Probably. But without Posen and the West side of the Rhine river.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The New Order: A Successful Selim III

- Thread starter Vinization

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 20 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 13: The Congress of Frankfurt Part 14: The Spectre of Revolution Part 15: Papers and Muskets Map: Europe after the Congress of Frankfurt Part 16: Carrots, Sticks and Daggers Part 17: A Beacon of Hope and Fear Part 18: An Eagle Reborn Part 19: Death of an Empire, (Re) Birth of AnotherQuestion is the Spanish american colonies already lost? Like the spanish army has proven well here, so more legitimacy here etc, Also with the Napoleonic wars over can spain now send the most of the army over to fight the rebel? or is it too late now?

However, this post by Meordal also details how Spain might keep her colonies, had the Bourbon Kings been more competent.There is a great post by Sarthaka where he basically says that by the 18th and 19th century, Spain had practically lost the favor of the colonies already and the Napoleonic Wars were the perfect trigger for freedom, even here with a stronger army, I don't see the Spaniards managing to overcome Bolivar or hold New Spain, especially that since with the still wrecking of their capital and several other cities, they will be lacking the funds as well, not to mention Brazil-Portugal wanting to expand into the Plata region and take over the place, Spain has too few men to defend and hold their overextended empire in the Americas.

Last edited:

Which is not a word I'd use to describe Ferdinand VII.had the Bourbon Kings been more competent.

Ferdinand VII isn't exactly a competent monarch not to mention Spain can't exactly afford to go around fighting in the Americas given how much wrecked Spain has becomeHowever, this post by Meordal also details how Spain might keep her colonies, had the Bourbon Kings been more competent.

That's more likely.Is Napoleon hoping Russia will save him? Lmao

On the other hand, Murat the snake......

I must say that i like the course with which war is going and the fact that Alex potentially won't backstab his Sister (even because of self interest).

That would have quite an impact on Danish/Russian relations in the long run as in otl Russia kinda sold them out. Who knows depending on how things play out Denmark might keep it's union with Norway.

Honestly they might get their otl borders in the west with otl Congress Poland depending on how things play out. But it's also quite likely that Austria/Prussia prevail with Russia just getting Finland.

Add rest of the Austrian Empire to the south as Habsburgs aren't letting go of their Empire, then there's whole Polish partition and how it will play out.

But honestly i expect Prussia expanding further North will face some hardships given that Hannover is still in union with the British (but depending how things play out they might give it up in exchange for Indonesia).

What i would find likely to happen is Austria getting Bavaria in exchange for Prussia getting whole of Saxony in order to complete their hegemony of Germany , punish the traitors and beef both states up in face of France and Russia and rest of Germany going more , or less similar path with German Confederation (minus the Rhine) with now enlarged German states on the west serving as a buffer between Austria/Prussia and France .

I would actually Iike that development as well, since it would be an inversion of OTL circumstances and net everyones assumption of Russia getting Finland like OTL.

That would have quite an impact on Danish/Russian relations in the long run as in otl Russia kinda sold them out. Who knows depending on how things play out Denmark might keep it's union with Norway.

Napoleon is a very prideful guy as well as I'm thinking Russia will bail him out, which I think they will simply so they can get Finland and parts of Austria and Prussia as well as keep a strong France as bulwark against them and Britain, not only that, he still has troops to call upon and he's in enemy territory instead of being boxed into his nation land's like OTL, he definitely thinks he can somehow turn this around

Honestly they might get their otl borders in the west with otl Congress Poland depending on how things play out. But it's also quite likely that Austria/Prussia prevail with Russia just getting Finland.

It could be interesting, North Ruled Prussia and South ruled Austria?

Add rest of the Austrian Empire to the south as Habsburgs aren't letting go of their Empire, then there's whole Polish partition and how it will play out.

But honestly i expect Prussia expanding further North will face some hardships given that Hannover is still in union with the British (but depending how things play out they might give it up in exchange for Indonesia).

What i would find likely to happen is Austria getting Bavaria in exchange for Prussia getting whole of Saxony in order to complete their hegemony of Germany , punish the traitors and beef both states up in face of France and Russia and rest of Germany going more , or less similar path with German Confederation (minus the Rhine) with now enlarged German states on the west serving as a buffer between Austria/Prussia and France .

im a bit confused, Napoleon rejects the frankfurt proposals right? But still keeps the german lands west of the rhine?

Who knows?But still keeps the german lands west of the rhine?

sorry no im confused i thought was confirmed thats what alot my questions were assuming because france kept the natural borders.Who knows?

A common mistake, wait till canon events happensorry no im confused i thought was confirmed thats what alot my questions were assuming because france kept the natural borders.

The only thing confirmed for now is that there'll be a congress in Frankfurt, along with the terms that involve the Ottomans.sorry no im confused i thought was confirmed thats what alot my questions were assuming because france kept the natural borders.

random question did this also map out ottoman Caucasus borders? Like i know some parts of the black sea coast are ottoman, but it was a mess down there.The only thing confirmed for now is that there'll be a congress in Frankfurt, along with the terms that involve the Ottomans.

For the sake of convenience, the Ottomans control western Georgia (Poti, Akhaltsikhe, Akhalkalaki), while Russia controls the north. From what I know it's not 100% accurate (AFAIK Anapa was Ottoman territory until the 1820s or so), but 19th century borders are complicated enough as it is.random question did this also map out ottoman Caucasus borders? Like i know some parts of the black sea coast are ottoman, but it was a mess down there.

Part 12: One Final Effort

------------------

Part 12: One Final Effort

Napoleon's refusal of Metternich's terms, which were easily the best peace he could get given the circumstances he was in, came as a shock to most of Europe and his subjects. The French Empire was on the retreat everywhere: its client states in Italy and Germany were either nonexistent or at war against their former overlord, while Spain went from an ally of questionable usefulness to an outright enemy, one whose fight for freedom led to the death of countless irreplaceable veterans of the Grande Armée, along with one of his best marshals. The beliefs of Talleyrand and other secret (and not-so-secret) enemies of the emperor were vindicated - he was clearly beyond reason, and Europe wouldn't be at peace until he was removed from the picture for good, and that meant marching into Paris itself.

Still, despite their determination to end the War of the Fifth Coalition once and for all, it took months for the allies to begin their invasion of France. Their own armies had suffered terribly, to say nothing of the horrors their civilian populations went through, and the arrival of winter wreaked havoc on their logistics. While Napoleon used this respite to call up whatever conscripts he could still get his hands on, his wife, empress consort Catherine Pavlovna, wrote a flurry of letters to tsar Alexander I, pleading for her brother to intervene in the war, if not for Napoleon's sake, then for her young son, born on November 18 1809 (1). Though the Russian emperor's love of his sister (who was known among her family members as "Katya", a nickname that would also be used by her in-laws) is well known and documented, his commitment to stay neutral was as adamant as ever (2).

"Your husband rejected peace every time it was offered to him," one of his replies said. "Only he can stop this war."

Napoleon was alone.

Part 12: One Final Effort

Napoleon's refusal of Metternich's terms, which were easily the best peace he could get given the circumstances he was in, came as a shock to most of Europe and his subjects. The French Empire was on the retreat everywhere: its client states in Italy and Germany were either nonexistent or at war against their former overlord, while Spain went from an ally of questionable usefulness to an outright enemy, one whose fight for freedom led to the death of countless irreplaceable veterans of the Grande Armée, along with one of his best marshals. The beliefs of Talleyrand and other secret (and not-so-secret) enemies of the emperor were vindicated - he was clearly beyond reason, and Europe wouldn't be at peace until he was removed from the picture for good, and that meant marching into Paris itself.

Still, despite their determination to end the War of the Fifth Coalition once and for all, it took months for the allies to begin their invasion of France. Their own armies had suffered terribly, to say nothing of the horrors their civilian populations went through, and the arrival of winter wreaked havoc on their logistics. While Napoleon used this respite to call up whatever conscripts he could still get his hands on, his wife, empress consort Catherine Pavlovna, wrote a flurry of letters to tsar Alexander I, pleading for her brother to intervene in the war, if not for Napoleon's sake, then for her young son, born on November 18 1809 (1). Though the Russian emperor's love of his sister (who was known among her family members as "Katya", a nickname that would also be used by her in-laws) is well known and documented, his commitment to stay neutral was as adamant as ever (2).

"Your husband rejected peace every time it was offered to him," one of his replies said. "Only he can stop this war."

Napoleon was alone.

Napoleon and his marshals during their last campaign.

One January 2 1811, three months after the Battle of Lützen, two Coalition armies, numbering a whooping 350.000 men in total (120.000 Prussians and Swedes were led by Gebhard von Blücher, while the remaining 230.000 Austrians and Turks were led by Archduke Charles), crossed the Rhine at Mayence and Strasbourg. Hopelessly outnumbered, the French forces before them could only fall back, and so the main obstacle to allies' advance was logistics: with winter in full swing, France's countryside was full of snow, while its roads were reduced to rivers of mud. Because of this, it took the Coalition one entire month to reach Champagne, the flat region east of Paris, where the war's outcome would be decided.

With only 150.000 men (many of whom being teenagers who barely knew how to use their muskets) to face the behemoth lumbering its way to his capital, and hearing news the allies were dispersed after their grueling march, Napoleon struck first, engaging a Prussian corps at Brienne, the town where he began his military studies, on January 29 (3). Though he was victorious in the battle that ensued, the emperor was unable to score a decisive blow, and he was forced to retreat after the Coalition concentrated its troops and defeated his now outnumbered army at La Rothière three days later. Believing their enemy would fall back to Paris, Blücher and Charles agreed to converge upon the French capital from different directions - the former would march north, along the Marne river, while the latter would follow the Seine. This strategy would also reduce the strain on their logistics, which were nothing short of atrocious.

Napoleon, who could not ignore the golden opportunity the allied strategy presented to him, halted his retreat as soon as he heard of it. Not only were the two Coalition armies far away from each other, but they were marching at different speeds: Blücher, an aggressive gambler by nature, rushed forward, stringing his army out in the process, while Charles was more worried with keeping his forces concentrated and ready for battle, an approach that reduced his progress to a crawl. Leaving two corps behind to delay the Austrian advance as much as possible, the French emperor swung north.

The campaign that ensued was perhaps the most shocking of all the Napoleonic Wars. Though exhausted, hungry and full of conscripts, the Grande Armée advanced like lightning through the snow and mud, pouncing upon a small Prussian corps of 5.000 troops and destroying it at Champaubert, on February 10 1811. The French then turned west and engaged a larger force at Montmirail, putting it to flight as Prussian commander Ludwig von Yorck realized he was facing a much stronger foe than anticipated. He and his 37.000 men made a dash for Château-Thierry, whose bridge over the Marne was their last hope of escape, but a corps commanded by marshal Jacques Macdonald got there first. After a brief but desperate fight, Yorck was forced to surrender (4).

The Battle of Montmirail.

Caught off guard by the speed and suddenness of Napoleon's attacks, Blücher attempted to retake the initiative by attacking newly made marshal Marmont's isolated corps, left behind to keep an eye on his movements while the emperor chased Yorck to Château-Thierry, at Vauchamps. This was precisely what Napoleon wanted him to do, and so he marched to his marshal's aid in a bid to finish off what was left of the Prussian army. Blücher attempted to disengage before it was too late, but his retreat was a disaster - Marmont's pursuit was implacable, and whatever semblance of order the Prussian ranks still had vanished when Blücher, who was in the thick of the action to boost his men's morale, was captured by French cuirassiers (5).

The Six Days' Campaign, as this string of victories became known, threw the Coalition's plan to end the war out of the window - the Prussian forces on French soil weren't just neutralized or decapitated, they had virtually ceased to exist. Charles, whose army of 230.000 men was just a few dozen kilometers away from Paris at this point, ordered an immediate retreat, before the Grande Armée cut his lines of communication. Though they still had a considerable advantage in numbers, the allied soldiers' morale, already sapped by the sluggish pace of their march, sank like a rock: the ghost of Austerlitz and Jena was back, right when it seemed the French Empire, and the Revolution it embodied, was on the brink of destruction.

Not wanting the man who defeated him at Wagram, Osterhofen and Lützen to withdraw in good order for obvious reasons, Napoleon gave his men little time to rest before ordering them to march east, to cut the last allied army's lines of communication to Vienna and sow as much chaos in their ranks as possible (6). The sheer size of Charles' army became a drawback, with muddy roads already packed with supply wagons jamming as Austrian and Ottoman soldiers traveled through those same roads in their retreat. The archduke planned to fall back to Nancy and either force a decisive battle there or wait until the British, Spanish and Neapolitans invaded the south, which would force the French to stretch their already meager forces even further.

But Napoleon's troops reached Nancy first, their smaller numbers and knowledge of the best paths to take making them far more nimble than the lumbering beast that the allied army turned into. By late February, it seemed all hell was about to break loose: the French peasantry, largely apathetic and wanting peace at almost any price before the Six Days' Campaign, was becoming increasingly hostile to the invaders, who often stole everything they had in their desperation to stay warm and fed, forming small bands that, while not as formidable as the guerrillas that terrorized the Grande Armée in Spain, were yet another factor the Coalition forces had to worry about, to say nothing of the hit-and-run attacks staged by small French corps against their vanguard and rear.

Thus, by the time Archduke Charles finally came within sight of Nancy, on March 1, the number of soldiers he could count on had been whittled down to 190.000 men, which, while still a formidable force on paper, was now more interested in survival than anything else. To prevent the allies' escape, Napoleon concentrated all his available forces (themselves worn down to some 130.000 fighting troops) and dug in. His plan, a stark departure from the aggressive tactics he was accustomed to, was to force the allies to hurl themselves against his fortifications (located on the right bank of the river Meurthe) until they were exhausted, then take advantage of it.

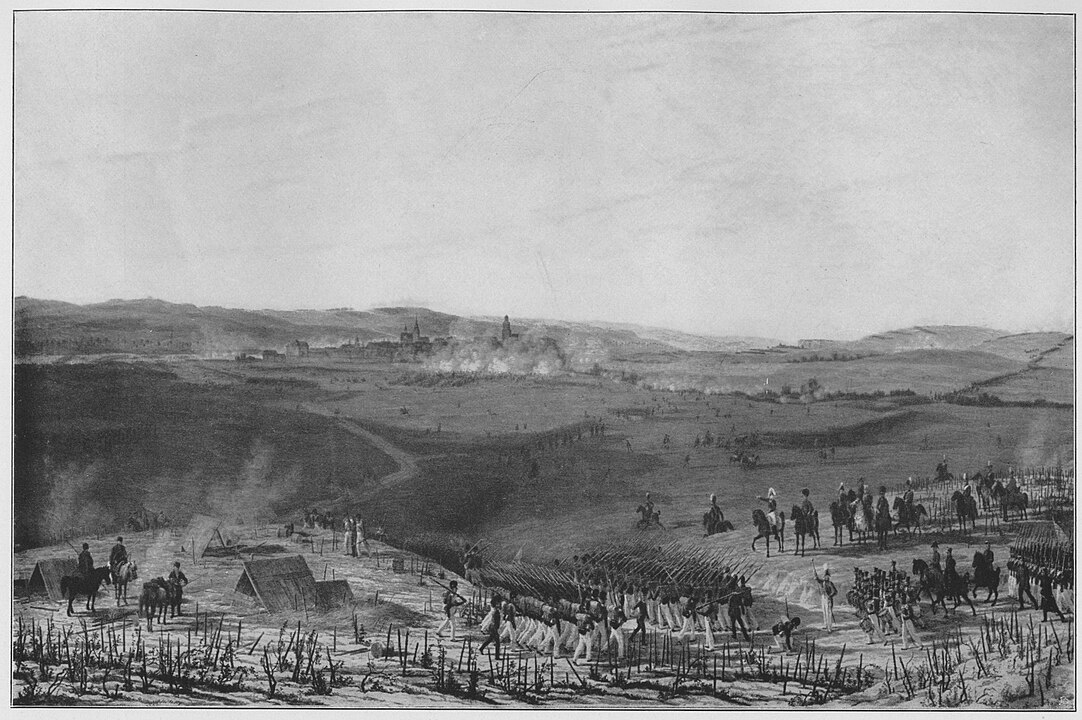

The Battle of Nancy, as seen from the allied camp.

If Lützen illustrated how the French army and that of the Fifth Coalition performed at their best, the Battle of Nancy, fought on March 2 1811, displayed how they were at their most desperate. Exhausted and starved after what felt like an eternity of marching and fighting, the rank and file of both sides wanted nothing more than an end to the fighting, a sentiment reflected in the addresses Charles and Napoleon gave to their troops shortly before the clash began: both promised this would be the last battle they would have to fight.

The Battle of Nancy began, as usual, with an artillery duel, which was where the allies' numerical advantage was most prominent: they had more than twice as many cannons as the French, even if their heaviest pieces had to be left behind in the mud. It didn't take long for a gap to appear in the French line thanks to the Austrian batteries' incessant bombardment, and Charles ordered his infantry forward as soon as he took notice of it. It was then, at that very moment, that the toll taken by the hunger and fatigue which hounded the Coalition soldiers since their retreat from Champagne became most apparent, as several collapsed after running a few dozen meters or less, while others, pushed by the belief that salvation was just beyond the enemy lines, rushed ahead randomly, blinded by the smoke created by the artillery duel.

What was supposed to be a charge devolved into a mob, and the allied attack was torn apart by French musket and cannon fire, the few men who reached the enemy earthworks easily repulsed. Some of Napoleon's more impetuous commanders argued this was the perfect time for a counterattack, but he refused to order one - his own troops were in shambles, and it is said he himself had to man a cannon at one point in the battle (7). The French sat behind their trenches and redoubts, waiting for the next allied attack.

This approach gave Charles plenty of time to plan his next move, and the offensive that ensued was far better organized than the first. The allied musketeers and grenadiers advanced under the cover of their artillery, and they soon reached the French earthworks in large numbers. Fierce hand to hand combat followed, as the combatants used bayonets, swords and musket butts to either fight their way into the enemy defenses (in the allies' case) or drive them out. This was a fight in which attrition would win the day, and Charles had far more men to spare for the meatgrinder than Napoleon did. The Coalition slowly pushed the French out of their earthworks, if at a terrible cost, as the hours went by, and this only emboldened their troops, desperate as they were to find a place where they could rest and eat safely.

Then a stray cannonball hit the allied gunpowder magazine, and the explosion it caused was so large and powerful even the men in the trenches could see, hear and feel it. Panic spread among the Coalition troops as rumors spread that Charles and their other commanders were dead, or, worse, what few supplies they had left turned to ash. Even so, the French were so worn down and bloodied at this point that they only managed to fight their enemies to a standstill, rather than push them out of their redoubts completely.

Fighting subsided with the arrival of nightfall. While the soldiers of both sides took what little sleep they could, their respective commanders debated furiously on what to do when the sun rose again. Charles' nerve was thouroughly broken by this point, and he was supposedly willing to accept almost any terms Napoleon offered him. The French emperor and his marshals, unaware of his plight, were divided between those who wanted to fight one more day and those who argued for an orderly withdrawal, fearing another day's fighting would shatter what little was left of the Grande Armée for good.

The Battle of Nancy began, as usual, with an artillery duel, which was where the allies' numerical advantage was most prominent: they had more than twice as many cannons as the French, even if their heaviest pieces had to be left behind in the mud. It didn't take long for a gap to appear in the French line thanks to the Austrian batteries' incessant bombardment, and Charles ordered his infantry forward as soon as he took notice of it. It was then, at that very moment, that the toll taken by the hunger and fatigue which hounded the Coalition soldiers since their retreat from Champagne became most apparent, as several collapsed after running a few dozen meters or less, while others, pushed by the belief that salvation was just beyond the enemy lines, rushed ahead randomly, blinded by the smoke created by the artillery duel.

What was supposed to be a charge devolved into a mob, and the allied attack was torn apart by French musket and cannon fire, the few men who reached the enemy earthworks easily repulsed. Some of Napoleon's more impetuous commanders argued this was the perfect time for a counterattack, but he refused to order one - his own troops were in shambles, and it is said he himself had to man a cannon at one point in the battle (7). The French sat behind their trenches and redoubts, waiting for the next allied attack.

This approach gave Charles plenty of time to plan his next move, and the offensive that ensued was far better organized than the first. The allied musketeers and grenadiers advanced under the cover of their artillery, and they soon reached the French earthworks in large numbers. Fierce hand to hand combat followed, as the combatants used bayonets, swords and musket butts to either fight their way into the enemy defenses (in the allies' case) or drive them out. This was a fight in which attrition would win the day, and Charles had far more men to spare for the meatgrinder than Napoleon did. The Coalition slowly pushed the French out of their earthworks, if at a terrible cost, as the hours went by, and this only emboldened their troops, desperate as they were to find a place where they could rest and eat safely.

Then a stray cannonball hit the allied gunpowder magazine, and the explosion it caused was so large and powerful even the men in the trenches could see, hear and feel it. Panic spread among the Coalition troops as rumors spread that Charles and their other commanders were dead, or, worse, what few supplies they had left turned to ash. Even so, the French were so worn down and bloodied at this point that they only managed to fight their enemies to a standstill, rather than push them out of their redoubts completely.

Fighting subsided with the arrival of nightfall. While the soldiers of both sides took what little sleep they could, their respective commanders debated furiously on what to do when the sun rose again. Charles' nerve was thouroughly broken by this point, and he was supposedly willing to accept almost any terms Napoleon offered him. The French emperor and his marshals, unaware of his plight, were divided between those who wanted to fight one more day and those who argued for an orderly withdrawal, fearing another day's fighting would shatter what little was left of the Grande Armée for good.

Cold, hungry and typhus-stricken French soldiers after the Battle of Nancy.

The latter party won out, and when the surviving Coalition soldiers woke up on the dawn of March 3, they were greeted by the sight of their enemies marching away from the battlefield, their banners vanishing over the horizon. Spontaneous celebrations broke out, and they intensified once the troops got word that Charles intended to abandon France altogether. Whether the archduke actually wanted this to happen is, utlimately, irrelevant - had he ordered his men to stay, it's probable they would've replied with a mutiny. The allied army, worn down to "just" 150.000 men in fighting shape after the horrors of Nancy, continued its retreat east, not stopping until it reached Kehl, on the German side of the Rhine.

But even while the people of Paris shouted Vive l'Empereur with a fervor unseen since Napoleon's coronation more than seven years before, the emperor himself had little reason to celebrate. His army was in no shape to take the war back to German soil, and because of this it was only a matter of time before Charles invaded France a second time, with an army larger and better supplied than anything Napoleon could hope to match.

The news coming from the south were even worse, as Joachim Murat finally launched his long-awaited assault on Nice, whose defenders, demoralized after the defeats suffered by Eugène de Beauharnais in Italy, surrendered after only a short bombardment. The Rhône valley was now wide open to an Austro-Neapolitan attack, and as if that wasn't enough, French agents in the Pyrenees issued reports stating the British and Spanish were ready to go on the offensive once more, having recovered from the defeats suffered at the hands of then general Marmont last September.

Napoleon's back was still against the wall, but his star recovered some of it's prior shine - he inflicted upon the Austrians their worst defeat since Austerlitz, while Prussia was no longer a factor to worry about. Still, his position would only get worse if he kept fighting, and he knew it: all he wanted now was to keep his throne, and spend the rest of his life with his son and the wife he learned to love so much (8).

And so it was that the man who spent most of his adulthood at war finally sued for peace.

------------------

Note:

(1) Needless to say, this isn't OTL's Nappy II.

(2) Alexander doesn't take this stance just because of spite against Napoleon, but also because of his need to focus on Russia's domestic affairs after its defeat at the hands of the Ottomans.

(3) When the Sixth Coalition invaded northern France in 1814, Napoleon had only 70.000 men to counter them IOTL. I think it's plausible for him to have a few more dozen thousand troops available ITTL, since there's no invasion of Russia.

(4) During the OTL Six Days' Campaign, Yorck and Russian commander Osten-Sacken only barely managed to escape Napoleon's grasp.

(5) According to the Wikipedia article on Vauchamps, Blücher was almost captured during the retreat.

(6) Napoleon tried to pull off this strategy IOTL, after he failed to score a decisive victory against Blücher or Schwarzenberg. Unfortunately for him, the allies got word of the shambolic state of Paris' defenses through a captured courier, and they rushed into the French capital.

(7) This supposedly happened IOTL, during the Battle of Montereau.

(8) Napoleon had a good relationship with Marie Louise even though she was a Habsburg (and thus a relative of Marie Antoinette), so it's only fair he gets along with Katya as well.

God you're just delivering with these chapters, you really managed to write well what a great military commander Napoleon was but without making him some genius who's plans seems like magic, just little factors of him using terrain and knowledge about the land to eventually wreck his enemies.

Most important of all, he didn't win the war but he will certainly win the peace, especially after a victory like that and while Russia can't help on the actual battlefield, the diplomacy table has no such limitations on help...

Most important of all, he didn't win the war but he will certainly win the peace, especially after a victory like that and while Russia can't help on the actual battlefield, the diplomacy table has no such limitations on help...

Wonderfully written, this war was full of twist and turns that made it unpredictability excellent .

But well Napoleon is finally faced with reality and is humbled after being brought from the heights of his rein, yet again his last show of persistence clearly paid of and brought him on last victory, how he plays it remains to be seen.

Coalition after this will probably be willing to give him anything he wants as long as his terms are at least reasonable. It's quite likely that France gets to keep Empire proper minus maybe Ilyrian provinces/Dalmatia that will go to Austria/Ottomans and potentially give up Rome as well.

Then there's state of Coalition, Prussia was made non factor and honestly at this point with its Army still intact Austria has a wonderful chance to gain preeminence in Germany as long as it avoids another war, by this point Austria might just decide to go in it alone and take Bavaria for itself while giving Prussia its pre-war borders but no new land in Germany.

I also like Alex's response to all of this, guy had wisened up and decided to be neutral, he honored his alliance with Napoleon via his Sister but he also knew that it's useless to get involved as long as Napoleon doesn't plan for a long-term peace. Honestly in this new climate Ottomans might get some kind of deal with Russia without another war.

British depending on the outcome will be seething with anger as France still has strength to fight, yet both it and Europe are tired, but depending how peace goes they might as well keep all Dutch colonies.

These are just guesses, I'm not sure myself how peace will turn out, well besides it going a little bit in French favor if we base it of on Frankfurt proposal.

But well Napoleon is finally faced with reality and is humbled after being brought from the heights of his rein, yet again his last show of persistence clearly paid of and brought him on last victory, how he plays it remains to be seen.

Coalition after this will probably be willing to give him anything he wants as long as his terms are at least reasonable. It's quite likely that France gets to keep Empire proper minus maybe Ilyrian provinces/Dalmatia that will go to Austria/Ottomans and potentially give up Rome as well.

Then there's state of Coalition, Prussia was made non factor and honestly at this point with its Army still intact Austria has a wonderful chance to gain preeminence in Germany as long as it avoids another war, by this point Austria might just decide to go in it alone and take Bavaria for itself while giving Prussia its pre-war borders but no new land in Germany.

I also like Alex's response to all of this, guy had wisened up and decided to be neutral, he honored his alliance with Napoleon via his Sister but he also knew that it's useless to get involved as long as Napoleon doesn't plan for a long-term peace. Honestly in this new climate Ottomans might get some kind of deal with Russia without another war.

British depending on the outcome will be seething with anger as France still has strength to fight, yet both it and Europe are tired, but depending how peace goes they might as well keep all Dutch colonies.

These are just guesses, I'm not sure myself how peace will turn out, well besides it going a little bit in French favor if we base it of on Frankfurt proposal.

Last edited:

I feel like an idiot for not realizing you are basing chapter developments based on subverting our discussion.

Am I wrong?

Am I wrong?

Threadmarks

View all 20 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 13: The Congress of Frankfurt Part 14: The Spectre of Revolution Part 15: Papers and Muskets Map: Europe after the Congress of Frankfurt Part 16: Carrots, Sticks and Daggers Part 17: A Beacon of Hope and Fear Part 18: An Eagle Reborn Part 19: Death of an Empire, (Re) Birth of Another

Share: