth in his absence, and so, reluctantly, he sounded the retreat.

What Antonio was unaware of was the swiftness of Andronikos' movements, exceeding all his expectations. If he had known that the message he received was already three days old, and that by the time he was reading the letter, the young Despot had already landed near Corinth, he would not have hesitated to depart, instead of wasting time gathering his plunder onto ox carts for transportation back to Corinth. This delay cost him a whole day, a precious loss of time.

The battlefield situation was evolving rapidly. Upon receiving information from locals that Antonio had abandoned Corinth and led his main force towards Polyphengos, Andronikos recognized a rare opportunity presented by the gods.

Instead of attempting to besiege Corinth and assault its Latin defenders without their Duke, Andronikos made a strategic decision. He ordered his entire army to embark on a forced march along the western road, the same route Antonio had taken in his advance.

- Acrocorinth (Greek: Ακροκόρινθος, lit. 'Upper Corinth' or 'the acropolis of ancient Corinth') is a monolithic rock overlooking the ancient city of Corinth, Greece. Acrocorinth's fortress was repeatedly used as a last line of defense in southern Greece because it commanded the Isthmus of Corinth, repelling foes from entry by land into the Peloponnese peninsula. Situated along a hilltop and with its secure water supply, Acrocorinth commands the main route into and out of Peloponnese.

The archaic acropolis was already an easily defensible position due to its geomorphology; it was further heavily fortified during the Byzantine Empire as it became the seat of the strategos of the thema of Hellas.

********************************************

By the evening of the same day as their arrival, Andronikos and his elite squadron of 100 horsemen arrived at the formidable fortress of Acrocorinth, guarded only by a scant hundred Latin foot soldiers. His swiftness exceeded all expectations, and the defenders of Acrocorinth, unaware of the Romans' advance, were misled by the setting sun and the dimming sky. They mistakenly identified Andronikos and his knights as friendly forces approaching from Athens.

Spotting the gate ajar, Andronikos wasted no time. He spurred his horse onto the drawbridge, sword drawn, and before anyone in the fortress could react, he swiftly dispatched the unsuspecting guards in his path and galloped into the courtyard.

"I am Andronikos Palaiologos, Despot of Thessaloniki! Your Duke Antonio has been slain by my army of 10,000 men! Surrender now and live, or draw your sword and die!" Andronikos bellowed furiously, circling the courtyard as he repeated his demand. His horsemen poured into the courtyard, joining in the chorus.

The Latin defenders, bewildered by the sudden turn of events, scrambled out of their quarters, some unarmed, most without armor. They looked on in desperation as fully armored warriors dismounted and charged towards them, swords glinting in the fading light.

A few Latin men fell victim to the sword before they could react, and the rest, unprepared and fearing for their lives, panicked. Some fled and barricaded themselves inside their rooms, while most fell to their knees and surrendered. Andronikos ordered the surrendered men to be bound, then commanded his men, who now filled the fortress, to slay any who still resisted. By the end of the night, the ancient fortress of Acrocorinth was firmly in Roman hands, effectively cutting off Antonio from his base in Corinth.

Andronikos took command of the fortress and ordered the interrogation of the Latin captives for information on Antonio's forces. Meanwhile, he awaited the arrival of his main army.

By the early hours of the following day, the main Roman army arrived, promptly setting to work on fortifying the defenses of Acrocorinth. Supplies were secured from neighboring villages, trenches were dug along the primary route Antonio was expected to take, and barriers were erected on nearby hilltops, establishing archery positions that commanded the entire passageway.

Two days later, Antonio and his army emerged, wagons laden with plunder. To his horror, he beheld the Roman flag fluttering proudly atop Acrocorinth. It became apparent to him that his men were now isolated from their supplies and reinforcements.

To secure a safe return, Antonio had to vanquish the defending Romans. With no sustainable source of provisions, they had little time to hesitate before their food and water ran out.

Antonio ordered his army to encamp, dispatching his cavalry to scout the defenders and summoning the marauding Ottoman horsemen to his aid.

The following morning, on the 6th of May 1418, Antonio received intelligence from his scouts that the Roman army numbered only a thousand men or slightly more and had captured the fortress just two days prior. Intent on striking the numerically inferior enemy before they could establish a solid defense, Antonio commanded his 4,000 men to march out and array themselves for battle.

To his surprise, the Roman army did not cower within the camp but instead emerged to form ranks atop a hill. Though numerically inferior, their army was well-ordered, their weapons and armor glinting in the morning sun.

Despite the Romans' evident discipline, Antonio remained confident in his superior numbers and the loyalty and reliability of his men, who had followed him faithfully through years of warfare.

The archers and crossbowmen of both armies unleashed a hail of arrows and bolts upon each other's positions. The Romans, with their advantageous high ground, quickly gained the upper hand, their shots raining down with deadly accuracy on the Latin archers. The casualties among the Latins began to mount alarmingly.

Observing this, Antonio ordered his infantry to advance. They moved forward slowly, many tripping over the palisades and falling victim to the relentless Roman arrows. As they hacked and slashed their way through the palisades, they were met by the Roman infantry, who used their long spears to hold off the numerically superior enemy.

The clash of spears and swords echoed through the hills as the two forces engaged in fierce hand-to-hand combat. Blood splattered the ground as soldiers grunted and gasped for breath amidst the fury of battle. The Latins fought valiantly, but the advantage of high ground, Romans' disciplined formation and effective use of spears gave them the edge.

As the battle ground to a halt, Antonio's frustration grew. He hesitated, torn between sending in his cavalry for a final assault or holding them back as a reserve. His eyes darted nervously between the front line and his knights, waiting tensely for a breakthrough.

Finally, Antonio saw his men slowly being pushed down the hills by the smaller but more effective Roman force. Unable to bear the thought of defeat, as a last-ditch effort, he ordered his knights to charge. With a resounding cheer, they spurred their horses forward, lances lowered and eyes fixed on their enemy.

The Latin knights proved their worth and their frightening reputation in the charge. Despite the uphill climb slowing their momentum, they regained it with each thrust of their lances, pushing the Roman line back step by step. The weight of the Latin cavalry began to tell, their numbers twice those of the Romans, and with each powerful charge, the Roman line began to crumble.

But just then, the gates of Acrocorinth swung open, and out poured a contingent of Roman horsemen, fully armored and led by Andronikos. They sprinted down the hill with terrifying speed, breaking into the ranks of the enemy like a hot knife through butter.

Antonio watched helplessly as his forces began to falter under the renewed Roman assault. The Latins' ranks slowly dissolved like snowflakes in the hot summer sun. The battle was lost, and Antonio could only gather the few remaining men with horses and flee before the victorious Romans. They abandoned all their loot and baggage, fleeing to the coast where they found a fishing boat to carry them back to Athens.

The rest of the Latin infantry on the battlefield were left to their fates. Most surrendered, while a few managed to escape. The battle of Acrocorinth lasted for half a day, resulting in over a thousand Latin casualties and more than a thousand captured, against a few hundred Roman losses. Of the four thousand Latins who had departed from Athens, only a few hundred returned safely.

With the destruction of Athens' main force, the remaining defenders of Corinth knew they could not withstand a Roman siege without reinforcements. They had no choice but to abandon the city and withdraw into their own territory.

Upon hearing the news, the rampaging Ottoman Turks immediately abandoned their pillaging campaign. Fearful of being surrounded in hostile territory by a newly victorious army, and with the Morean army on the move, they fled north, abandoning most of their loot before returning to Ottoman Thessaly.

Thus, the Athenian campaign in Morea lasted only a month before collapsing into a crushing defeat. With most of its army gone and its garrison stripped bare, Athens' defense was helplessly exposed to a strong Roman retaliation.

Antonio was the illegitimate son of Nerio I Acciaioli. Nerio conquered of the Duchy of Athens in practice 1388, and formally acknowledged by King Ladislaus of Naples who granted the Duchy of Athens to Nerio and his legitimate male heirs on 11 January 1394.

Nerio I Acciaioli made his last will on 17 September 1394. He bequeathed two important castles in Boeotia, Livadeia and Thebes, to Antonio, but willed most of his domains to his daughter Francesca and left the town of Athens to the Church of Saint Mary on the Acropolis of Athens. When he died on 25 September, his daughters and son soon fought for control over Athens.

During the turmoil, a small Ottoman Turk force attacked the Acropolis of Athens and Nerio's brother, Donato, who had inherited the title of Duke of Athens, was in no position to defend the town. The locals sought assistance from the Venetians in Negroponte, and the Senate of Venice approved the annexation of Athens on 18 March 1395. Antonio sided with the Ottomans during the ensuring skirmishes between the them and the Venetians.

In Antonio led his forces and penetrated deep into Athens, forcing the defenders of the Acropolis to surrender in February 1403 and taking the city. On 1405, a compromise was then reached at the mediation of King Ladislaus of Naples with Venice. Antonio agreed to compensate Venice for the munitions seized in the Acropolis and to send a silk robe to St Mark's Basilica every Christmas. He also pledged to return the goods of the last Venetian governor of Athens, Nicholas Vitturi, to his heirs. In return, Venice recognized Antonio's right to rule Athens and removed a price from his head. As the new duke, Antonio made no effort to honor his part of the deal, and when Venice and Ottomans went to war in 1416, Antonio happily joined his suzerain and raided the Venetian coastal holdings.

****************************************

Using the same marching route as the Achaea campaign year before, the Army of Thessaloniki forced marched for three days to reach Neopatras, the southernmost territory of Roman Thessaly, then boarded upon ships sailing towards Peloponnese.

The situation in Morea seemed desperate to Romans, and Antonio was on major advance across the front.

Antonio had been engaged in constant raiding for the past decade, mostly against the Venetians, but sometimes also intrude Roman lands. His men were well-customed to the hit and run tactics and pillaging methods. So, when Sultan Mehmed sent his envoy to demand a large raid into Roman territory in Peloponnese, Antonio did not hesitate to assemble his men and answer his Sultan. To further increase his strength, Sultan Mehmed provided Antonio with two ‘orta’s to assist his raid in Peloponnese. An orta is a regiment of around 1000 Ottoman soldiers, led by a Chorbaji.

The decision of Sultan Mehmed to encourage and support Antonio to attack the Romans was in part a result of the unexpected Roman result in Achaea, and in part the consequence of Andronikos’ visit to Konstanz and getting tangled in a whispered preparation of a Crusade. Mehmed aimed for Antonio to disrupt the Roman economy by raiding fields and markets, distracting Roman attention towards reconstruction, and sending a warning to the Romans against hostile actions against the Ottomans.

However, what Mehmed wished wasn’t necessarily what Antonio wants. For Antonio, he saw the aid of the Ottomans as an opportune chance to expand his holding into Morea, which he saw was rightfully his. Antonio had his eyes set on the strategically and commercially important city of Corinth, which he had held for extensive period before losing it to the Romans a decade ago.

Antonio crossed the lightly defended Hexamillion Wall on 12 April 1418, and on the same day conquered Corinth by a surprise assault, completing his initial goal. While the Ottoman contingents plundered and pillaged across the undefended Morea lands, Antonio utilized the situation where the Ottomans raiding party would distract many Roman defenders to expand his area of control, gather valuable loot in the rich cities and towns, and prop up his defense against a potential Roman counterattack. To this end, Antonio set his eyes on the next target of his, the city of Polyphengos, which situated along the mountain pass that would open the rest of Morea to Antonio.

Relying on his swiftness and assuming that the fall of Corinth hadn't yet roused the city's defenders, Antonio hastened towards the city gate with his fleetest knights. However, fate was not kind to him, as he arrived just a hair's breadth too late. The defenders had received the news an hour prior from fugitives fleeing Corinth and had successfully shut the gate in time.

Forced to bide his time while his infantry met up and prepared the siege, Antonio sent his knights rampaging through nearby markets and villages, plundering treasures and seizing provisions.

Unfortunately, as Antonio reunited with his infantry and just about to set up camp, and commence preparations for the siege, he received startling news - the Despot of Thessaloniki, Andronikos Palaiologos, had marshaled a force worth attention of 2000 men from Thessaloniki to bolster Morea's defenses.

Antonio had always anticipated Roman reinforcements, but he never anticipated their ability to assemble an army so swiftly. Typically, it took at least a month for a medieval levy-based army to assemble, so he had assumed he would enjoy a six-week window of operational freedom, during which he could loot and besiege without much interference, before the combined forces of Morea and Thessaloniki could mobilize against him. By then, he intended to withdraw his men, treasure, and provisions to Corinth and its surrounding castles, preparing for a protracted defensive siege that would eventually wear down the Romans and force them to concede - or so he had thought.

However, Andronikos's rapid mobilization and advance threw Antonio's plans into disarray, forcing him to make hasty adjustments. As Andronikos was likely to take the route through Thessaly and cross the Corinthian Strait into Peloponnese, Antonio realized the precarious position he would be in if he didn't retreat from his current location. Remaining there would mean being trapped between the Romans landing near Corinth and the Roman forces converging in Mystras. Furthermore, Antonio was uncertain about the defense of Corinth in his absence, and so, reluctantly, he sounded the retreat.

What Antonio was unaware of was the swiftness of Andronikos' movements, exceeding all his expectations. If he had known that the message he received was already three days old, and that by the time he was reading the letter, the young Despot had already landed near Corinth, he would not have hesitated to depart, instead of wasting time gathering his plunder onto ox carts for transportation back to Corinth. This delay cost him a whole day, a precious loss of time.

The battlefield situation was evolving rapidly. Upon receiving information from locals that Antonio had abandoned Corinth and led his main force towards Polyphengos, Andronikos recognized a rare opportunity presented by the gods.

Instead of attempting to besiege Corinth and assault its Latin defenders without their Duke, Andronikos made a strategic decision. He ordered his entire army to embark on a forced march along the western road, the same route Antonio had taken in his advance.

- Acrocorinth (Greek: Ακροκόρινθος, lit. 'Upper Corinth' or 'the acropolis of ancient Corinth') is a monolithic rock overlooking the ancient city of Corinth, Greece. Acrocorinth's fortress was repeatedly used as a last line of defense in southern Greece because it commanded the Isthmus of Corinth, repelling foes from entry by land into the Peloponnese peninsula. Situated along a hilltop and with its secure water supply, Acrocorinth commands the main route into and out of Peloponnese.

The archaic acropolis was already an easily defensible position due to its geomorphology; it was further heavily fortified during the Byzantine Empire as it became the seat of the strategos of the thema of Hellas.

********************************************

By the evening of the same day as their arrival, Andronikos and his elite squadron of 100 horsemen arrived at the formidable fortress of Acrocorinth, guarded only by a scant hundred Latin foot soldiers. His swiftness exceeded all expectations, and the defenders of Acrocorinth, unaware of the Romans' advance, were misled by the setting sun and the dimming sky. They mistakenly identified Andronikos and his knights as friendly forces approaching from Athens.

Spotting the gate ajar, Andronikos wasted no time. He spurred his horse onto the drawbridge, sword drawn, and before anyone in the fortress could react, he swiftly dispatched the unsuspecting guards in his path and galloped into the courtyard.

"I am Andronikos Palaiologos, Despot of Thessaloniki! Your Duke Antonio has been slain by my army of 10,000 men! Surrender now and live, or draw your sword and die!" Andronikos bellowed furiously, circling the courtyard as he repeated his demand. His horsemen poured into the courtyard, joining in the chorus.

The Latin defenders, bewildered by the sudden turn of events, scrambled out of their quarters, some unarmed, most without armor. They looked on in desperation as fully armored warriors dismounted and charged towards them, swords glinting in the fading light.

A few Latin men fell victim to the sword before they could react, and the rest, unprepared and fearing for their lives, panicked. Some fled and barricaded themselves inside their rooms, while most fell to their knees and surrendered. Andronikos ordered the surrendered men to be bound, then commanded his men, who now filled the fortress, to slay any who still resisted. By the end of the night, the ancient fortress of Acrocorinth was firmly in Roman hands, effectively cutting off Antonio from his base in Corinth.

Andronikos took command of the fortress and ordered the interrogation of the Latin captives for information on Antonio's forces. Meanwhile, he awaited the arrival of his main army.

By the early hours of the following day, the main Roman army arrived, promptly setting to work on fortifying the defenses of Acrocorinth. Supplies were secured from neighboring villages, trenches were dug along the primary route Antonio was expected to take, and barriers were erected on nearby hilltops, establishing archery positions that commanded the entire passageway.

Two days later, Antonio and his army emerged, wagons laden with plunder. To his horror, he beheld the Roman flag fluttering proudly atop Acrocorinth. It became apparent to him that his men were now isolated from their supplies and reinforcements.

To secure a safe return, Antonio had to vanquish the defending Romans. With no sustainable source of provisions, they had little time to hesitate before their food and water ran out.

Antonio ordered his army to encamp, dispatching his cavalry to scout the defenders and summoning the marauding Ottoman horsemen to his aid.

The following morning, on the 6th of May 1418, Antonio received intelligence from his scouts that the Roman army numbered only a thousand men or slightly more and had captured the fortress just two days prior. Intent on striking the numerically inferior enemy before they could establish a solid defense, Antonio commanded his 4,000 men to march out and array themselves for battle.

To his surprise, the Roman army did not cower within the camp but instead emerged to form ranks atop a hill. Though numerically inferior, their army was well-ordered, their weapons and armor glinting in the morning sun.

Despite the Romans' evident discipline, Antonio remained confident in his superior numbers and the loyalty and reliability of his men, who had followed him faithfully through years of warfare.

The archers and crossbowmen of both armies unleashed a hail of arrows and bolts upon each other's positions. The Romans, with their advantageous high ground, quickly gained the upper hand, their shots raining down with deadly accuracy on the Latin archers. The casualties among the Latins began to mount alarmingly.

Observing this, Antonio ordered his infantry to advance. They moved forward slowly, many tripping over the palisades and falling victim to the relentless Roman arrows. As they hacked and slashed their way through the palisades, they were met by the Roman infantry, who used their long spears to hold off the numerically superior enemy.

The clash of spears and swords echoed through the hills as the two forces engaged in fierce hand-to-hand combat. Blood splattered the ground as soldiers grunted and gasped for breath amidst the fury of battle. The Latins fought valiantly, but the advantage of high ground, Romans' disciplined formation and effective use of spears gave them the edge.

As the battle ground to a halt, Antonio's frustration grew. He hesitated, torn between sending in his cavalry for a final assault or holding them back as a reserve. His eyes darted nervously between the front line and his knights, waiting tensely for a breakthrough.

Finally, Antonio saw his men slowly being pushed down the hills by the smaller but more effective Roman force. Unable to bear the thought of defeat, as a last-ditch effort, he ordered his knights to charge. With a resounding cheer, they spurred their horses forward, lances lowered and eyes fixed on their enemy.

The Latin knights proved their worth and their frightening reputation in the charge. Despite the uphill climb slowing their momentum, they regained it with each thrust of their lances, pushing the Roman line back step by step. The weight of the Latin cavalry began to tell, their numbers twice those of the Romans, and with each powerful charge, the Roman line began to crumble.

But just then, the gates of Acrocorinth swung open, and out poured a contingent of Roman horsemen, fully armored and led by Andronikos. They sprinted down the hill with terrifying speed, breaking into the ranks of the enemy like a hot knife through butter.

Antonio watched helplessly as his forces began to falter under the renewed Roman assault. The Latins' ranks slowly dissolved like snowflakes in the hot summer sun. The battle was lost, and Antonio could only gather the few remaining men with horses and flee before the victorious Romans. They abandoned all their loot and baggage, fleeing to the coast where they found a fishing boat to carry them back to Athens.

The rest of the Latin infantry on the battlefield were left to their fates. Most surrendered, while a few managed to escape. The battle of Acrocorinth lasted for half a day, resulting in over a thousand Latin casualties and more than a thousand captured, against a few hundred Roman losses. Of the four thousand Latins who had departed from Athens, only a few hundred returned safely.

With the destruction of Athens' main force, the remaining defenders of Corinth knew they could not withstand a Roman siege without reinforcements. They had no choice but to abandon the city and withdraw into their own territory.

Upon hearing the news, the rampaging Ottoman Turks immediately abandoned their pillaging campaign. Fearful of being surrounded in hostile territory by a newly victorious army, and with the Morean army on the move, they fled north, abandoning most of their loot before returning to Ottoman Thessaly.

Thus, the Athenian campaign in Morea lasted only a month before collapsing into a crushing defeat. With most of its army gone and its garrison stripped bare, Athens' defense was helplessly exposed to a strong Roman retaliation.

Last edited:

Andronikos recognized a rare opportunity presented by the gods.

Will do once I get access to a laptop

@elerosse

While I was reading about the Catalan company, I came across these curious details, namely the recruitment of Latinikon units by the Basileus of Rhomanois , in particular it seems that Charles VI sent about 1200 men commanded by Marshal Boucicaut to Manouel Paleologus, while in 1445 the Duke of Burgundy sends 300 knights to the Despot of Morea ( future Constantine XI ) now Andronikos has traveled around Latin Europe, so how absurd would it be to think that he has created a network of contacts from which he can try to ask for the recruitment of small groups of knights/men-at-arms ?, perhaps Sigismund, to partially remedy his inability to carry out a crusade in the short term, decides to donate small military units from his disparate possessions as an excuse to Constantinople, as well as a way to make it clear that he still intends to keep his word in the future

While I was reading about the Catalan company, I came across these curious details, namely the recruitment of Latinikon units by the Basileus of Rhomanois , in particular it seems that Charles VI sent about 1200 men commanded by Marshal Boucicaut to Manouel Paleologus, while in 1445 the Duke of Burgundy sends 300 knights to the Despot of Morea ( future Constantine XI ) now Andronikos has traveled around Latin Europe, so how absurd would it be to think that he has created a network of contacts from which he can try to ask for the recruitment of small groups of knights/men-at-arms ?, perhaps Sigismund, to partially remedy his inability to carry out a crusade in the short term, decides to donate small military units from his disparate possessions as an excuse to Constantinople, as well as a way to make it clear that he still intends to keep his word in the future

Last edited:

Yes I am aware of the small Latin contingents that serve the Romans in one way or another. If I recalled correctly, the knights Manuel II employed helped him fend against the Ottomans in Gallipoli in the aftermath of Nicopolis Crusade.@elerosse

While I was reading about the Catalan company, I came across these curious details, namely the recruitment of Latinikon units by the Basileus of Rhomanois , in particular it seems that Charles VI sent about 1200 men commanded by Marshal Boucicaut to Manouel Paleologus, while in 1445 the Duke of Burgundy sends 300 knights to the Despot of Morea ( future Constantine XI ) now Andronikos has traveled around Latin Europe, so how absurd would it be to think that he has created a network of contacts from which he can try to ask for the recruitment of small groups of knights/men-at-arms ?, perhaps Sigismund, to partially remedy his inability to carry out a crusade in the short term, decides to donate small military units from his disparate possessions as an excuse to Constantinople, as well as a way to make it clear that he still intends to keep his word in the future

As to the possibility of Andronikos employing Latin men at arms, I definitely see it as plausible, however they would have more impact in the initial phases, whereas when we reach the decisive battle against the mighty grand army with combined arms tactics such as the Ottomans, they will only be a part of the comprehensive strength of Roman army

Great chapter, the Latins were defeated and the Ottomans soldiers fled, most likely causing more trouble for Mehmed and Bedreddin gaining more sympathy. Can't wait to see the reaction in Constantinople, how Manuel II deals with such a great victory will be nice to see. He'll probably milk the political/military success for all it's worth when dealing with Mehmed. Will this be threadmarked?

Last edited:

I was in a hurry and forgot to add them, they’ve been added now

Great chapter, the Latins were defeated and the Ottomans soldiers fled, most likely causing more trouble for Mehmed and Bedreddin gaining more sympathy. Can't wait to see the reaction in Constantinople, how Manuell deals with such a great victory will be nice to see. He'll probably milk the political/military success for all it's worth when dealing with Mehmed. Will this be threadmarked?

Pretty sure the Church of a monotheistic religion such as Christianity, who's referred as a jealous God, wouldn't refer to multiple Gods.But that’s also what the Church says

Yeah, to clarify, what I meant was the Church also saw Andronikos as heretic, ergo the words “that’s heresy” would surely be muttered by the Church. CheersPretty sure the Church of a monotheistic religion such as Christianity, who's referred as a jealous God, wouldn't refer to multiple Gods.

Well as a follower of Plethon it might well be what he believes himself though still apt to be misunderstood or used against him by the self interested Sorry I meant the ah devout and noble church fathersPretty sure the Church of a monotheistic religion such as Christianity, who's referred as a jealous God, wouldn't refer to multiple Gods.

An inquiry for help - I am about to reach a phase where the TL would be better illustrated with an updated map that showed the progress compared to the historical ones. As I am no genius with map modelling, I wonder if someone could advice me some good tools/website that could turn a historical map and adjust the borders without looking cringe?

I'd use Mapchart: https://www.mapchart.net/An inquiry for help - I am about to reach a phase where the TL would be better illustrated with an updated map that showed the progress compared to the historical ones. As I am no genius with map modelling, I wonder if someone could advice me some good tools/website that could turn a historical map and adjust the borders without looking cringe?

Also use historical maps as a basis for your maps.

Thanks for the recommendation, seems like the closest I could get was a EU4 like map, haven't seen the option to use other map templates, maybe it needs paid membership?

Don't know about any paid membership. When using Mapchart, stick to using the World Map: Advanced and just zoom in on Eastern Europe and Turkey region. Hope this helps 👍👍👍Thanks for the recommendation, seems like the closest I could get was a EU4 like map, haven't seen the option to use other map templates, maybe it needs paid membership?

Seems like that's the template to go, I'll mingle with it tomorrow, thanks!Don't know about any paid membership. When using Mapchart, stick to using the World Map: Advanced and just zoom in on Eastern Europe and Turkey region. Hope this helps 👍👍👍

Share: