You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

1989: A Space Timeline

- Thread starter QueenofScots

- Start date

-

- Tags

- 1980s 1990s space space shuttle

I’m guessing this lasts about two weeks. The next Potus will restore the shuttle. Otherwise you have a load of frustrated astronauts on your hands.

Standart Scenario Shuttle Fleet grounded around 2 years and launch with modified Orbiter

Radical Scenario they Abandon the Shuttle and return to Capsule

Worst case scenario the USA abandon Manned Space Flight close NASA LBJ and Marshal centers, because not needed...

I’m guessing this lasts about two weeks. The next Potus will restore the shuttle. Otherwise you have a load of frustrated astronauts on your hands.

Standart Scenario Shuttle Fleet grounded around 2 years and launch with modified Orbiter

Radical Scenario they Abandon the Shuttle and return to Capsule

Worst case scenario the USA abandon Manned Space Flight close NASA LBJ and Marshal centers, because not needed...

One thing to keep in mind for the time being is that the Soviet Union is still very much a leader in space exploration. Mir has been in orbit for nearly three years, gaining insights into microgravity and materials science. There will have to be some kind of US manned program. The form that takes is uncertain. I do consider an extended return to flight the most likely option, looking at the circumstances, but it is not the only option. 1989 is the namesake of this TL because it was a very unusual year, one that provided unique opportunities and challenges to President Bush.

"I believe that this nation should commit itself, to achieving the goal, before this millennium is out, of landing a man on Mars and returning him, safely, to the Earth." - Whoever Wins in 1988

Atlantis didn't launch until December 1988, so that's still V.P. Bush as President Elect."I believe that this nation should commit itself, to achieving the goal, before this millennium is out, of landing a man on Mars and returning him, safely, to the Earth." - Whoever Wins in 1988

Sorry for the double post, but if the shuttle program is ending in 1989 (not ending, but without a future), I could see three main options for what NASA looks at for a crewed vehicle.

Personally, I think that if you go with a a lifting body, you lock yourself out of the development of AMLS, but a conservative (read, conventional) capsule might not. A biconic/nose first capsule could go either way.

As for lifters, Titan IV and Commercial Titan III could see more payloads, but are fundamentally interim designs that have limited growth, and future as the cost of managing large hypergolic rockets goes up (partially out of safety and environmental concerns, partially because the Titan ICBMs are gone).

Side note: I'd have to look to see at what stage of construction OV-105 was at in January of 1989.

- Some form of Lifting body, probably HL-20 shaped. HL-20 itself is little more than a crew taxi, and only really works in support of a space station. The advantage of HL-20 is that you can probably test launch it on a Titan, and if you get something bigger as your launcher later, NASA had designed a reusable cargo-caboose that would act as the interface between HL-20 and an ET-sized lifter. HL-42, which came later is an enlarged version of the HL-20 shape, and gives you enough space you can do non-station science work. It is also plausible that you could fit an airlock in there for EVA if you wanted to do things like two-launch Hubble repair (one launch with the parts, one with the crew).

- A capsule, either regular conic, or biconic. The advantage of this is that it could support BEO missions a lot easier than a lifting body (no large aerostructure to lift all the way to the moon or beyond). Downside as always is going to be entry loading and to a certain degree down-mass. Here is an NTRS article that talks about a biconic PLS in the 1990-1991 timeframe.

- Shuttle II. the least likely, but something TSTO and reusable comes to mind like the Advanced Manned Launch System. The problem here is that it is the furthest from flight (Operational status by FY2010), but is the closest in capabilities to the shuttle (other than the shorter cargo bay at just 30 feet long).

Personally, I think that if you go with a a lifting body, you lock yourself out of the development of AMLS, but a conservative (read, conventional) capsule might not. A biconic/nose first capsule could go either way.

As for lifters, Titan IV and Commercial Titan III could see more payloads, but are fundamentally interim designs that have limited growth, and future as the cost of managing large hypergolic rockets goes up (partially out of safety and environmental concerns, partially because the Titan ICBMs are gone).

Side note: I'd have to look to see at what stage of construction OV-105 was at in January of 1989.

Last edited:

III: What’s Next? — The White House Perspective

What’s Next? — The White House Perspective

GEORGE BUSH: For many years, our countries have called for the dismantlefication [sic] of the Berlin Wall.

MARGARET THATCHER: Yes, and now it’s finally happened.”

BUSH: Okay… What the hell are we gonna do?

THATCHER: I KNOW! We’ll build more nuclear weapons!

BUSH: More!?

THATCHER: Yes! To counter the threat posed by East… um… East... *spins globe* “Easter Island!

BUSH: What!? Lady, nobody’s stupid enough to fight over a bunch of itsy-bitsy islands!

THATCHER: But we MUST have a deterrent against… *stops globe* Newport Pagnell!

BUSH:“But that’s— that’s just up the road!”

THATCHER: All the more reason to keep our short range nuclear weapons.

BUSH: What the hell for?

THATCHER: Have you tried the all-day breakfast?

—Spitting Image, 1989¹

***

‘What’s next?’ was also a question the United States Department of Defense, and incoming US President George H.W. Bush had to ask. After decades of poor relations with the Soviet Union, and in particular a decade marked by confrontation, the Cold War was over. Though the Soviet Union still existed, its attention was consumed by internal issues, such as the declining economy and the runaway effects of glasnost. Events later in the year would prove catastrophic to the traditional defense worldview. Revolutions shook all of Eastern Europe. The Berlin Wall fell in November, Ceauşescu was shot on Christmas. For the first time in forever, it seemed that democracy was ascendant. Yet, all were future events when Bush took office. Instead, his focus was simply on how the military and its ecosystem of contractors, think tanks, and lobbyists could survive reduced budgets after their Reagan-era heights.

It was at this point that “the peace dividend” entered the political dictionary. It might seem strange now, but in the period between the Cold War and the War in Afghanistan, there were serious hopes— and fears— that the military budget would be slashed significantly, perhaps by 40%. The Air Force in particular had the most to lose. For an example, the B-2 Bomber, designed specifically to penetrate Soviet defenses and deliver dozens of nuclear weapons, flew in July of that year, when it was becoming apparent that it was no longer necessary. The order of 132 had already been cut to just 21. Its stealth coating required an air conditioned hangar, and maintenance cost $3.4 million dollars a month. It had become in Congress a sign of a bloated military. Bush eventually came against the bomber, and similarly could not defend many other projects, but also had to consider the adverse effect the end of the Cold War would bring to aeronautics companies. Lockheed. Martin Marietta. Boeing. There were dozens of companies just like them all across the US. A mixture of legitimate needs, fear of the Russians, and pork had kept these companies healthy since the 40s. Now there were signs that most would have to fold, and leave their employees to fend for themselves in an upcoming recession. A sharp decrease in military spending could transform a mild economic downturn into a full depression.

There was one hope for these companies that George Bush was adamant about when taking office, one he had presented in stump speeches across the country: SDI. The Strategic Defense Initiative, or “Star Wars” as Ted Kennedy liked to call it, was the most grandiose project President Reagan ever proposed. In a move that threatened to destabilize the balance of terror the US and Soviet Union had forged since the Cuban Missile Crisis, the US would construct a system that could shoot down nuclear missiles coming towards the US— every last one of them. Geophysicist Lowell Wood and nuclear physicist Edward Teller were among the top minds set to this task.

Wood and Teller, looking back at previous tries, came up with the winning idea. A proposal in the early 80s was entitled “Smart Rocks.” That proposal had relied upon for centralized orbital ‘Death Stars’ full of guided missiles to shoot down Russian nukes, but these space stations would be easy targets. Not anymore: Smart Rocks was now Brilliant Pebbles. With the microcomputer revolution that took place in the 80s, the missiles could be networked and decentralized, relying only on each other for guidance. Weighing only ten pounds, millions of them could be deployed, covering all the airspace of the world. The concept was redundant and simple enough to make SDI a watertight proposal. Of course, there were many technical challenges, and need of a massive yet cheap rocket to get the pebbles into the air, but these difficulties were not too many to make it past Congress, yet still enough to keep the aforementioned dozens of aerospace companies in business for decades.

A Pebble shedding its areoshell

Perhaps if Bush had a Republican Congress to work with, he would have gotten SDI. But instead, he had Democrats. With the changing geopolitical landscape, and the need to keep the headline “REPUBLICAN PRESIDENT ACHIEVES WORLD PEACE” out of newsstands, SDI went nowhere. Regardless of SDI’s fate, Bush’s priorities had been forced to shift soon after the election. When he was Vice President, he was struck by his meetings with the grieving widows and widowers of the Challenger Seven. Regardless of their own loss, they had called on Bush to make sure that the Shuttle continued. He had to relive this event as President-Elect. Civil spaceflight was not a priority for him as Vice President, neither did he set out to be a “space President.” Yet, it seemed events were conspiring to make him into one, even if he had little idea what that should entail.

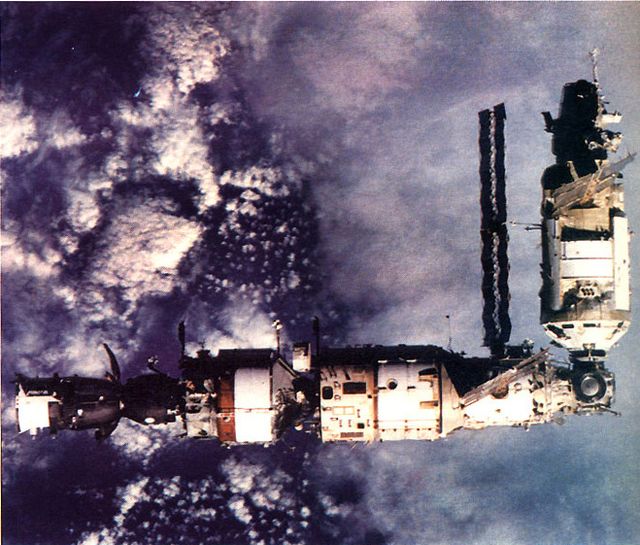

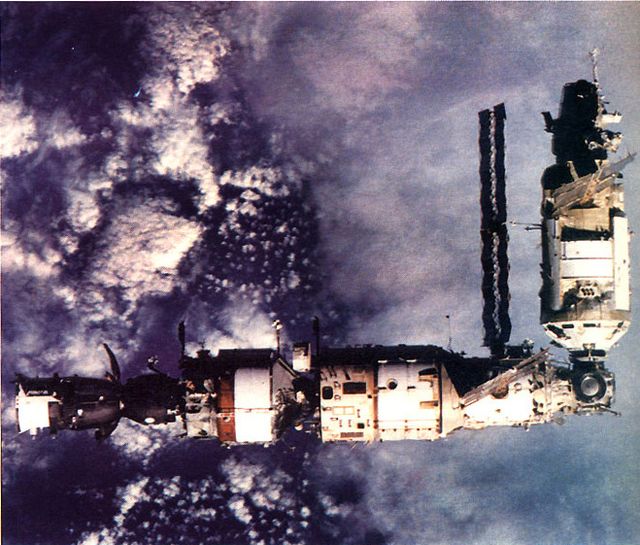

The same day that Atlantis was destroyed, the Mir space station docked with its new Kvant-2 module. As long as the Soviet Union continued to invest in civil spaceflight, so would the United States. A small, but significant, portion of the presidential transition was spent on how to address the future of NASA’s manned flight. To the later embarrassment of the President, Vice President Dan Quayle was a closeted space fanatic. Along with him was RAND Corporation alumnus Mark Albrecht. He initially joined the transition team to provide advice on SDI, but it was with the Atlantis disaster that his rise up the administration ladder began. Albrecht had a background in defense, something that was integral to his opinions on the space program. Albrecht recalls in his memoirs:

Mir with the new Kvant-2

The opinion of the Presidential team, as well as that of former NASA Administrator Thomas Paine, was that NASA had been without proper direction for years. Perhaps what spaceflight needed was its own Joint Chiefs of Staff. From 1958 to 1973, the National Aeronautics and Space Council had presided over and to an extent controlled both military and civil use of space. Congress in the year before implored the winner of the 1988 election to establish a new NASC. Both the Department of Defense and NASA had been reliant on the Shuttle for important payloads, and both would need a new launcher. In changing times, both also needed a coherent vision for their operations in orbit. All parties involved had something to gain in a revived space program, whatever that could be. The decision seemed obvious to the President.

On April 20th, 1989, the National Space Council was formed. Its chair was Dan Quayle, and its Executive Secretary Mark Albrecht. Despite the official blessing, Bush gave the Council little attention. The Council struggled to even find office space in the Old Executive Office Building. Mark Albrecht, while a Beltway creature, was not prepared for working at the White House. Among the issues the deeply inexperienced Albrecht faced, such as what exact role the Council should claim to have, its organizational structure, whether to go with a futuristic letterhead or a traditional one, the color of the carpets, and other extremely important manners, if NASA was actually willing to work for the West Wing instead of Congress seemed to be forgotten. Thankfully, a selection had already been made for Administrator of NASA that would help the Space Council find its footing, and would pay dividends in the years to come.

________

¹OTL quote.

²OTL memoirs. Albrecht, Mark. Falling Back to Earth: a First Hand Account of the Great Space Race and the End of the Cold War. New Media Books, 2011.

GEORGE BUSH: For many years, our countries have called for the dismantlefication [sic] of the Berlin Wall.

MARGARET THATCHER: Yes, and now it’s finally happened.”

BUSH: Okay… What the hell are we gonna do?

THATCHER: I KNOW! We’ll build more nuclear weapons!

BUSH: More!?

THATCHER: Yes! To counter the threat posed by East… um… East... *spins globe* “Easter Island!

BUSH: What!? Lady, nobody’s stupid enough to fight over a bunch of itsy-bitsy islands!

THATCHER: But we MUST have a deterrent against… *stops globe* Newport Pagnell!

BUSH:“But that’s— that’s just up the road!”

THATCHER: All the more reason to keep our short range nuclear weapons.

BUSH: What the hell for?

THATCHER: Have you tried the all-day breakfast?

—Spitting Image, 1989¹

***

‘What’s next?’ was also a question the United States Department of Defense, and incoming US President George H.W. Bush had to ask. After decades of poor relations with the Soviet Union, and in particular a decade marked by confrontation, the Cold War was over. Though the Soviet Union still existed, its attention was consumed by internal issues, such as the declining economy and the runaway effects of glasnost. Events later in the year would prove catastrophic to the traditional defense worldview. Revolutions shook all of Eastern Europe. The Berlin Wall fell in November, Ceauşescu was shot on Christmas. For the first time in forever, it seemed that democracy was ascendant. Yet, all were future events when Bush took office. Instead, his focus was simply on how the military and its ecosystem of contractors, think tanks, and lobbyists could survive reduced budgets after their Reagan-era heights.

It was at this point that “the peace dividend” entered the political dictionary. It might seem strange now, but in the period between the Cold War and the War in Afghanistan, there were serious hopes— and fears— that the military budget would be slashed significantly, perhaps by 40%. The Air Force in particular had the most to lose. For an example, the B-2 Bomber, designed specifically to penetrate Soviet defenses and deliver dozens of nuclear weapons, flew in July of that year, when it was becoming apparent that it was no longer necessary. The order of 132 had already been cut to just 21. Its stealth coating required an air conditioned hangar, and maintenance cost $3.4 million dollars a month. It had become in Congress a sign of a bloated military. Bush eventually came against the bomber, and similarly could not defend many other projects, but also had to consider the adverse effect the end of the Cold War would bring to aeronautics companies. Lockheed. Martin Marietta. Boeing. There were dozens of companies just like them all across the US. A mixture of legitimate needs, fear of the Russians, and pork had kept these companies healthy since the 40s. Now there were signs that most would have to fold, and leave their employees to fend for themselves in an upcoming recession. A sharp decrease in military spending could transform a mild economic downturn into a full depression.

There was one hope for these companies that George Bush was adamant about when taking office, one he had presented in stump speeches across the country: SDI. The Strategic Defense Initiative, or “Star Wars” as Ted Kennedy liked to call it, was the most grandiose project President Reagan ever proposed. In a move that threatened to destabilize the balance of terror the US and Soviet Union had forged since the Cuban Missile Crisis, the US would construct a system that could shoot down nuclear missiles coming towards the US— every last one of them. Geophysicist Lowell Wood and nuclear physicist Edward Teller were among the top minds set to this task.

Wood and Teller, looking back at previous tries, came up with the winning idea. A proposal in the early 80s was entitled “Smart Rocks.” That proposal had relied upon for centralized orbital ‘Death Stars’ full of guided missiles to shoot down Russian nukes, but these space stations would be easy targets. Not anymore: Smart Rocks was now Brilliant Pebbles. With the microcomputer revolution that took place in the 80s, the missiles could be networked and decentralized, relying only on each other for guidance. Weighing only ten pounds, millions of them could be deployed, covering all the airspace of the world. The concept was redundant and simple enough to make SDI a watertight proposal. Of course, there were many technical challenges, and need of a massive yet cheap rocket to get the pebbles into the air, but these difficulties were not too many to make it past Congress, yet still enough to keep the aforementioned dozens of aerospace companies in business for decades.

A Pebble shedding its areoshell

The same day that Atlantis was destroyed, the Mir space station docked with its new Kvant-2 module. As long as the Soviet Union continued to invest in civil spaceflight, so would the United States. A small, but significant, portion of the presidential transition was spent on how to address the future of NASA’s manned flight. To the later embarrassment of the President, Vice President Dan Quayle was a closeted space fanatic. Along with him was RAND Corporation alumnus Mark Albrecht. He initially joined the transition team to provide advice on SDI, but it was with the Atlantis disaster that his rise up the administration ladder began. Albrecht had a background in defense, something that was integral to his opinions on the space program. Albrecht recalls in his memoirs:

It took very little time to come to two central observations about the state of the US space enterprise. First, defense and intelligence space programs were generally the result of disciplined processes of validated requirements from operational commands, tested and refined by a competitive internal resource allocation process … NASA was a jumble of activities that was a constant and dynamic balance of interests. ²

Mir with the new Kvant-2

On April 20th, 1989, the National Space Council was formed. Its chair was Dan Quayle, and its Executive Secretary Mark Albrecht. Despite the official blessing, Bush gave the Council little attention. The Council struggled to even find office space in the Old Executive Office Building. Mark Albrecht, while a Beltway creature, was not prepared for working at the White House. Among the issues the deeply inexperienced Albrecht faced, such as what exact role the Council should claim to have, its organizational structure, whether to go with a futuristic letterhead or a traditional one, the color of the carpets, and other extremely important manners, if NASA was actually willing to work for the West Wing instead of Congress seemed to be forgotten. Thankfully, a selection had already been made for Administrator of NASA that would help the Space Council find its footing, and would pay dividends in the years to come.

________

¹OTL quote.

²OTL memoirs. Albrecht, Mark. Falling Back to Earth: a First Hand Account of the Great Space Race and the End of the Cold War. New Media Books, 2011.

Last edited:

Well, Dan Quayle has one thing I like about him (his vice-presidency was a disaster overall--spelling potato wrong (1), condemning Murphy Brown for glorifying single motherhood, etc.)…

Good update...

(1) Which prompted the kid to say on David Letterman "Do you have to go to college to be vice-president?"; my late mother's theory was that he picked Quayle because he reminded him of his son...

Good update...

(1) Which prompted the kid to say on David Letterman "Do you have to go to college to be vice-president?"; my late mother's theory was that he picked Quayle because he reminded him of his son...

Don't worry, there's an installment coming. I've decided to move this TL's update time to earlier, and on a Monday, to better accommodate readers in the eastern US.

IV: What’s Next? — NASA’s Persective

What’s Next? — NASA’s Persective

Daniel Goldin, the new NASA administrator

Daniel Goldin was a surprise pick for the role of NASA Administrator, relatively obscure to those knowledgeable with the program. Early on in his career, he worked at NASA, but then left to join the public sector. A manager at TRW, he advanced quickly through the ranks. He impressed both the Vice President and Chief of Staff Craig Fuller in preliminary meetings, demonstrating the charisma, force of will, and forward thinking mentality the Administration was looking for. A registered Democrat, he soared through his hearings in May. However, he had a difficult job ahead: healing a deeply divided agency.

Just a couple of years after the loss of Challenger, the loss of Atlantis had brought NASA’s morale to all time lows. However, NASA is not a monolithic organization, but instead has always been a motley collection of institutions. While the purely areonautical field centers saw few changes following the incident, the most affected, and those most instrumental to understanding NASA’s space history, were the Johnson Space Center (JSC), and the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC).

Established in 1961 as the Manned Spacecraft Center, the Johnson Space Center was the linchpin of the Shuttle program. It was the “Houston” that astronauts relied upon for guidance, and where they lived during training. Dives into the one of a kind Weightless Environment Training Facility prepared them for Shuttle operations, and flights in T-38s prepared them for landings. It was here that Space Station Freedom was born, the planned destination for the Shuttle. How could an organization so devoted to the Shuttle deal with its oncoming absence? JSC was one of the more daring of the centers, willing to take risks and lead revolutions in spaceflight. This changed after Challenger, once it was realized that risk-taking had turned into criminal negligence. It was from then on dedicated to preserving the Space Shuttle, and its eventual destination Space Station Freedom, from harm. Despite it being the selling point of the program, commercial payloads would no longer fly on the Shuttle. Neither would Lewis Space Center’s Shuttle Centaur, a high performance liquid hydrogen rocket stage, be allowed onboard. With Freedom, the center gained a reputation as “Fortress JSC,” where no outside ideas were allowed. The projected cost of the station, at first $8 billion, had ballooned to $30 billion, scientific value dropping with every revision. Ultimately, it wouldn't matter With the Atlantis disaster, JSC had lost all the political capital it had invested since 1986. The final Atlantis report, overseen by an independent tribunal, named JSC managers’ normalization of non-catastrophic failures over time as the overarching cause of both Challenger and Atlantis. Presidential relations deteriorated. Once the most powerful field center, it was now increasingly isolated.

When Wehrner von Braun entered the United States in 1945, he set to work making missiles at the US Army’s Ordnance Corps. One of the Army bases involved, Alabama’s Redstone Arsenal, would become the Marshall Space Flight Center. Marshall was usually the conservative voice when it came to the planning of major missions, a heritage of its German roots. The loss of Atlantis weighed heavily on the men in Huntsville: twice now, the Shuttle’s Solid Rocket Boosters, their boosters, had claimed the lives of crew. Yet, repercussions for this seemed not to materialize. It had been the NASA office in Washington, after all, that dictated the use of solids over Marshall’s preferred liquid boosters. In NASA’s darkest hour, Marshall saw its influence grow relative to Johnson’s.

Regardless, both Marshall and Johnson had to move on. Getting the Shuttle back up and running was the first priority. Daniel Goldin’s most striking move in his first month of office was a speech at MSFC. Stressing the need to see the final missions of the STS program be its best, Goldin ended the speech with the words, “if we’re not going to do it right, why the hell are we doing it all?” Engineers set to the task of making a doomed program work as smoothly as ever. Hundreds of changes were made to the Shuttle, especially to the External Tank. In addition, a full inspection of the tiling would be made on each flight after entering orbit.

The payloads were also given special attention. One flight was reserved for the Department of Defense. Another would be to recover the material science satellite LDEF. That left just two payloads that would remain on the Shuttle, instead of being moved to the Titan IV: The Hubble Space Telescope, and the out of the ecliptic mission Ulysses. The regimens of tests designed to make sure these payload would work were fruitful: a minute flaw was detected in Hubble’s main mirror that could have crippled it. The backup Kodak mirror was prepared instead. The last flight of Columbia would be on September 12th, 1990, with Hubble aboard.

Yet, the long terms future of the agency was still undecided. What would be the successor to the Shuttle? One of the first avenues pursued was Soviet-American cooperation. The two nations were already collaborating on unmanned Mars missions, the upcoming Mars Observer providing the relay that a Soviet lander would rely on. Preliminary studies and unofficial overtures were made considering the possibility of American use of Mir. Perhaps American seats on Soyuz could be secured by providing direct material support to the program. Ultimately, Presidential influence would lead the agency in a different, albeit related direction.

Daniel Goldin, the new NASA administrator

Daniel Goldin was a surprise pick for the role of NASA Administrator, relatively obscure to those knowledgeable with the program. Early on in his career, he worked at NASA, but then left to join the public sector. A manager at TRW, he advanced quickly through the ranks. He impressed both the Vice President and Chief of Staff Craig Fuller in preliminary meetings, demonstrating the charisma, force of will, and forward thinking mentality the Administration was looking for. A registered Democrat, he soared through his hearings in May. However, he had a difficult job ahead: healing a deeply divided agency.

Just a couple of years after the loss of Challenger, the loss of Atlantis had brought NASA’s morale to all time lows. However, NASA is not a monolithic organization, but instead has always been a motley collection of institutions. While the purely areonautical field centers saw few changes following the incident, the most affected, and those most instrumental to understanding NASA’s space history, were the Johnson Space Center (JSC), and the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC).

Established in 1961 as the Manned Spacecraft Center, the Johnson Space Center was the linchpin of the Shuttle program. It was the “Houston” that astronauts relied upon for guidance, and where they lived during training. Dives into the one of a kind Weightless Environment Training Facility prepared them for Shuttle operations, and flights in T-38s prepared them for landings. It was here that Space Station Freedom was born, the planned destination for the Shuttle. How could an organization so devoted to the Shuttle deal with its oncoming absence? JSC was one of the more daring of the centers, willing to take risks and lead revolutions in spaceflight. This changed after Challenger, once it was realized that risk-taking had turned into criminal negligence. It was from then on dedicated to preserving the Space Shuttle, and its eventual destination Space Station Freedom, from harm. Despite it being the selling point of the program, commercial payloads would no longer fly on the Shuttle. Neither would Lewis Space Center’s Shuttle Centaur, a high performance liquid hydrogen rocket stage, be allowed onboard. With Freedom, the center gained a reputation as “Fortress JSC,” where no outside ideas were allowed. The projected cost of the station, at first $8 billion, had ballooned to $30 billion, scientific value dropping with every revision. Ultimately, it wouldn't matter With the Atlantis disaster, JSC had lost all the political capital it had invested since 1986. The final Atlantis report, overseen by an independent tribunal, named JSC managers’ normalization of non-catastrophic failures over time as the overarching cause of both Challenger and Atlantis. Presidential relations deteriorated. Once the most powerful field center, it was now increasingly isolated.

When Wehrner von Braun entered the United States in 1945, he set to work making missiles at the US Army’s Ordnance Corps. One of the Army bases involved, Alabama’s Redstone Arsenal, would become the Marshall Space Flight Center. Marshall was usually the conservative voice when it came to the planning of major missions, a heritage of its German roots. The loss of Atlantis weighed heavily on the men in Huntsville: twice now, the Shuttle’s Solid Rocket Boosters, their boosters, had claimed the lives of crew. Yet, repercussions for this seemed not to materialize. It had been the NASA office in Washington, after all, that dictated the use of solids over Marshall’s preferred liquid boosters. In NASA’s darkest hour, Marshall saw its influence grow relative to Johnson’s.

Regardless, both Marshall and Johnson had to move on. Getting the Shuttle back up and running was the first priority. Daniel Goldin’s most striking move in his first month of office was a speech at MSFC. Stressing the need to see the final missions of the STS program be its best, Goldin ended the speech with the words, “if we’re not going to do it right, why the hell are we doing it all?” Engineers set to the task of making a doomed program work as smoothly as ever. Hundreds of changes were made to the Shuttle, especially to the External Tank. In addition, a full inspection of the tiling would be made on each flight after entering orbit.

The payloads were also given special attention. One flight was reserved for the Department of Defense. Another would be to recover the material science satellite LDEF. That left just two payloads that would remain on the Shuttle, instead of being moved to the Titan IV: The Hubble Space Telescope, and the out of the ecliptic mission Ulysses. The regimens of tests designed to make sure these payload would work were fruitful: a minute flaw was detected in Hubble’s main mirror that could have crippled it. The backup Kodak mirror was prepared instead. The last flight of Columbia would be on September 12th, 1990, with Hubble aboard.

Yet, the long terms future of the agency was still undecided. What would be the successor to the Shuttle? One of the first avenues pursued was Soviet-American cooperation. The two nations were already collaborating on unmanned Mars missions, the upcoming Mars Observer providing the relay that a Soviet lander would rely on. Preliminary studies and unofficial overtures were made considering the possibility of American use of Mir. Perhaps American seats on Soyuz could be secured by providing direct material support to the program. Ultimately, Presidential influence would lead the agency in a different, albeit related direction.

Last edited:

So then, I assume the USSR doesn't dissolve, instead it's a "near miss" scenario. The most logical outcome is that the rooskies pull the plug on Buran right away, seeing no reason to continue such a costly program when there is no reason to. The way I see it, the most likely short term situation is not dissimilar to today: Americans going up in Soyuz, while a capsule-based shuttle replacement is being developed. It's more likely than not that the shuttle replacement will be similar to Orion, in both design and capabilities. This is of course all speculation, but presumably, with no soviet dissolution, a more Mir-2 oriented ISS is launched at the end of the millennium, instead of the mashup of Freedom and Mir-2 that we ended up getting, and BEO missions start up during the new millennium.

So then, I assume the USSR doesn't dissolve, instead it's a "near miss" scenario. The most logical outcome is that the rooskies pull the plug on Buran right away, seeing no reason to continue such a costly program when there is no reason to. The way I see it, the most likely short term situation is not dissimilar to today: Americans going up in Soyuz, while a capsule-based shuttle replacement is being developed. It's more likely than not that the shuttle replacement will be similar to Orion, in both design and capabilities. This is of course all speculation, but presumably, with no soviet dissolution, a more Mir-2 oriented ISS is launched at the end of the millennium, instead of the mashup of Freedom and Mir-2 that we ended up getting, and BEO missions start up during the new millennium.

Sorry if I've created that impression, but the part about US-Soviet cooperation is completely OTL. I'll be covering the Russian side of things in detail another time, but 1989 was the peak of Soviet-American cooperation, helped in part by Carl Sagan.

This is a big change that sort of gets sidelined by the rest of the post. Fuller was Bush's CoS while he was VP, and IIRC, CoS in the White House was the only job that would have kept him in government service.Chief of Staff Craig Fuller

The payloads were also given special attention. One flight was reserved for the Department of Defense. Another would be to recover the material science satellite LDEF. That left just two payloads that would remain on the Shuttle, instead of being moved to the Titan IV: The Hubble Space Telescope, and the Jupiter orbiter Galileo. The regimens of tests designed to make sure these payload would work were fruitful: a minute flaw was detected in Hubble’s main mirror that could have crippled it. The backup Kodak mirror was prepared instead. The last flight of Columbia would be on September 12th, 1990, with Hubble aboard.

So, a DoD launch (MAGNUM, MISTY, SDS, or SDS/Prowler), LDEF return (which probably also sees Syncom IV-F5 as STS-32 flew historically), Galileo, and Hubble. Getting the DoD down to just one flight is not going to be easy. The Galileo and the Ulysses teams would certainly have fought over who got on the shuttle. Ulysses would have a pair of advantages in this: It is an international program and getting it launched sooner is better which ties into the second part - The Ulysses stack (IUS + PAM-S + Ulysses) is light enough to go direct to Jupiter from the shuttle, where as Galileo needs to do VEEGA to get there.

This is a big change that sort of gets sidelined by the rest of the post. Fuller was Bush's CoS while he was VP, and IIRC, CoS in the White House was the only job that would have kept him in government service.

So, a DoD launch (MAGNUM, MISTY, SDS, or SDS/Prowler), LDEF return (which probably also sees Syncom IV-F5 as STS-32 flew historically), Galileo, and Hubble. Getting the DoD down to just one flight is not going to be easy. The Galileo and the Ulysses teams would certainly have fought over who got on the shuttle. Ulysses would have a pair of advantages in this: It is an international program and getting it launched sooner is better which ties into the second part - The Ulysses stack (IUS + PAM-S + Ulysses) is light enough to go direct to Jupiter from the shuttle, where as Galileo needs to do VEEGA to get there.

Recognized. Changing to Ulysses.

So Titan III and IV become backbone of NASA and USAF launch systems after phase out of STS.

There were allot of improvement study by Martin Marietta to get more payload into space with Titan rocket.

like Composite structures skirt for Core and Second stage

or replace the Second stage with new Lox/Lh2 that use ALS deviate engine, payload 75000 lbs.

or Liquid rocket booster build from core stage with four engines

Most radical proposal was to replace the Core stage with all new Lox/Lh2 core

This "Titan V" would be more like Ariane 5, with 2-4 LRB or Solids payload 100000 lbs. to 130000 lbs.

But main Question is: Will NASA and USAF getting the Budget for necessary changes to come ?

And there another monster lurking around the corner: Bush Space Exploration Initiative (SEI)

That was gigantic program needed 30 years to complete in 3 phase

1. Space Station 2. Moon base 3. Manned Flight to Mars

with price tag of 500 billion USDollars (or 16 billion/year)

Capitol Hill on that "no way, Jose"

There were allot of improvement study by Martin Marietta to get more payload into space with Titan rocket.

like Composite structures skirt for Core and Second stage

or replace the Second stage with new Lox/Lh2 that use ALS deviate engine, payload 75000 lbs.

or Liquid rocket booster build from core stage with four engines

Most radical proposal was to replace the Core stage with all new Lox/Lh2 core

This "Titan V" would be more like Ariane 5, with 2-4 LRB or Solids payload 100000 lbs. to 130000 lbs.

But main Question is: Will NASA and USAF getting the Budget for necessary changes to come ?

And there another monster lurking around the corner: Bush Space Exploration Initiative (SEI)

That was gigantic program needed 30 years to complete in 3 phase

1. Space Station 2. Moon base 3. Manned Flight to Mars

with price tag of 500 billion USDollars (or 16 billion/year)

Capitol Hill on that "no way, Jose"

So Titan III and IV become backbone of NASA and USAF launch systems after phase out of STS.

There were allot of improvement study by Martin Marietta to get more payload into space with Titan rocket.

like Composite structures skirt for Core and Second stage

or replace the Second stage with new Lox/Lh2 that use ALS deviate engine, payload 75000 lbs.

or Liquid rocket booster build from core stage with four engines

Most radical proposal was to replace the Core stage with all new Lox/Lh2 core

This "Titan V" would be more like Ariane 5, with 2-4 LRB or Solids payload 100000 lbs. to 130000 lbs.

IOTL the Titan IV was approved either right after or shortly before Challenger, entering service in 1988.

It's problem is that it's a hugely inflexible LV with a total dependence on its 7-seg SRBs just to get off the ground, so getting a non-N2O4/A50 LV into service I can see as being a USAF priority, as well as a NASA one. Especially given that STS ITTL is pretty much finished.

But main Question is: Will NASA and USAF getting the Budget for necessary changes to come ?

And there another monster lurking around the corner: Bush Space Exploration Initiative (SEI)

That was gigantic program needed 30 years to complete in 3 phase

1. Space Station 2. Moon base 3. Manned Flight to Mars

with price tag of 500 billion USDollars (or 16 billion/year)

Capitol Hill on that "no way, Jose"

SEI I can't see happening here.

1 - Dan Goldin taking the NASA Reins sooner, and I haven't forgotten his motto of Faster-Better-Cheaper, though the SEI Debacle could well have played a role there...

2 - Two LOC Disasters in less than 3 years? Good luck trying anything remotely that ambitious so soon after

3 - A safe means (especially compared to STS) of getting a crew into Space I think would be an overriding priority item, certainly before they'd be allowed to even think about what next regarding BEO

4 - And $450,000,000,000 in 1989 USD? Don't count on it

Another thing I can see this affecting is Hermes, the ESA mini-Shuttle which was still being designed at this time. What happens to it, how that in turn affects the planned Ariane V ITTL, who knows?

Perhaps American seats on Soyuz could be secured by providing direct material support to the program. Ultimately, Presidential influence would lead the agency in a different, albeit related direction.

Hmm... Clearly the US is going to buy Buran for its own use.

Seriously, maybe there'll be a Zenit derived booster for the Shuttle Mk 2

Has this timeline been cancelled, then?Apologies. No update this week due to the start of the school year.

Edit: Nevermind, QueenofScots cancelled their own account.

Last edited:

Share: