Part 1

Skaqua, Russian America

June 1905

The man on the gangway of the Katyusha had a newspaper, and it was bordered in black.

Lev Khodulevich saw it even before the portmaster did. In theory, he was at the harbor to take note of incoming foreigners, which was one of his duties as deputy chief of police. It wasn’t a duty he took very seriously – who but foreigners came to Skaqua these days? – but he was a conscientious man, so even on a rainy morning like this one, he always went to meet the ships. And so he was the first to see the broadsheet that brought news of the disaster at Tsushima.

He didn’t, of course, know yet that these were the tidings the newspaper brought, and he almost didn’t learn. The man with the paper under his arm – a black-suited gentleman of forty with a neatly trimmed beard and a bureaucrat’s air of self-importance – was almost to the pier now, and when Khodulevich took him by the arm, he twisted angrily and pulled away. “Let go of me, zhid,” he said, and looked ready to spit.

Khodulevich paid the insult no mind – this wasn’t the first time he’d heard it, or even the thousandth. He kept a firm grip on the man’s arm, stood in his way, and waited for him to see. And after a tense moment, the official registered the hard veteran’s face and police uniform in front of him, and realized that zhid or not, this was someone he had best not cross.

“The newspaper,” Khodulevich said. “Let me see.” And he did. It was the Vladivostok paper from two weeks before, and it told of how Admiral Togo had sent the flower of the Russian navy to the bottom of the sea. Eleven battleships were lost – all the battleships in the fleet – and thirty other vessels sunk or scattered… and yes, when Khodulevich read to the end of the list, the three ships of the Alyeska coastal patrol had gone down with the others. Those ships, and all too likely most of the men on them, would never come home.

“Bozhe moi!” he said, his voice low and almost prayerful. He’d known the war wasn’t going well, but this was worse than anyone could have imagined. He knew some of the sailors on those ships, and now he would have to visit their families and tell them…

“Are you done with me, zhid?” the official asked. The insult hung in the air, and this time Khodulevich wasn’t sure he wanted to ignore it. But just then, a young man with a document in his hand barreled down the gangway and nearly bowled them over, and with both of them having a new target for their anger, the moment was broken. Khodulevich released his grip and the official walked away without further comment, disappearing into the misty streets that led away from the terminal.

A minute later, Khodulevich took another of those streets and went to morning prayers.

There hadn’t been a synagogue in Skaqua when Khodulevich had first come there. Russian America was a very long way from the Pale of Settlement to which Jews were confined, and most of the exceptions – university laureates, merchants of the first rank, those few who had been ennobled – had little interest in visiting frontier outposts. Only those like Khodulevich himself – the cantonists, Jewish boys who had been drafted at twelve and finished their twenty years’ service in the army – would fetch up in a place like this, and when he was mustered out, only two others had lived there. A few more had come year by year, soldiers who settled where they were stationed, but never enough to build a house of prayer.

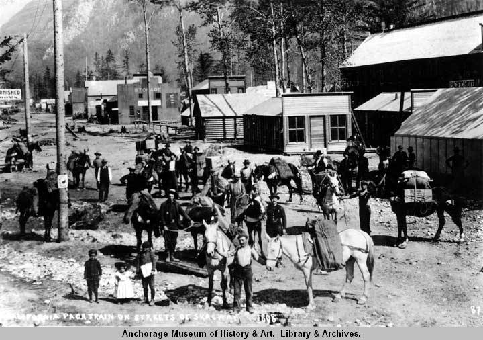

But then had come the gold rush. Americans poured through Skaqua to the Klondike gold fields, and as always, they left a residue behind – merchants and outfitters, saloon-keepers and whores, luckless miners who’d lost their claims and were reduced to seeking work at the port. Now, in the year of grace 1905, there were four Americans in Skaqua for every Russian, and though it was technically against the law, some of them were Jews. And one of them – Sam Katz, who’d struck it rich north of Dawson and struck it even richer as a druggist – had built a synagogue to thank God for his good fortune.

The building was well away from the main streets, on the lower slopes of the mountain where the governor and the garrison commander wouldn’t have to notice it. At this time of day, the path that led to it was shrouded in fog, and when the low wooden house appeared through the fir trees, it came almost as a surprise. But the door stood open and Khodulevich could see that he wasn’t the first one there.

The man sitting in the anteroom wasn’t one of the newcomers – Mendel, a fellow cantonist, had finished his service as an army tailor fifteen years before and set up shop in town. He wasn’t wearing a tallis or tefillin and looked on with amusement as Khodulevich put on his. Mendel was an atheist, a radical, who at other times and in other places liked to fulminate about the opiate of the people. But in the Russian Empire, a Jewish atheist was still a Jew, and here was where the society of other Jews was to be found.

“What news on the Rialto, Lev?” Mendel asked. Khodulevich recognized the reference vaguely – Mendel had taken up reading English since the Americans came, and he had an annoying habit of showing off his erudition.

“We lost the war, nothing else.”

“All at once?”

“Two thirds of our fleet sunk or captured. I don’t see how we can keep fighting now.”

“Baruch Hashem.”

“You’re talking about twelve thousand men,” Khodulevich said, but his voice was mild; it wasn’t as if he had just learned which way Mendel’s opinions ran.

“I’m talking about a revolution! There are strikes and mutinies already, and after this…”

Khodulevich reflected that Mendel was probably right. He’d heard the news of peasant uprisings, soldiers’ strikes, street fights between workers and police; the Tsar, it was said, had agreed to an advisory assembly and labor reforms, but these were concessions that pleased nobody. The government was already holding on by its fingernails, and with the catastrophe at Tsushima…

“Even here now,” Mendel said. And maybe he was right about that too – Alyeska had been peaceful thus far, but there had been rumblings of discontent in Novo-Arkhangelsk and memoranda had come down warning the police to be watchful for sedition. And here the sedition was, and Mendel was speaking it even to someone duty-bound to make a report. The unwritten rule was that words spoken in the synagogue remained there, but that same rule stipulated certain boundaries, and Mendel was close to crossing them if he hadn’t done so already.

“Careful,” Khodulevich said, and put his index finger to his lips. Don’t say anything that I’ll have to notice – I, or the spies we both know are here. It seemed that Mendel was going to answer him, but his words died unspoken as the Americans came in.

They were a motley group of seven, led by the man who called himself their rabbi – Khodulevich had made inquiries, and he was really a confidence man with a police record in Kansas City, but he’d got an education from somewhere, he was skilled at wheedling enough money from Katz to keep the synagogue running, and he played the part well. He did so now, greeting Khodulevich and gesturing with both hands into the sanctuary.

Old Itzik was there already – he must have come even before Mendel – and with Khodulevich and the Americans, they just made a minyan. They settled to their prayers, all except Mendel who looked on in silent amusement and who shook his head in good humor when the rabbi made his ritual offer of an aliyah. The fog was lifting outside, and the view across the valley lent a sense of peace to the service, but when it was over, the rabbi and Katz motioned the other Americans into a whispered conversation, and even Mendel couldn’t tell what they were talking about.

The first of the sailors’ families lived in a shack at the edge of town, at the bottom of the path. The father had already gone to his work as a woodcutter, but the mother was doing the washing in back. She hadn’t heard the news, but something in Khodulevich’s face told her, and even before he started speaking, the tears had started to flow. When he had said the words his duty required, she took him inside and showed him a photograph – a young man of eighteen, proud in his naval uniform. A few letters lay beside it, and now these were all she would have of him. “Think of him sometimes,” she said. “Promise me he will be remembered.”

The second family was two streets away, and they called him a filthy zhid who wasn’t fit to clean their outhouse.

From there, Khodulevich’s route took him into the city. The watch in his pocket told him it was nearing eight o’clock, and the Alexander III Promenade was bustling; the stores were full of customers, carts filled with lumber and mining equipment rumbled down the dirt roadway, and men reeled out of already-open saloons. A few of them saw Khodulevich and straightened up in a hurry; most knew that as long as they stayed peaceable, they weren’t worth his time.

That much was ordinary. But when he passed knots of people talking in the street – some in Russian, most in English – the topic of conversation was always the same. The news of Tsushima spread fast as bad news always did, and by now it had no doubt reached the farthest edges of town; in all likelihood, Khodulevich’s visits to the other sailors’ families would be superfluous.

Not everyone, of course, was taking the news in the same way. The Russians, mostly, were mourning, both for the sailors and their country. Others shut up hastily when Khodulevich approached, which meant that they felt as Mendel did. But the Americans neither mourned nor celebrated in secret; their gestures were emphatic and the rising tone of their voices brimmed over with eagerness.

“The patrol boats are gone,” said a florid-faced outfitter standing outside his warehouse. “There’s nothing between here and the islands – a fleet of fishing boats could get us to Novo-Arkhangelsk.”

The man next to him nodded vigorously. “Take the fort here, get a thousand men across – we could plant the flag within a week.”

“Roosevelt?” asked a third.

“He’ll agree, once it’s done. He’s not the kind to sit and think about it for five years like they did with Hawaii…”

They went on in that vein for some time, taking no notice of Khodulevich – they were either confident they could do nothing to stop him or, more likely, didn’t think he could understand English. But nor did they say enough for Khodulevich to tell if they were serious. None of them struck him as soldiers, and none had anything like a plan; were they really scheming to plant the American flag in the Alyeskan capital, or were they simply hoping for that as they’d no doubt done since they arrived? Would there soon be conversations like this in the Tanana gold fields or the diggings near Fort Nikolaevskaya? Would any of them be more serious than this – were there caches of arms somewhere in town, held against just this kind of happenstance?

Serious or not, these were things the garrison commander should know, and Khodulevich would report to him directly after breakfast.

Breakfast itself was two doors down, at one of the few taverns on the Promenade with signs in both Russian and English. The street was mostly American now but for the public buildings at the far end, but some of the old Russian businesses remained, and one of them was the tavern owned by Khodulevich’s wife. She was behind the bar now, serving coffee and bacon to hungry miners and drinks to thirsty ones, and her broad, dark Tlingit face brightened and grew gentle as she saw him enter.

“Some eggs, Lena?” he said, and she broke three onto the stove as he dragged a stool up to the bar. She didn’t need to ask how he took them, and she knew he wouldn’t want bacon; she also knew how he took his coffee, and that was on the bar even before he sat down.

She, of all people, seemed indifferent to the battle. Like many of her people, she’d been baptized as a child and taught Russian by the missionaries who’d given her a Christian name, but she wasn’t Russian, and she certainly wasn’t American. “The poor young sailors,” she said, but she said that because she was a mother, not because she was a patriot.

“The poor young sailors indeed,” repeated a man at Khodulevich’s right – Katz, he realized. What was Katz doing here? “But at least this will bring the end of the war.”

Khodulevich looked around quickly – Katz had spoken English, but a good half of the Russians in the room would understand, and some would take offense at welcoming the war ending this way. Fortunately, none of them seemed to have heard, but conversations in saloons had a way of becoming louder. “Be careful,” he hissed, much as he had to Mendel two hours before. “Between dreams of revolution and dreams of the Stars and Stripes, it will be easy to get into a fight today and hard to get out of one.”

Katz nodded and rose from his stool, but he wasn’t contrite. “Some fights are worth having,” he said. “Remember that you’re a Jew.”

There was no time to ask Katz what he’d meant before he left, but suddenly Khodulevich knew. In Russia, there were laws restricting where Jews could live and what professions they could follow; there were quotas of boys to be drafted for the army; there were evictions and pogroms. American Jews could live anywhere, work at any job, vote and hold office; many didn’t love them, but they were equal under the law. Katz was trying to recruit him to the American side, which meant that he saw an American coup as something more than a hope – and if someone as rich and well-connected as Katz thought so, then it might well be so.

It was enough to make Khodulevich wonder what his hopes were. He was sixty-three and had fought for Russia for twenty years; his status as a veteran exempted him from most of the restrictive laws, and he’d risen about as far as a retired Jewish cantonist could rise. His life in Alyeska wasn’t a bad one, and he had little love for the rabbis and rich merchants among the Mogilev Jews who’d sent poor boys like him to the army rather than give up their own sons. But he remembered other things he’d seen and stories he’d heard, and just as he’d fought for Russia, he’d fought hard to stay a Jew when the missionaries in the cantonist schools had tried to make a Christian of him. And he'd been cursed as a zhid twice this morning. A country where Jews were free – that called to him in a way that Mendel’s talk of revolution hadn’t.

He had things to think about before he made his report. He needed to talk – to Lena, if no one else. But then there were gunshots and shouting outside. He ran into the street almost gratefully – there were no doubts about what to do now – and at the sight of his uniform, the gathering crowd parted and motioned him to the corpse. .

A corpse, he realized, that he’d seen before. It was the man he’d seen running down the gangway of the Katyusha, and he was dead with three bullets in him.

June 1905

The man on the gangway of the Katyusha had a newspaper, and it was bordered in black.

Lev Khodulevich saw it even before the portmaster did. In theory, he was at the harbor to take note of incoming foreigners, which was one of his duties as deputy chief of police. It wasn’t a duty he took very seriously – who but foreigners came to Skaqua these days? – but he was a conscientious man, so even on a rainy morning like this one, he always went to meet the ships. And so he was the first to see the broadsheet that brought news of the disaster at Tsushima.

He didn’t, of course, know yet that these were the tidings the newspaper brought, and he almost didn’t learn. The man with the paper under his arm – a black-suited gentleman of forty with a neatly trimmed beard and a bureaucrat’s air of self-importance – was almost to the pier now, and when Khodulevich took him by the arm, he twisted angrily and pulled away. “Let go of me, zhid,” he said, and looked ready to spit.

Khodulevich paid the insult no mind – this wasn’t the first time he’d heard it, or even the thousandth. He kept a firm grip on the man’s arm, stood in his way, and waited for him to see. And after a tense moment, the official registered the hard veteran’s face and police uniform in front of him, and realized that zhid or not, this was someone he had best not cross.

“The newspaper,” Khodulevich said. “Let me see.” And he did. It was the Vladivostok paper from two weeks before, and it told of how Admiral Togo had sent the flower of the Russian navy to the bottom of the sea. Eleven battleships were lost – all the battleships in the fleet – and thirty other vessels sunk or scattered… and yes, when Khodulevich read to the end of the list, the three ships of the Alyeska coastal patrol had gone down with the others. Those ships, and all too likely most of the men on them, would never come home.

“Bozhe moi!” he said, his voice low and almost prayerful. He’d known the war wasn’t going well, but this was worse than anyone could have imagined. He knew some of the sailors on those ships, and now he would have to visit their families and tell them…

“Are you done with me, zhid?” the official asked. The insult hung in the air, and this time Khodulevich wasn’t sure he wanted to ignore it. But just then, a young man with a document in his hand barreled down the gangway and nearly bowled them over, and with both of them having a new target for their anger, the moment was broken. Khodulevich released his grip and the official walked away without further comment, disappearing into the misty streets that led away from the terminal.

A minute later, Khodulevich took another of those streets and went to morning prayers.

#

There hadn’t been a synagogue in Skaqua when Khodulevich had first come there. Russian America was a very long way from the Pale of Settlement to which Jews were confined, and most of the exceptions – university laureates, merchants of the first rank, those few who had been ennobled – had little interest in visiting frontier outposts. Only those like Khodulevich himself – the cantonists, Jewish boys who had been drafted at twelve and finished their twenty years’ service in the army – would fetch up in a place like this, and when he was mustered out, only two others had lived there. A few more had come year by year, soldiers who settled where they were stationed, but never enough to build a house of prayer.

But then had come the gold rush. Americans poured through Skaqua to the Klondike gold fields, and as always, they left a residue behind – merchants and outfitters, saloon-keepers and whores, luckless miners who’d lost their claims and were reduced to seeking work at the port. Now, in the year of grace 1905, there were four Americans in Skaqua for every Russian, and though it was technically against the law, some of them were Jews. And one of them – Sam Katz, who’d struck it rich north of Dawson and struck it even richer as a druggist – had built a synagogue to thank God for his good fortune.

The building was well away from the main streets, on the lower slopes of the mountain where the governor and the garrison commander wouldn’t have to notice it. At this time of day, the path that led to it was shrouded in fog, and when the low wooden house appeared through the fir trees, it came almost as a surprise. But the door stood open and Khodulevich could see that he wasn’t the first one there.

The man sitting in the anteroom wasn’t one of the newcomers – Mendel, a fellow cantonist, had finished his service as an army tailor fifteen years before and set up shop in town. He wasn’t wearing a tallis or tefillin and looked on with amusement as Khodulevich put on his. Mendel was an atheist, a radical, who at other times and in other places liked to fulminate about the opiate of the people. But in the Russian Empire, a Jewish atheist was still a Jew, and here was where the society of other Jews was to be found.

“What news on the Rialto, Lev?” Mendel asked. Khodulevich recognized the reference vaguely – Mendel had taken up reading English since the Americans came, and he had an annoying habit of showing off his erudition.

“We lost the war, nothing else.”

“All at once?”

“Two thirds of our fleet sunk or captured. I don’t see how we can keep fighting now.”

“Baruch Hashem.”

“You’re talking about twelve thousand men,” Khodulevich said, but his voice was mild; it wasn’t as if he had just learned which way Mendel’s opinions ran.

“I’m talking about a revolution! There are strikes and mutinies already, and after this…”

Khodulevich reflected that Mendel was probably right. He’d heard the news of peasant uprisings, soldiers’ strikes, street fights between workers and police; the Tsar, it was said, had agreed to an advisory assembly and labor reforms, but these were concessions that pleased nobody. The government was already holding on by its fingernails, and with the catastrophe at Tsushima…

“Even here now,” Mendel said. And maybe he was right about that too – Alyeska had been peaceful thus far, but there had been rumblings of discontent in Novo-Arkhangelsk and memoranda had come down warning the police to be watchful for sedition. And here the sedition was, and Mendel was speaking it even to someone duty-bound to make a report. The unwritten rule was that words spoken in the synagogue remained there, but that same rule stipulated certain boundaries, and Mendel was close to crossing them if he hadn’t done so already.

“Careful,” Khodulevich said, and put his index finger to his lips. Don’t say anything that I’ll have to notice – I, or the spies we both know are here. It seemed that Mendel was going to answer him, but his words died unspoken as the Americans came in.

They were a motley group of seven, led by the man who called himself their rabbi – Khodulevich had made inquiries, and he was really a confidence man with a police record in Kansas City, but he’d got an education from somewhere, he was skilled at wheedling enough money from Katz to keep the synagogue running, and he played the part well. He did so now, greeting Khodulevich and gesturing with both hands into the sanctuary.

Old Itzik was there already – he must have come even before Mendel – and with Khodulevich and the Americans, they just made a minyan. They settled to their prayers, all except Mendel who looked on in silent amusement and who shook his head in good humor when the rabbi made his ritual offer of an aliyah. The fog was lifting outside, and the view across the valley lent a sense of peace to the service, but when it was over, the rabbi and Katz motioned the other Americans into a whispered conversation, and even Mendel couldn’t tell what they were talking about.

#

The first of the sailors’ families lived in a shack at the edge of town, at the bottom of the path. The father had already gone to his work as a woodcutter, but the mother was doing the washing in back. She hadn’t heard the news, but something in Khodulevich’s face told her, and even before he started speaking, the tears had started to flow. When he had said the words his duty required, she took him inside and showed him a photograph – a young man of eighteen, proud in his naval uniform. A few letters lay beside it, and now these were all she would have of him. “Think of him sometimes,” she said. “Promise me he will be remembered.”

The second family was two streets away, and they called him a filthy zhid who wasn’t fit to clean their outhouse.

From there, Khodulevich’s route took him into the city. The watch in his pocket told him it was nearing eight o’clock, and the Alexander III Promenade was bustling; the stores were full of customers, carts filled with lumber and mining equipment rumbled down the dirt roadway, and men reeled out of already-open saloons. A few of them saw Khodulevich and straightened up in a hurry; most knew that as long as they stayed peaceable, they weren’t worth his time.

That much was ordinary. But when he passed knots of people talking in the street – some in Russian, most in English – the topic of conversation was always the same. The news of Tsushima spread fast as bad news always did, and by now it had no doubt reached the farthest edges of town; in all likelihood, Khodulevich’s visits to the other sailors’ families would be superfluous.

Not everyone, of course, was taking the news in the same way. The Russians, mostly, were mourning, both for the sailors and their country. Others shut up hastily when Khodulevich approached, which meant that they felt as Mendel did. But the Americans neither mourned nor celebrated in secret; their gestures were emphatic and the rising tone of their voices brimmed over with eagerness.

“The patrol boats are gone,” said a florid-faced outfitter standing outside his warehouse. “There’s nothing between here and the islands – a fleet of fishing boats could get us to Novo-Arkhangelsk.”

The man next to him nodded vigorously. “Take the fort here, get a thousand men across – we could plant the flag within a week.”

“Roosevelt?” asked a third.

“He’ll agree, once it’s done. He’s not the kind to sit and think about it for five years like they did with Hawaii…”

They went on in that vein for some time, taking no notice of Khodulevich – they were either confident they could do nothing to stop him or, more likely, didn’t think he could understand English. But nor did they say enough for Khodulevich to tell if they were serious. None of them struck him as soldiers, and none had anything like a plan; were they really scheming to plant the American flag in the Alyeskan capital, or were they simply hoping for that as they’d no doubt done since they arrived? Would there soon be conversations like this in the Tanana gold fields or the diggings near Fort Nikolaevskaya? Would any of them be more serious than this – were there caches of arms somewhere in town, held against just this kind of happenstance?

Serious or not, these were things the garrison commander should know, and Khodulevich would report to him directly after breakfast.

Breakfast itself was two doors down, at one of the few taverns on the Promenade with signs in both Russian and English. The street was mostly American now but for the public buildings at the far end, but some of the old Russian businesses remained, and one of them was the tavern owned by Khodulevich’s wife. She was behind the bar now, serving coffee and bacon to hungry miners and drinks to thirsty ones, and her broad, dark Tlingit face brightened and grew gentle as she saw him enter.

“Some eggs, Lena?” he said, and she broke three onto the stove as he dragged a stool up to the bar. She didn’t need to ask how he took them, and she knew he wouldn’t want bacon; she also knew how he took his coffee, and that was on the bar even before he sat down.

She, of all people, seemed indifferent to the battle. Like many of her people, she’d been baptized as a child and taught Russian by the missionaries who’d given her a Christian name, but she wasn’t Russian, and she certainly wasn’t American. “The poor young sailors,” she said, but she said that because she was a mother, not because she was a patriot.

“The poor young sailors indeed,” repeated a man at Khodulevich’s right – Katz, he realized. What was Katz doing here? “But at least this will bring the end of the war.”

Khodulevich looked around quickly – Katz had spoken English, but a good half of the Russians in the room would understand, and some would take offense at welcoming the war ending this way. Fortunately, none of them seemed to have heard, but conversations in saloons had a way of becoming louder. “Be careful,” he hissed, much as he had to Mendel two hours before. “Between dreams of revolution and dreams of the Stars and Stripes, it will be easy to get into a fight today and hard to get out of one.”

Katz nodded and rose from his stool, but he wasn’t contrite. “Some fights are worth having,” he said. “Remember that you’re a Jew.”

There was no time to ask Katz what he’d meant before he left, but suddenly Khodulevich knew. In Russia, there were laws restricting where Jews could live and what professions they could follow; there were quotas of boys to be drafted for the army; there were evictions and pogroms. American Jews could live anywhere, work at any job, vote and hold office; many didn’t love them, but they were equal under the law. Katz was trying to recruit him to the American side, which meant that he saw an American coup as something more than a hope – and if someone as rich and well-connected as Katz thought so, then it might well be so.

It was enough to make Khodulevich wonder what his hopes were. He was sixty-three and had fought for Russia for twenty years; his status as a veteran exempted him from most of the restrictive laws, and he’d risen about as far as a retired Jewish cantonist could rise. His life in Alyeska wasn’t a bad one, and he had little love for the rabbis and rich merchants among the Mogilev Jews who’d sent poor boys like him to the army rather than give up their own sons. But he remembered other things he’d seen and stories he’d heard, and just as he’d fought for Russia, he’d fought hard to stay a Jew when the missionaries in the cantonist schools had tried to make a Christian of him. And he'd been cursed as a zhid twice this morning. A country where Jews were free – that called to him in a way that Mendel’s talk of revolution hadn’t.

He had things to think about before he made his report. He needed to talk – to Lena, if no one else. But then there were gunshots and shouting outside. He ran into the street almost gratefully – there were no doubts about what to do now – and at the sight of his uniform, the gathering crowd parted and motioned him to the corpse. .

A corpse, he realized, that he’d seen before. It was the man he’d seen running down the gangway of the Katyusha, and he was dead with three bullets in him.

[to be continued]

Last edited: