Winds of Change - part one

Libau and Windau vied with Riga and Königsberg to be the foremost ports on the Eastern side of the Baltic. Of the four, Riga was the most formidable city, the others being relative upstarts. Riga had the natural advantage of being at the mouth of the Düna river, a convenient trade route for goods from Lithuania and the central parts of Russia. Goods that could as easily go overland Jakob eagerly encouraged to pass overland to meet the Baltic at Libau or Windau instead. Further west, the river Windau that gave the Couronian port its name was already convenient for some Lithuanian goods headed for the Baltic, though the Memel river further south was a stronger conduit for trade out of Lithuania - trade that would then pass via Königsberg or Memel (or Memelburg).

Jakob had chipped away at Riga's share of Baltic trade. Memel and Königsberg were ruled by his brother-in-law, and when it came to matters Baltic and matters trade, he got along rather well with his brother-in-law. So neither Prussia nor Courland undermined each other. Prussia/Brandenburg focused somewhat on being pre-eminent in German trade, or broader European trade. Courland focused on developing industry both as its own reward and as a way of supporting its profitable colonial ventures.

Libau was already the most active port for one thing, though: mail. The Martin Maritime Academy voraciously drew letters, books, and learned people from across Europe, sending others back out. The "Invisible College" of learned folk across Europe, or whatever those smart letter-writers called it, either brought letters in or letters out, and that brought more people in, who sent and received still more letters, which drew more people....

The thing was that Courland's high and still-growing religious tolerance, coupled with Libau's tolerance for the most controversial or fanciful ideas, led to a potent blend of intellect and risk. Risk and intellect each had a way of amplifying the other.

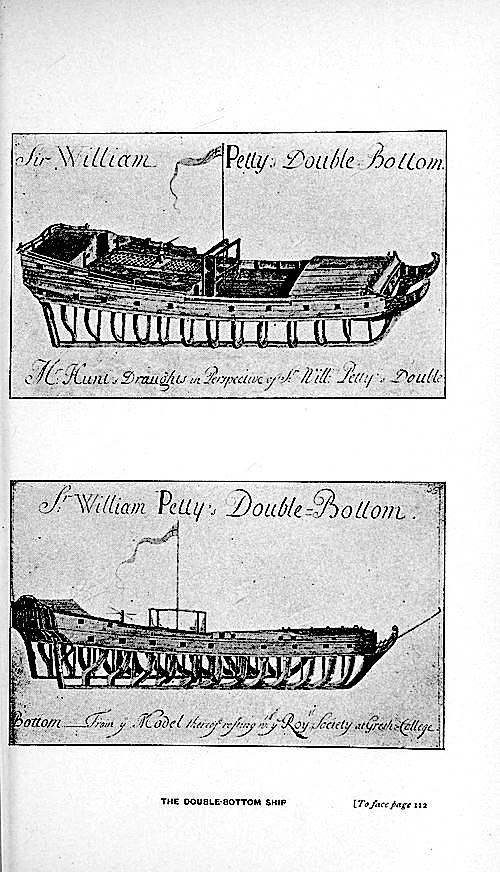

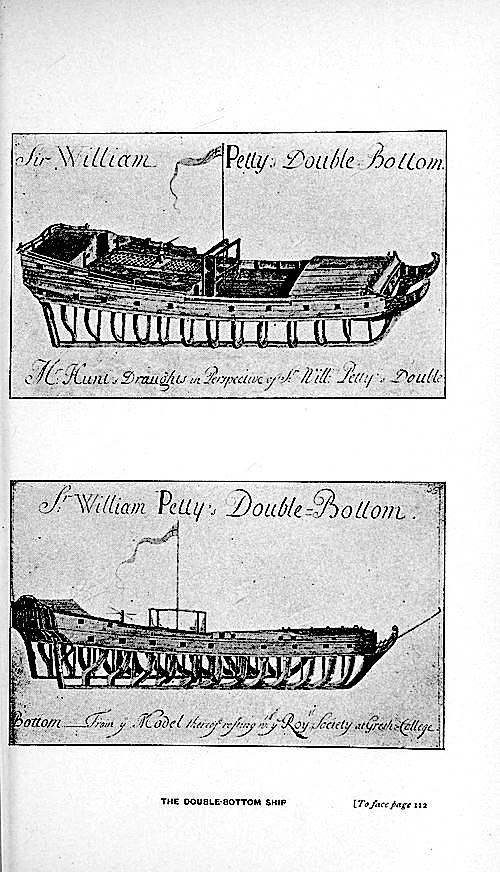

William Petty's ideas came in first via mail from England (or Ireland) to Libau, initially on economic matters in correspondence with Jakob and others, and later on any matters for which his wide-ranging brilliance found a worthy pen-pal.

Today, Jakob was looking at one product of that correspondence. Petty's wide-ranging ideas saw Libau shipwrights (and academy students) build the Zwillingkufe, a third or fourth or fifth iteration of a ship design based on one Petty had included in a wide-ranging missive about ships, wind, water resistance, economics, accompanied by some work-in-progress mathematical formulae on each topic.

The first iteration or two were miniature models, fairly faithful to Petty's hull design, built entirely by academy students and tested - unmanned - in the Libau lake. By now, the students' zeal for maximizing whatever features might prove most measurably impactful about the two-hull design had already evolved it into still greater an oddity. The third Zwillingkufe was neither a scaled-up version of the first two unmanned miniatures, nor a scaled-down version of the two-decked vessel in Petty's design. On a long visit to Libau, to Jakob and the Academy, Petty himself needed a moment to process how the changes might affect the craft.

The third ZK (Petty avoided mangling the full name) was out of all proportion with his Double-Bottom idea. The ship was much smaller (he'd intended a gun deck and main deck, but the ZK's deck looked scarcely bigger than a large raft. Petty hadn't focused on sails, because the novel idea was about the hulls and their minimal contact and resistance against the water. After shrinking the scale of the ship from his original design, these mad Courlanders then equipped the ZK with the largest lateen sail they thought it could manage, simply because it was the best way to amplify the testable difference between this design and a single-hull ship. It was still only testing the ideas, but testing different aspects of them.

But oh, what testing.

It had already outraced a monohull with a matching sail, and was now frequently seen zipping around near Libau, advertising Couronian endeavour or madness. Sailors on inbound ships respected its speed, sailors based in Libau saw the abusive sailing it endured in the name of testing and mistook it for deficiency, and shook their heads.

The fourth and fifth ZKs followed, with growing ambition and scale. Watching both grow in the shipyard, enough sailors kept scoffing at the double hulls for it to influence the design - if you couldn't get enough sailors enthusiastic about sailing it, then it needed to be able to handled by a smaller crew. Square-rigging was out, as that took more men. The biggest ZK would be rigged fore-and-aft on both masts, without a topsail, and with a jib as the only staysail never to leave the design. As a ship meant to not tip all that much, its main deck was still lower than it might have been as a monohull. The shipwrights were working on a modest gun deck now - in Courland, passing up an opportunity to experiment was counted as a failure of missed opportunity.

While work continued on that, the fourth ZK was out on the water too. Two-masted like her under-construction sister, but smaller and without guns, designed for up to 4 sails and as few as two sailors.

Jakob, ever impatient for innovation to be taken up and made use of, undercut the sailors' resistance most simply: he asked for ten of the most vocally skeptical sailors in Libau to be invited to tested to serve as his personal crew for a coming voyage on the Baltic, with a bonus in pay to those selected.

When Jakob then selected the fourth ZK as the ship on which he would travel, the academy students suddenly found the third ZK unavailable for their joy rides around the harbour.

But they consoled themselves watching the feats the professional sailors managed on their craft. The sailors had watched the students sail it, now the students watched the sailors. And that reversal of roles gave the ship a nickname: Der Zweifler (the Skeptic), punning on the ship's two hulls (zwei Rümpfe).

- - -

Part two will be a conversation at the destination of Jakob's voyage on Der Zweifler. First correct guess as to the destination gets a character named after them (I reserve the right to get creative if their handle is less suited to a name).

Anyone interested in speculating as to the value of a ship that is effectively a catamaran-hulled schooner, feel free. Courland and I make this stuff mostly for fun, then see where it goes.

Libau and Windau vied with Riga and Königsberg to be the foremost ports on the Eastern side of the Baltic. Of the four, Riga was the most formidable city, the others being relative upstarts. Riga had the natural advantage of being at the mouth of the Düna river, a convenient trade route for goods from Lithuania and the central parts of Russia. Goods that could as easily go overland Jakob eagerly encouraged to pass overland to meet the Baltic at Libau or Windau instead. Further west, the river Windau that gave the Couronian port its name was already convenient for some Lithuanian goods headed for the Baltic, though the Memel river further south was a stronger conduit for trade out of Lithuania - trade that would then pass via Königsberg or Memel (or Memelburg).

Jakob had chipped away at Riga's share of Baltic trade. Memel and Königsberg were ruled by his brother-in-law, and when it came to matters Baltic and matters trade, he got along rather well with his brother-in-law. So neither Prussia nor Courland undermined each other. Prussia/Brandenburg focused somewhat on being pre-eminent in German trade, or broader European trade. Courland focused on developing industry both as its own reward and as a way of supporting its profitable colonial ventures.

Libau was already the most active port for one thing, though: mail. The Martin Maritime Academy voraciously drew letters, books, and learned people from across Europe, sending others back out. The "Invisible College" of learned folk across Europe, or whatever those smart letter-writers called it, either brought letters in or letters out, and that brought more people in, who sent and received still more letters, which drew more people....

The thing was that Courland's high and still-growing religious tolerance, coupled with Libau's tolerance for the most controversial or fanciful ideas, led to a potent blend of intellect and risk. Risk and intellect each had a way of amplifying the other.

William Petty's ideas came in first via mail from England (or Ireland) to Libau, initially on economic matters in correspondence with Jakob and others, and later on any matters for which his wide-ranging brilliance found a worthy pen-pal.

Today, Jakob was looking at one product of that correspondence. Petty's wide-ranging ideas saw Libau shipwrights (and academy students) build the Zwillingkufe, a third or fourth or fifth iteration of a ship design based on one Petty had included in a wide-ranging missive about ships, wind, water resistance, economics, accompanied by some work-in-progress mathematical formulae on each topic.

The first iteration or two were miniature models, fairly faithful to Petty's hull design, built entirely by academy students and tested - unmanned - in the Libau lake. By now, the students' zeal for maximizing whatever features might prove most measurably impactful about the two-hull design had already evolved it into still greater an oddity. The third Zwillingkufe was neither a scaled-up version of the first two unmanned miniatures, nor a scaled-down version of the two-decked vessel in Petty's design. On a long visit to Libau, to Jakob and the Academy, Petty himself needed a moment to process how the changes might affect the craft.

The third ZK (Petty avoided mangling the full name) was out of all proportion with his Double-Bottom idea. The ship was much smaller (he'd intended a gun deck and main deck, but the ZK's deck looked scarcely bigger than a large raft. Petty hadn't focused on sails, because the novel idea was about the hulls and their minimal contact and resistance against the water. After shrinking the scale of the ship from his original design, these mad Courlanders then equipped the ZK with the largest lateen sail they thought it could manage, simply because it was the best way to amplify the testable difference between this design and a single-hull ship. It was still only testing the ideas, but testing different aspects of them.

But oh, what testing.

It had already outraced a monohull with a matching sail, and was now frequently seen zipping around near Libau, advertising Couronian endeavour or madness. Sailors on inbound ships respected its speed, sailors based in Libau saw the abusive sailing it endured in the name of testing and mistook it for deficiency, and shook their heads.

The fourth and fifth ZKs followed, with growing ambition and scale. Watching both grow in the shipyard, enough sailors kept scoffing at the double hulls for it to influence the design - if you couldn't get enough sailors enthusiastic about sailing it, then it needed to be able to handled by a smaller crew. Square-rigging was out, as that took more men. The biggest ZK would be rigged fore-and-aft on both masts, without a topsail, and with a jib as the only staysail never to leave the design. As a ship meant to not tip all that much, its main deck was still lower than it might have been as a monohull. The shipwrights were working on a modest gun deck now - in Courland, passing up an opportunity to experiment was counted as a failure of missed opportunity.

While work continued on that, the fourth ZK was out on the water too. Two-masted like her under-construction sister, but smaller and without guns, designed for up to 4 sails and as few as two sailors.

Jakob, ever impatient for innovation to be taken up and made use of, undercut the sailors' resistance most simply: he asked for ten of the most vocally skeptical sailors in Libau to be invited to tested to serve as his personal crew for a coming voyage on the Baltic, with a bonus in pay to those selected.

When Jakob then selected the fourth ZK as the ship on which he would travel, the academy students suddenly found the third ZK unavailable for their joy rides around the harbour.

But they consoled themselves watching the feats the professional sailors managed on their craft. The sailors had watched the students sail it, now the students watched the sailors. And that reversal of roles gave the ship a nickname: Der Zweifler (the Skeptic), punning on the ship's two hulls (zwei Rümpfe).

- - -

Part two will be a conversation at the destination of Jakob's voyage on Der Zweifler. First correct guess as to the destination gets a character named after them (I reserve the right to get creative if their handle is less suited to a name).

Anyone interested in speculating as to the value of a ship that is effectively a catamaran-hulled schooner, feel free. Courland and I make this stuff mostly for fun, then see where it goes.